Introduction

Gravity, the most familiar yet enigmatic of the fundamental forces, orchestrates the

cosmos on scales ranging from the smallest particles to the grandest galaxy clusters. It

dictates the orbits of planets, the formation of stars, and the very structure of the

universe. Our understanding of gravity has evolved dramatically over centuries, from

Isaac Newton’s classical description of universal attraction to Albert Einstein’s

revolutionary theory of general relativity, which redefines gravity as the curvature of

spacetime itself. More recently, the direct detection of gravitational waves has opened

a new window into the most violent and energetic events in the cosmos, further

deepening our comprehension of this pervasive force.

This article delves into the anatomy of gravitational mechanisms, exploring its

fundamental principles, the mathematical frameworks that describe its behavior, and

the cutting-edge discoveries that continue to shape our understanding. We will

journey from the classical Newtonian view to the intricate geometry of Einstein’s

spacetime, and then venture into the exciting realm of gravitational wave astronomy

and the ongoing quest for a unified theory of quantum gravity. By examining these

facets, we aim to provide a comprehensive and profound insight into the force that

binds the universe together.

The Classical View: Newtonian Gravity

Before Einstein, Isaac Newton provided the first comprehensive theory of gravity in his

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (

). Newton’s law of universal

gravitation states that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a

force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely

proportional to the square of the distance between their centers [ ]. Mathematically,

this is expressed as:

F =G r2

mm1 2

F

G

Where: * is the gravitational force between the two objects. * is the gravitational

constant, approximately

−11

6.674 × 10 N⋅

r

(m/kg)2 m1

. *

and

m2

are the masses of

the two objects. * is the distance between the centers of the two masses.

Newton’s theory successfully explained a wide range of phenomena, including the

orbits of planets around the Sun, the trajectory of projectiles, and the occurrence of

tides. It provided a powerful framework for understanding the mechanics of the solar

system and laid the foundation for classical physics. Despite its remarkable success,

Newtonian gravity had limitations. It described how gravity acts but not why it acts. It

also struggled to explain certain subtle astronomical observations, such as the

anomalous precession of Mercury’s orbit, which would later be precisely accounted for

by Einstein’s theory.

Einstein’s Revolution: General Relativity and

Spacetime

Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, published in

, fundamentally

reshaped our understanding of gravity. Instead of a force acting between masses,

Einstein proposed that gravity is a manifestation of the curvature of spacetime caused

by the presence of mass and energy. Imagine a stretched rubber sheet: placing a heavy

ball on it causes the sheet to sag. If you then roll a smaller marble across the sheet, its

path will be deflected by the sag, not by a direct force from the heavy ball. Similarly,

massive objects like planets and stars warp the fabric of spacetime around them, and

other objects (including light) follow the curves in this warped spacetime, which we

perceive as gravity.

This revolutionary concept is encapsulated in Einstein’s field equations, which relate

the geometry of spacetime to the distribution of matter and energy within it:

G +

μν

Where: *

Λg =

μν T c4

8πG μν

Gμν

is the Einstein tensor, representing the curvature of spacetime. *

the metric tensor, defining the geometry of spacetime. *

gμν

Λ

is

is the cosmological

G

is Newton’s gravitational

c

constant, related to the expansion of the universe. *

constant. * is the speed of light. *

Tμν

distribution of matter and energy.

is the stress-energy tensor, representing the

General relativity has passed numerous rigorous tests, including the precise prediction

of the anomalous precession of Mercury’s orbit, the bending of light by massive

objects (gravitational lensing), and gravitational redshift. It also predicted the

existence of black holes, regions of spacetime where gravity is so strong that nothing,

not even light, can escape, and gravitational waves, ripples in spacetime caused by

accelerating massive objects [ ].

Gravitational Waves: Ripples in Spacetime

One of the most profound predictions of general relativity was the existence of

gravitational waves ‒ ripples in the fabric of spacetime that propagate at the speed of

light. These waves are generated by the acceleration of massive objects, much like

electromagnetic waves are generated by accelerating electric charges. However,

gravitational waves are incredibly weak and require immense cosmic events to

produce detectable signals.

The direct detection of gravitational waves was a monumental achievement in

physics, first accomplished by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave

Observatory (LIGO) in

[ ]. This groundbreaking discovery confirmed a century

old prediction of Einstein’s theory and opened a new era of gravitational-wave

astronomy. The first detected event, GW

, was caused by the merger of two

black holes, an event that released an extraordinary amount of energy in the form of

gravitational waves, equivalent to about three solar masses converted into pure

energy.

