Introduction

Atoms are the fundamental building blocks of all matter, the smallest unit of an element that retains the chemical identity of that element. Everything around us, from the air we breathe to the stars in the sky, is composed of atoms. The concept of the atom dates back to ancient Greek philosophers, but it wasn’t until the early 20th century that scientists began to truly understand its intricate structure. This article will delve into the comprehensive blocks of atoms, exploring their structure, the subatomic particles that constitute them, and their fundamental properties.

The Atomic Nucleus: Protons and Neutrons

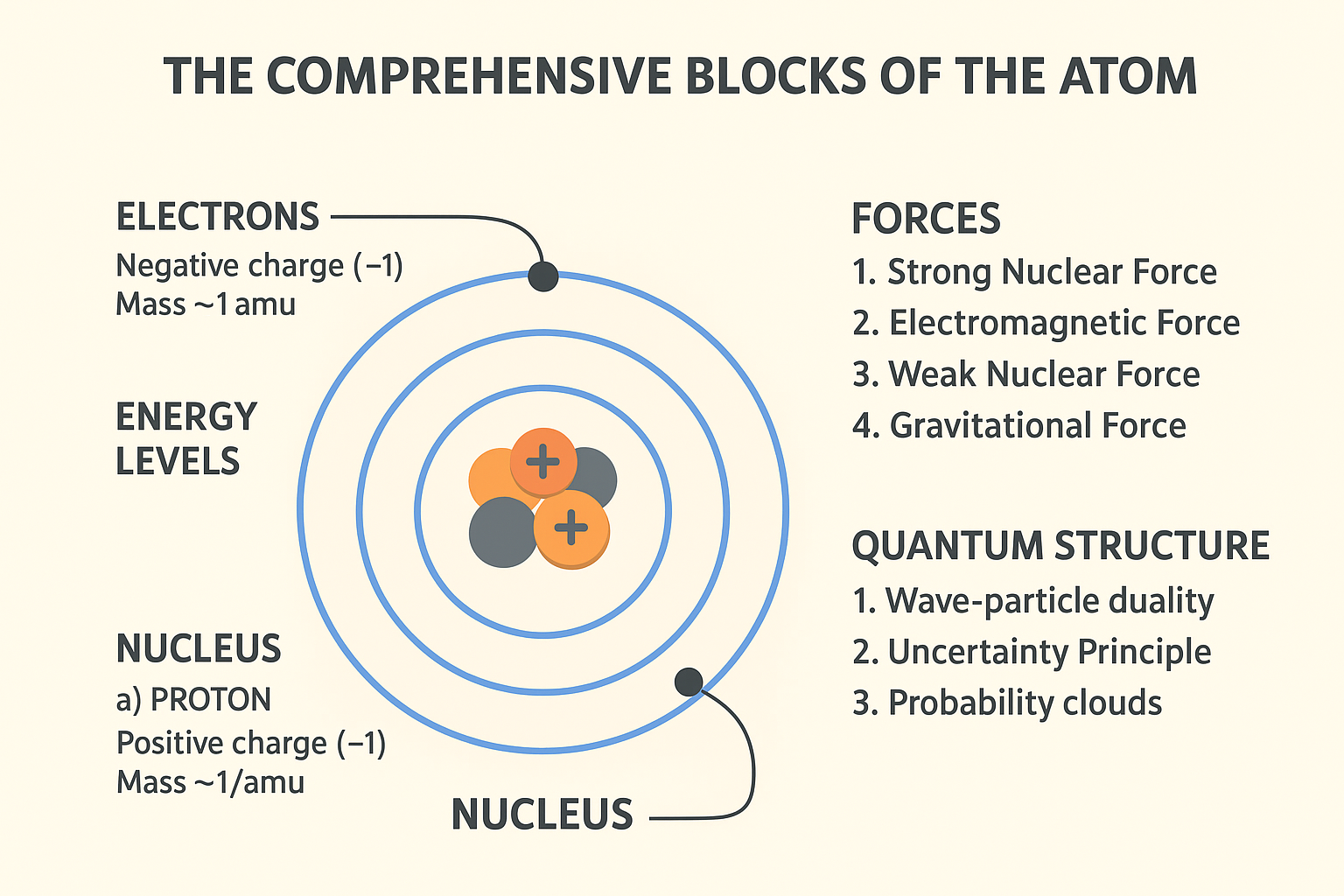

At the heart of every atom lies the nucleus, a dense, positively charged region that contains the vast majority of the atom’s mass. The nucleus is composed of two primary types of subatomic particles: protons and neutrons. These particles are collectively known as nucleons.

Protons

Protons are positively charged subatomic particles found within the atomic nucleus. Each proton carries a single unit of positive elementary charge (+1e). The number of protons in an atom’s nucleus, known as the atomic number (Z), defines the element. For instance, an atom with one proton is always hydrogen, an atom with six protons is always carbon, and an atom with eight protons is always oxygen. Protons have a mass of approximately 1 atomic mass unit (amu), which is roughly 1.672 × 10^-27 kilograms.

Neutrons

Neutrons are neutral (uncharged) subatomic particles also located within the atomic nucleus. While they do not contribute to the atom’s charge, they play a crucial role in stabilizing the nucleus, especially in heavier elements, by counteracting the electrostatic repulsion between positively charged protons. Like protons, neutrons have a mass of approximately 1 amu (about 1.675 × 10^-27 kilograms), making them slightly heavier than protons. The sum of protons and neutrons in an atom’s nucleus gives its mass number (A). Atoms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons, leading to isotopes.

