From the unfathomable singularity of the Big Bang to the vast, intricate cosmic web of galaxies and planets we observe today, the universe has undergone a remarkable journey spanning 13.8 billion years. This article delves into the comprehensive history and anatomy of our universe, exploring its origin, evolution through various epochs, the formation and structure of galaxies, and the ubiquitous presence of planets.

The Genesis: From Singularity to Expansion

The prevailing scientific model for the origin and evolution of the universe is the Big Bang theory. This theory posits that the universe began approximately 13.8 billion years ago from an extremely hot, dense state, a singularity, and has been continuously expanding and cooling ever since. The initial moments after the Big Bang were characterized by extreme conditions and rapid transformations, laying the groundwork for all subsequent cosmic development.

The Planck Epoch (t < 10^-43 seconds)

The earliest conceivable period in the universe’s history is the Planck epoch, lasting from time zero to approximately 10^-43 seconds. During this infinitesimally brief interval, the universe was incredibly hot and dense, and all four fundamental forces of nature—gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force—are believed to have been unified into a single, super force. Our current understanding of physics, particularly quantum mechanics and general relativity, breaks down at this scale, making it a realm of theoretical speculation. It is thought that quantum effects of gravity dominated physical interactions during this epoch.

The Grand Unification Epoch (10^-43 to 10^-36 seconds)

As the universe expanded and cooled, gravity is thought to have separated from the other unified forces. The remaining three forces—the strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces—remained unified in what is known as the Grand Unified Theory (GUT) force. The universe continued its rapid expansion and cooling during this phase.

The Inflationary Epoch (10^-36 to 10^-32 seconds)

One of the most significant events in the early universe was cosmic inflation, an incredibly rapid, exponential expansion of space. This period, lasting from approximately 10^-36 to 10^-32 seconds, saw the universe expand by a factor of at least 10^26. Inflation elegantly explains several perplexing features of the universe, including its observed flatness, homogeneity on large scales, and the absence of magnetic monopoles. The immense energy driving inflation was subsequently converted into a hot, dense plasma of particles, effectively reheating the universe and setting the stage for subsequent particle formation.

The Electroweak Epoch (10^-32 to 10^-12 seconds)

Following inflation, the universe continued to cool, and the strong nuclear force separated from the electroweak force. During this epoch, the universe was a hot, dense soup of fundamental particles, including quarks, leptons, and their antiparticles, constantly interacting. The electroweak force itself would later split into the distinct electromagnetic and weak forces.

The Quark Epoch (10^-12 to 10^-5 seconds)

As the universe cooled further, from 10^-12 to 10^-5 seconds, the temperature dropped sufficiently for quarks and antiquarks to begin forming hadrons, such as protons and neutrons. However, the energy was still too high for these hadrons to form stable atomic nuclei. A crucial event during this epoch was baryogenesis, a slight asymmetry between matter and antimatter that resulted in a tiny excess of matter. This minuscule imbalance is responsible for all the matter we observe in the universe today, as most matter-antimatter pairs annihilated each other.

The Hadron and Lepton Epochs (10^-5 seconds to 10 seconds)

In the hadron epoch (10^-5 seconds to 1 second), most hadrons and anti-hadrons annihilated, leaving behind a small remnant of hadrons. This was followed by the lepton epoch (1 second to 10 seconds), where leptons and anti-leptons underwent similar annihilation, leaving a residue of leptons. During the lepton epoch, neutrinos decoupled from the rest of the matter, forming the cosmic neutrino background, a relic radiation similar to the CMB but composed of neutrinos.

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (3 minutes to 20 minutes)

Approximately 3 to 20 minutes after the Big Bang, the universe had cooled to a point where nuclear fusion could occur. Protons and neutrons fused to form the nuclei of light elements: deuterium (a heavy isotope of hydrogen), helium-3, helium-4, and trace amounts of lithium. This process, known as Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN), accurately predicts the observed cosmic abundances of these light elements, providing strong evidence for the Big Bang model.

The Photon Epoch (10 seconds to 380,000 years)

For the next 380,000 years, the universe was dominated by photons. The temperature was still too high for electrons to bind with atomic nuclei, so matter existed as a hot, ionized plasma. Photons constantly scattered off these free electrons, making the universe opaque to light. It was a fiery, glowing fog.