Gravitational wave detectors like LIGO and Virgo operate by using laser interferometry

to measure minute distortions in spacetime caused by passing gravitational waves.

These observatories consist of L-shaped vacuum arms, several kilometers long, with

mirrors at their ends. A laser beam is split and sent down each arm, reflected by the

mirrors, and recombined. In the absence of gravitational waves, the two beams arrive

back in phase. However, a passing gravitational wave will subtly stretch and squeeze

spacetime, causing a tiny difference in the length of the arms, which in turn causes the

laser beams to become slightly out of phase, creating an interference pattern that can

be detected.

The detection of gravitational waves has provided unprecedented insights into

extreme astrophysical phenomena, including black hole mergers, neutron star

collisions, and potentially, the very early universe. It allows us to ‘hear’ the universe in

a way that electromagnetic telescopes cannot, revealing events that are otherwise

invisible.

The Quest for Quantum Gravity

Despite the remarkable success of general relativity in describing gravity on

macroscopic scales, it is fundamentally incompatible with quantum mechanics, the

theory that governs the universe at its smallest scales. General relativity describes

gravity as a smooth, continuous curvature of spacetime, while quantum mechanics

describes other fundamental forces (electromagnetism, strong, and weak nuclear

forces) in terms of discrete packets of energy called quanta. This incompatibility poses

one of the most significant challenges in modern physics: the quest for a theory of

quantum gravity.

A successful theory of quantum gravity would unify all four fundamental forces of

nature into a single, coherent framework. Several theoretical approaches are being

explored to achieve this unification, including:

String Theory: This theory proposes that the fundamental constituents of the

universe are not point-like particles but tiny, one-dimensional vibrating strings.

Different vibrational modes of these strings correspond to different particles,

including the graviton, the hypothetical quantum of gravity.

Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG): LQG attempts to quantize spacetime itself,

suggesting that spacetime is not continuous but is made up of discrete loops.

This approach aims to describe gravity in a way that is consistent with quantum

mechanics without introducing extra dimensions or particles.

Other Approaches: Other theories include causal set theory, asymptotically safe

gravity, and non-commutative geometry, each offering a unique perspective on

how to reconcile gravity with quantum mechanics.

The development of a complete theory of quantum gravity is crucial for understanding

phenomena where both gravity and quantum effects are significant, such as the

singularity at the heart of black holes and the very beginning of the universe during

the Big Bang. While no definitive theory has emerged yet, the ongoing research in this

field promises to unlock deeper secrets of the cosmos.

Conclusion

From Newton’s apple to Einstein’s warped spacetime and the symphony of colliding

black holes, our understanding of gravity has undergone a profound transformation.

What began as a description of an attractive force has evolved into a sophisticated

geometric theory of spacetime, with implications that stretch across the cosmos. The

detection of gravitational waves has ushered in a new era of astronomical discovery,

allowing us to probe the universe’s most extreme events in unprecedented detail.

The ongoing pursuit of a quantum theory of gravity represents the next frontier in our

quest to comprehend the fundamental nature of reality. While the path to unification

remains challenging, the insights gained from these endeavors continue to push the

boundaries of human knowledge, revealing an ever more intricate and awe-inspiring

universe governed by the elegant dance of gravitational mechanisms, or rather, the

elegant curvature, of gravity.

The Anatomy and Deep Understanding of Gravitational Mechanisms in the Universe

More from UncategorizedMore posts in Uncategorized »

- The Human Safety Net: How 500+ Protective Measures Safeguard Animal Kingdom Survival

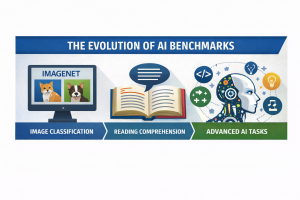

- Modern AI Industrial Benchmark Models:

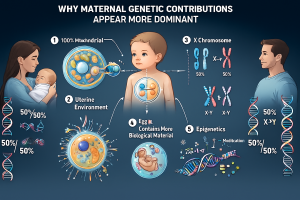

- Anatomy of the Reason for the Dominance of Female (Maternal) DNA in a Child

- Anatomy of Our Universe: An In‑Depth Thesis Article

- Uranium: The Hidden Engine of Modern Technology and Tomorrow’s World

Be First to Comment