The Strong Nuclear Force

The protons within the nucleus, being positively charged, naturally repel each other due to electromagnetic forces. However, the nucleus remains stable due to a much stronger attractive force known as the strong nuclear force (or strong interaction). This fundamental force acts over very short distances, binding protons and neutrons together with immense strength, overcoming the electrostatic repulsion between protons. Without the strong nuclear force, atomic nuclei would disintegrate.

Electrons and Electron Shells

Surrounding the atomic nucleus is a cloud of negatively charged particles called electrons. Unlike protons and neutrons, which reside in the dense nucleus, electrons occupy specific energy levels or ‘shells’ around the nucleus. These shells are often visualized as orbits, though the actual behavior of electrons is more complex and described by quantum mechanics.

Electrons

Electrons are fundamental particles, meaning they are not composed of smaller particles. Each electron carries a single unit of negative elementary charge (-1e), balancing the positive charge of the protons in a neutral atom. Electrons are significantly lighter than protons and neutrons, with a mass of approximately 9.109 × 10^-31 kilograms, which is about 1/1836th the mass of a proton. Their small mass and high speed allow them to occupy a relatively large volume around the nucleus.

Electron Shells and Energy Levels

Electrons are arranged in distinct energy levels or electron shells, often labeled K, L, M, N, and so on, or by principal quantum numbers (n=1, 2, 3, 4…). Each shell can hold a specific maximum number of electrons. The innermost shell (K or n=1) can hold up to 2 electrons, the second shell (L or n=2) up to 8 electrons, and the third shell (M or n=3) up to 18 electrons. The electrons in the outermost shell, known as valence electrons, are particularly important as they determine an atom’s chemical properties and its ability to form bonds with other atoms.

Electron Configuration

The arrangement of electrons in these shells and subshells is called the electron configuration. Atoms tend to achieve a stable electron configuration, often by having a full outermost shell. This drive for stability is what governs chemical reactions and the formation of molecules. Electrons can move between energy levels by absorbing or emitting energy in the form of photons.

Subatomic Particles Beyond Protons, Neutrons, and Electrons

While protons, neutrons, and electrons are the most commonly discussed subatomic particles when describing atomic structure, the field of particle physics reveals a much richer and more complex world of fundamental constituents. Protons and neutrons themselves are not fundamental particles; they are composite particles made up of even smaller entities called quarks.

Quarks

Quarks are fundamental particles that combine to form hadrons, which include baryons (like protons and neutrons) and mesons. There are six types, or ‘flavors,’ of quarks: up, down, charm, strange, top, and bottom. Each quark also has an associated ‘color’ charge (red, green, or blue), a property related to the strong nuclear force. Protons are composed of two up quarks and one down quark (uud), while neutrons are composed of one up quark and two down quarks (udd).

Leptons

Electrons belong to a class of fundamental particles called leptons. Besides the electron, there are two other charged leptons: the muon and the tau, each progressively heavier than the electron. Each charged lepton also has an associated neutral particle called a neutrino (electron neutrino, muon neutrino, and tau neutrino). Neutrinos are extremely light and interact very weakly with other matter.

Bosons

Bosons are fundamental particles that mediate forces. The four fundamental forces of nature are mediated by different bosons:

•Photons: Mediate the electromagnetic force, responsible for light and all electromagnetic phenomena.

•Gluons: Mediate the strong nuclear force, binding quarks together to form protons and neutrons, and holding the nucleus together.

•W and Z Bosons: Mediate the weak nuclear force, responsible for radioactive decay.

•Higgs Boson: Associated with the Higgs field, which gives other fundamental particles their mass.

Antimatter

For every particle, there exists an antiparticle with the same mass but opposite charge and other quantum numbers. For example, the antiparticle of an electron is a positron (a positively charged electron). When a particle and its antiparticle meet, they annihilate each other, converting their mass into energy.

Properties of Subatomic Particles

Each subatomic particle possesses distinct properties that define its role and behavior within the atom and in the broader universe. The most significant of these properties include charge, mass, and spin.

Charge

Electric charge is a fundamental property of matter that determines how particles interact with electromagnetic fields. Protons carry a positive charge (+1e), electrons carry a negative charge (-1e), and neutrons are electrically neutral (0 charge). The balance between protons and electrons dictates an atom’s overall charge. A neutral atom has an equal number of protons and electrons. Ions are formed when an atom gains or loses electrons, resulting in a net positive or negative charge.

Mass

Mass is a measure of an object’s resistance to acceleration. At the atomic level, mass is often expressed in atomic mass units (amu). Protons and neutrons have masses very close to 1 amu, with neutrons being slightly heavier. Electrons, in contrast, are significantly lighter, with a mass approximately 1/1836th that of a proton. The vast majority of an atom’s mass is concentrated in its nucleus due to the combined mass of protons and neutrons.

Spin

Spin is an intrinsic form of angular momentum carried by elementary particles, and it is a purely quantum mechanical phenomenon with no direct classical analogue. It can be thought of as an internal rotation, though this analogy is imperfect. Subatomic particles have a characteristic spin value, which is quantized. For example, electrons, protons, and neutrons all have a spin of 1/2. Particles with half-integer spins (like electrons, protons, and neutrons) are called fermions, and they obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which states that no two identical fermions can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. Particles with integer spins (like photons and gluons) are called bosons, and they do not obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle.

Conclusion

Atoms, the minuscule yet mighty constituents of all matter, are far from simple. Their intricate structure, governed by the interplay of protons, neutrons, and electrons, dictates the chemical properties of every element. Beyond these familiar particles lies a fascinating realm of quarks, leptons, and bosons, each playing a crucial role in the fundamental forces that shape our universe. Understanding these comprehensive blocks of atoms is not only essential for comprehending chemistry and physics but also for unlocking the mysteries of the cosmos itself. From the stability of stars to the complexity of life, the atom remains a testament to the profound elegance of nature’s design.

Be First to Comment