The Early Universe: From Darkness to Light

Recombination (380,000 years)

Around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe cooled to approximately 3,000 Kelvin. At this critical temperature, electrons finally combined with atomic nuclei to form stable, neutral atoms, primarily hydrogen and helium. This event is known as recombination. With the formation of neutral atoms, photons were no longer constantly scattered and could travel freely through space. This decoupling of photons from matter led to the formation of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation, a faint afterglow of the Big Bang that permeates the entire universe. The CMB is a crucial piece of evidence supporting the Big Bang theory, acting as a snapshot of the universe when it was just a baby.

The Dark Ages (380,000 years to 150 million years)

Following recombination, the universe entered a period known as the Dark Ages. During this time, the universe was filled with neutral hydrogen and helium gas, and there were no stars or galaxies to emit light. The only radiation present was the CMB. This period is considered “dark” because there were no luminous objects, and the universe was largely opaque to visible light.

First Stars and Reionization (150 million years to 1 billion years)

Around 150 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang, the first stars and quasars began to form. These pioneering luminous objects, much more massive and short-lived than our Sun, emitted intense ultraviolet radiation. This energetic radiation reionized the neutral hydrogen and helium gas in the universe, a process known as reionization. This made the universe transparent to ultraviolet light once again, marking the end of the Dark Ages and the dawn of the cosmic era of light. The formation of these first stars and galaxies initiated the cosmic cycle of star formation and chemical enrichment.

Gravity Builds Cosmic Structure: The Rise of Galaxies

Over billions of years, gravity, the persistent architect of the cosmos, amplified the tiny density fluctuations present in the early universe. Regions with slightly higher concentrations of matter began to attract more matter, leading to a runaway process of gravitational collapse. This hierarchical process resulted in the formation of increasingly larger structures, from the first stars to the grand galaxies and vast cosmic webs we observe today. Dark matter, an enigmatic substance that interacts only through gravity, played a pivotal role in this process, providing the gravitational scaffolding upon which visible matter could accumulate and form these structures.

Galaxy Formation and Evolution

Galaxies are the fundamental building blocks of the large-scale structure of the universe. They are colossal collections of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, and dark matter, all gravitationally bound. Their formation is a complex process that began shortly after the first stars ignited.

Early galaxies were likely smaller and more irregular, growing through a continuous process of accretion and mergers. Smaller galaxies collided and merged, forming larger and more complex structures. This process is still ongoing, with galaxy mergers being a common occurrence in the universe, often triggering bursts of star formation and reshaping galactic morphology.

Factors influencing galaxy evolution include:

•Mergers and Interactions: Galactic collisions are powerful events that can dramatically alter a galaxy’s structure, trigger intense star formation, and even lead to the formation of new, larger galaxies.

•Star Formation Rate: The rate at which new stars are born within a galaxy significantly impacts its appearance and chemical composition. Early galaxies were characterized by vigorous star formation, while many present-day galaxies exhibit more subdued rates.

•Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN): Supermassive black holes residing at the centers of most massive galaxies can accrete surrounding matter, releasing immense amounts of energy. This energy can influence star formation and gas dynamics within the host galaxy.

•Environmental Effects: The cosmic environment, such as being part of a dense galaxy cluster or an isolated field, can affect a galaxy’s evolution through gravitational interactions and the stripping away of gas.

Structure of Galaxies

Galaxies exhibit a diverse range of morphologies, broadly categorized into three main types:

•Spiral Galaxies: These are characterized by a flat, rotating disk containing spiral arms, a central bulge, and a surrounding halo. The spiral arms are regions of active star formation, rich in young, hot, blue stars, gas, and dust. The central bulge is a denser, more spherical region composed primarily of older stars. Our own Milky Way galaxy is a barred spiral galaxy.

•Elliptical Galaxies: These galaxies are typically smooth, featureless, and possess an elliptical shape, ranging from nearly spherical to highly elongated. They are generally composed of older stars and contain very little interstellar gas and dust, indicating minimal ongoing star formation. Elliptical galaxies are thought to form through the mergers of spiral galaxies.

