Introduction

Trees stand as Earth’s most magnificent living monuments, silently shaping our planet’s climate, ecosystems, and human civilization for millions of years. These towering giants are far more complex and diverse than most people realize, with intricate anatomical systems that rival any engineering marvel. From the smallest bonsai to the tallest sequoia, trees represent one of nature’s most successful biological designs, having colonized nearly every habitat on Earth.

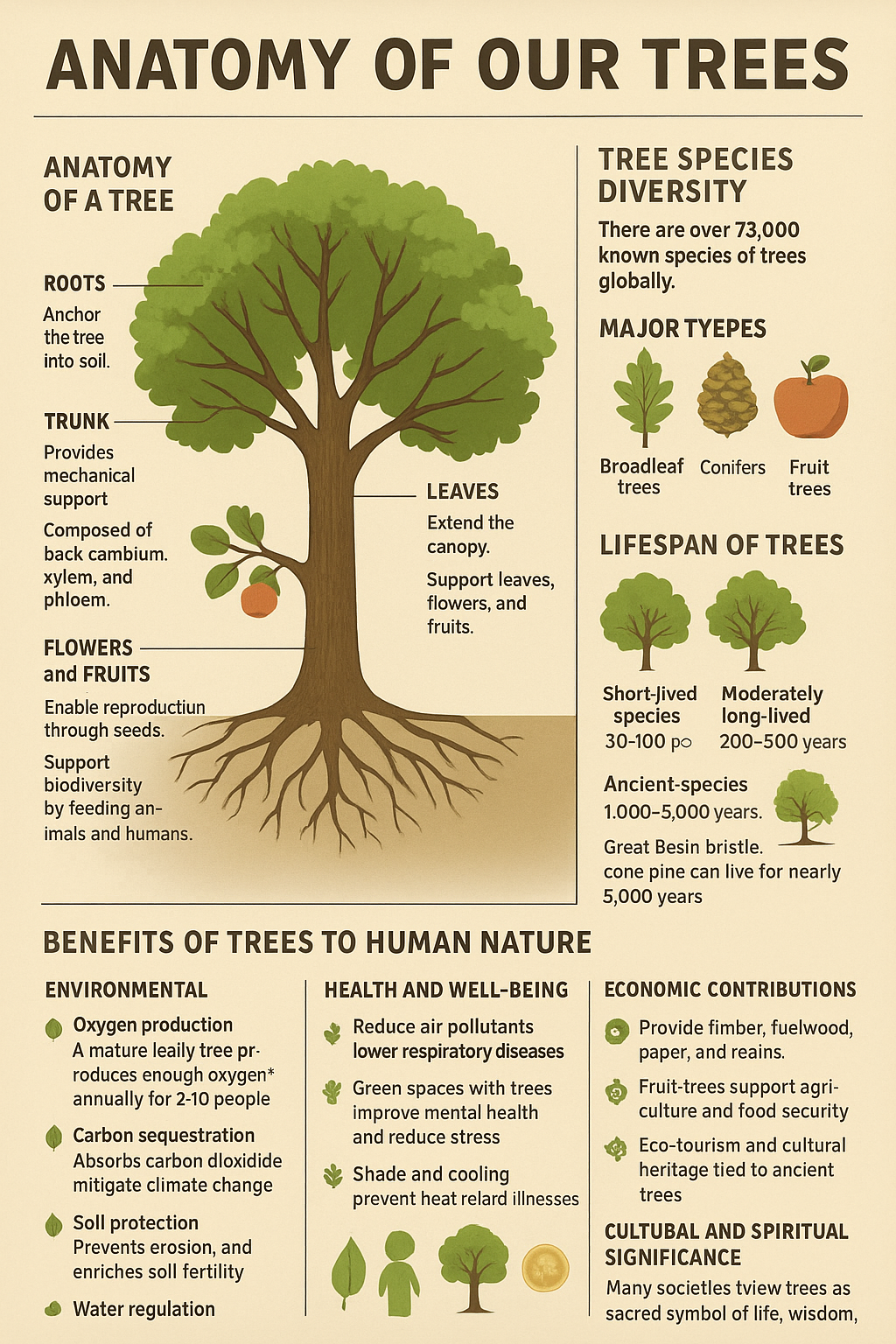

The Anatomy of Trees: Nature’s Architectural Masterpiece

Root System: The Hidden Foundation

The root system forms the tree’s invisible foundation, often extending far beyond the canopy’s reach. Contrary to popular belief, most tree roots spread horizontally rather than growing deep, typically occupying the top 18-24 inches of soil where oxygen and nutrients are most abundant.

Primary Components:

- Taproot: The main central root that anchors young trees and seeks deep water sources

- Lateral roots: Horizontal roots that spread outward, providing stability and nutrient absorption

- Feeder roots: Fine, hair-like roots responsible for water and nutrient uptake

- Root hairs: Microscopic extensions that dramatically increase the surface area for absorption

The root system serves multiple critical functions: anchoring the tree against wind and storms, absorbing water and dissolved minerals, storing energy reserves, and forming symbiotic relationships with beneficial fungi called mycorrhizae.