•Irregular Galaxies: As their name suggests, these galaxies lack a distinct, regular shape and often appear chaotic. They are typically smaller than spiral or elliptical galaxies and are abundant in gas and dust, leading to vigorous and often patchy star formation. Irregularities can be a result of gravitational interactions with other galaxies.

Beyond these primary classifications, there are also lenticular galaxies, which represent an intermediate form between spirals and ellipticals, and dwarf galaxies, which are small, faint galaxies that are incredibly numerous throughout the universe.

Number of Galaxies in the Universe

Estimating the total number of galaxies in the universe is a monumental task, given the vastness of space and the limitations of our observational instruments. However, based on deep-field observations and statistical extrapolations, current estimates suggest an astonishing number:

•Hundreds of billions to trillions of galaxies in the observable universe. Early estimates often cited around 100 billion galaxies. However, more recent and comprehensive surveys, particularly those conducted by the Hubble Space Telescope, have led to revised estimates suggesting as many as 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe. This number is constantly being refined as new data becomes available and our understanding of the distant universe improves.

It is crucial to remember that these figures pertain to the observable universe—the portion of the universe from which light has had sufficient time to reach us since the Big Bang. The actual number of galaxies in the entire universe, which extends far beyond our current observational horizon, is undoubtedly much larger.

Planets: Cosmic Companions

Planets are ubiquitous celestial bodies that orbit stars, are massive enough to be rounded by their own gravity, and have cleared their orbital neighborhood of other debris. Their formation is an integral part of the star formation process, occurring within the swirling disks of gas and dust that surround young stars.

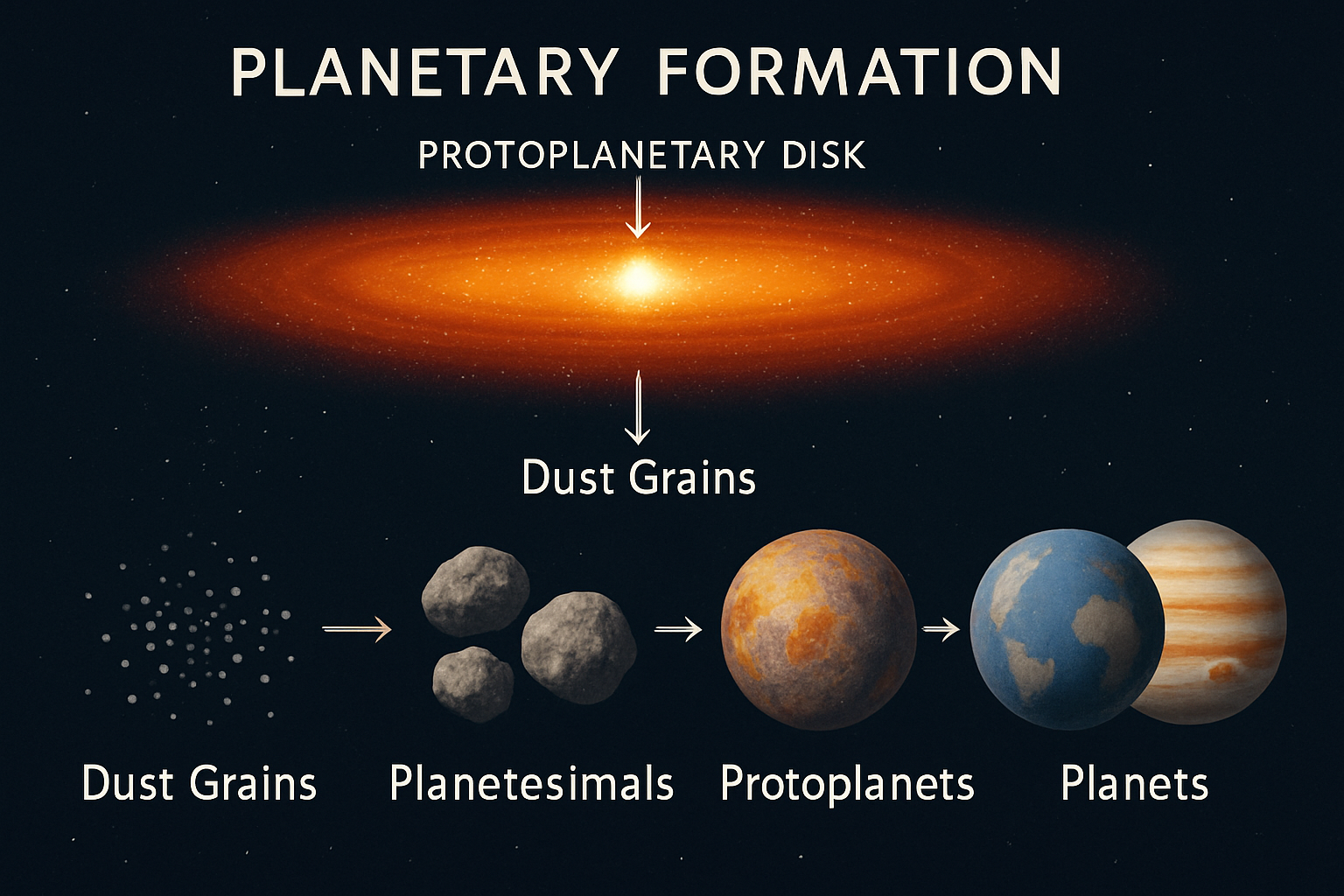

Planetary Formation

The most widely accepted model for planet formation is the core accretion model. This model describes a gradual process where planets grow from microscopic dust grains within a protoplanetary disk—a rotating disk of gas and dust surrounding a newly formed star. The process unfolds in several stages:

1.Dust Aggregation: Tiny dust particles in the protoplanetary disk collide and stick together due to electrostatic forces, forming larger aggregates.

2.Planetesimal Formation: As these aggregates grow, they reach sizes of a few kilometers, becoming planetesimals. At this stage, gravity begins to play a more significant role, pulling in more material.

3.Protoplanet Formation: Planetesimals continue to collide and merge, forming larger bodies known as protoplanets. These protoplanets are massive enough to gravitationally attract and sweep up surrounding debris in their orbital paths.

4.Gas Accretion (for Gas Giants): If a protoplanet reaches a critical mass (around 5-10 Earth masses) relatively quickly, before the surrounding gas in the protoplanetary disk dissipates, its strong gravity can rapidly accrete vast amounts of hydrogen and helium gas. This leads to the formation of gas giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn.

5.Terrestrial Planet Formation: For rocky, terrestrial planets like Earth, the process is slower. After the gas in the protoplanetary disk has largely dissipated, the remaining planetesimals and protoplanets continue to collide and merge over millions to tens of millions of years, gradually building up the rocky cores and mantles of these planets.

While core accretion is the dominant theory, another model, the gravitational instability model, suggests that gas giant planets can form directly from the rapid collapse of dense regions within the protoplanetary disk, bypassing the slower core accretion phase. This model is particularly relevant for very massive gas giants forming at large distances from their host stars.

Number of Planets in the Universe

The discovery of thousands of exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than our Sun) has profoundly changed our understanding of planetary abundance. It is now clear that planets are not rare but are, in fact, a common byproduct of star formation. While our solar system has eight major planets, the universe is teeming with countless others.

Based on current observations and statistical extrapolations, astronomers estimate that:

•Billions of planets exist in our Milky Way galaxy alone. Astronomical surveys indicate that most stars in our galaxy host at least one planet. Given that the Milky Way contains hundreds of billions of stars, this translates to hundreds of billions of planets within our home galaxy.

•Trillions of planets in the observable universe. Extending this logic to the entire observable universe, which contains trillions of galaxies, the total number of planets becomes truly staggering. Conservative estimates suggest there could be as many as 20 sextillion (2 x 10^22) planets in the observable universe. Other estimates vary, but all point to an immense number of planetary bodies.

These numbers are continually being refined as new exoplanets are discovered and our observational techniques improve. The sheer prevalence of planets underscores the potential for diverse planetary environments and the ongoing search for habitable worlds beyond Earth.

Be First to Comment