Trunk: The Tree’s Superhighway

The trunk serves as the tree’s central support structure and transportation system. Its complex anatomy consists of several distinct layers, each with specialized functions.

Anatomical Layers (from outside to inside):

- Bark (Outer and Inner)

- Outer bark: Dead, protective layer that shields against insects, disease, and fire

- Inner bark (Phloem): Living tissue that transports sugars from leaves to roots

- Cambium Layer

- A thin, microscopic layer of cells responsible for all trunk growth

- Produces new phloem outward and new xylem inward

- Active only during growing seasons

- Sapwood (Xylem)

- The “plumbing system” that transports water and minerals upward

- Consists of recently formed wood cells

- Typically lighter in color than heartwood

- Heartwood

- The tree’s structural backbone composed of dead xylem cells

- Often darker and denser than sapwood due to extractive deposits

- No longer transports fluids but provides mechanical support

Crown: The Tree’s Solar Panels and Food Factory

The crown encompasses all branches, twigs, and leaves above the trunk, forming the tree’s photosynthetic powerhouse.

Branch Architecture:

- Primary branches: Major limbs extending directly from the trunk

- Secondary branches: Smaller branches growing from primary branches

- Twigs: The youngest woody growth bearing leaves, flowers, and fruits

- Nodes: Points where leaves, branches, or reproductive structures emerge

- Internodes: Sections between nodes

Leaf Structure and Function: Leaves are sophisticated biological laboratories where photosynthesis occurs. Their anatomy includes:

- Epidermis: Protective outer layer with waxy cuticle

- Stomata: Microscopic pores that regulate gas exchange and water loss

- Mesophyll: Internal tissue containing chloroplasts for photosynthesis

- Vascular bundles: Veins that transport water, nutrients, and sugars

The Vascular System: Tree Transportation Network

Trees possess one of nature’s most efficient transportation systems, moving materials vertically over distances exceeding 300 feet in some species.

Xylem (Water Transport):

- Moves water and dissolved minerals from roots to leaves

- Functions through transpiration-driven negative pressure

- Can transport thousands of gallons daily in large trees

Phloem (Sugar Transport):

- Distributes photosynthetic products throughout the tree

- Operates through pressure-flow mechanism

- Supplies energy to non-photosynthetic tissues

Global Tree Diversity: A World of Species

The diversity of tree species worldwide is staggering and continues to surprise scientists. Recent research indicates there are approximately 73,000 tree species globally, among which roughly 9,000 tree species are yet to be discovered. This means our planet hosts far more tree diversity than previously imagined.

Species Distribution

Brazil leads the world in tree species count at 8,780, followed by other tropical regions that harbor the greatest diversity:

Top Tree Diversity Regions:

- South America: Home to nearly 40% of undiscovered species

- Southeast Asia: Particularly rich in tropical rainforest species

- Central Africa: Contains numerous endemic species

- Madagascar: Island isolation has created unique species

- Australia: Eucalyptus and Acacia species dominate

Conservation Concerns

Recent assessments reveal that more than one in three tree species worldwide faces extinction, highlighting the urgent need for conservation efforts. Climate change, deforestation, and habitat destruction pose significant threats to global tree diversity.

Major Tree Categories

Gymnosperms (Conifers)

- Include pines, firs, spruces, and cedars

- Characterized by needle-like leaves and cone reproduction

- Often evergreen and adapted to cooler climates

- Examples: Giant Sequoia, Douglas Fir, Eastern White Pine

Angiosperms (Flowering Trees)

- Broadleaf trees with flowers and fruits

- Divided into deciduous and evergreen species

- Display incredible diversity in form and function

- Examples: Oak, Maple, Cherry, Eucalyptus

Tree Lifespans: From Decades to Millennia

Tree lifespans vary dramatically across species, influenced by genetics, environmental conditions, and human activities.

Lifespan Categories

Short-lived Trees (10-50 years)

- Paper Birch: 20-40 years

- Quaking Aspen: 40-60 years

- Black Cherry: 20-30 years

- Many fruit trees: 15-50 years

Medium-lived Trees (50-200 years)

- Red Maple: 80-100 years

- White Pine: 100-200 years

- American Elm: 100-150 years

- Sugar Maple: 150-200 years

Long-lived Trees (200+ years)

- White Oak: 200-600 years

- Bald Cypress: 600-1,000 years

- Giant Sequoia: 1,500-3,000 years

- Bristlecone Pine: Up to 5,000 years

Record Holders

The oldest known living trees include:

- Methuselah (Bristlecone Pine): Over 4,800 years old

- The President (Giant Sequoia): Estimated 3,200 years old

- Jōmon Sugi (Japanese Cedar): 2,170-7,200 years old

Benefits to Human Nature: Trees as Life Partners

Trees provide an extraordinary range of benefits that are essential for human survival, health, and well-being. These benefits span environmental, economic, social, and health dimensions.

Environmental Benefits

Climate Regulation

- Carbon Sequestration: A mature tree absorbs 35-48 pounds of CO₂ annually

- Temperature Control: Trees can reduce local temperatures by 2-9°F through shade and evapotranspiration

- Humidity Regulation: Large trees release 100-400 gallons of water daily into the atmosphere

Air Quality Improvement

- Pollution Filtration: Trees remove harmful pollutants including ozone, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter

- Oxygen Production: One mature tree produces enough oxygen for two people per year

- Dust Reduction: Tree canopies intercept and trap airborne particles

Water Cycle Support

- Rainfall Enhancement: Forests increase local precipitation through evapotranspiration

- Erosion Prevention: Root systems stabilize soil and prevent erosion

- Water Filtration: Trees filter groundwater and reduce stormwater runoff

- Flood Control: Forest canopies intercept rainfall, reducing flood risks

Economic Benefits

Direct Economic Value

- Timber Industry: Provides materials for construction, furniture, and paper

- Food Production: Fruits, nuts, maple syrup, and other food products

- Medicine: Source of numerous pharmaceutical compounds

- Tourism: Forest tourism generates billions in revenue annually

Property Value Enhancement

- Well-landscaped properties with mature trees increase in value by 15-20%

- Trees reduce energy costs by providing natural cooling and windbreaks

- Strategic tree placement can reduce heating and cooling costs by 30%

Health and Social Benefits

Physical Health

- Air Quality: Improved air quality reduces respiratory diseases and cardiovascular problems

- Temperature Moderation: Reduced heat stress in urban environments

- Noise Reduction: Trees absorb sound pollution, creating quieter environments

- UV Protection: Tree canopies provide natural protection from harmful ultraviolet radiation

Mental Health and Well-being

- Stress Reduction: Exposure to trees and forests significantly reduces stress hormones

- Improved Mood: Forest environments boost serotonin levels and reduce anxiety

- Enhanced Creativity: Natural environments improve cognitive function and creativity

- Social Interaction: Tree-lined streets and parks encourage community gathering

Japanese Forest Bathing (Shinrin-yoku) Scientific research on forest bathing reveals measurable health benefits:

- Reduced cortisol levels

- Lowered blood pressure

- Boosted immune system function

- Improved sleep quality

Ecological Benefits

Biodiversity Support

- Single large oak trees can support over 500 species of insects

- Forests provide habitat for 80% of terrestrial biodiversity

- Trees create microhabitats and ecological niches

- Support complex food webs and ecosystem interactions

Soil Health

- Leaf litter creates rich organic matter

- Root systems improve soil structure and aeration

- Mycorrhizal associations enhance nutrient cycling

- Prevent soil compaction and degradation

Cultural and Spiritual Benefits

Cultural Significance

- Sacred groves and ceremonial trees in many cultures

- Symbol of growth, strength, and endurance

- Featured prominently in art, literature, and mythology

- Traditional knowledge and indigenous practices

Educational Value

- Living laboratories for scientific study

- Seasonal changes teach natural cycles

- Inspire environmental stewardship

- Connect people with natural processes

The Future of Trees and Humanity

As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, trees emerge as crucial allies in building sustainable futures. Climate change, urbanization, and biodiversity loss make tree conservation and restoration more important than ever.

Global Initiatives

- Reforestation projects aim to restore degraded landscapes

- Urban forestry programs increase city tree cover

- Agroforestry integrates trees with agriculture

- International cooperation addresses global forest conservation

Technology and Trees

- Satellite monitoring tracks forest health and deforestation

- Genetic research helps develop climate-resistant varieties

- Smart forestry uses data to optimize tree management

- Biotechnology explores new applications for tree products

Conclusion

Trees represent one of nature’s most sophisticated and beneficial creations. Their complex anatomy enables them to perform countless functions that sustain life on Earth. With approximately 73,000 species worldwide, trees display remarkable diversity in form, function, and lifespan. From short-lived pioneer species to ancient giants that have witnessed millennia of history, each tree contributes uniquely to our planet’s health.

The benefits trees provide to human nature are immeasurable, spanning environmental protection, economic value, health improvement, and spiritual enrichment. As we continue to understand the intricate relationships between trees and human well-being, it becomes increasingly clear that our futures are inextricably linked.

Protecting and expanding our tree resources is not just an environmental imperative but a fundamental requirement for human survival and prosperity. By appreciating the remarkable anatomy, celebrating the incredible diversity, and understanding the profound benefits of trees, we can foster a deeper connection with these silent guardians of our planet and work together to ensure they continue to thrive for generations to come.

Be First to Comment