Introduction

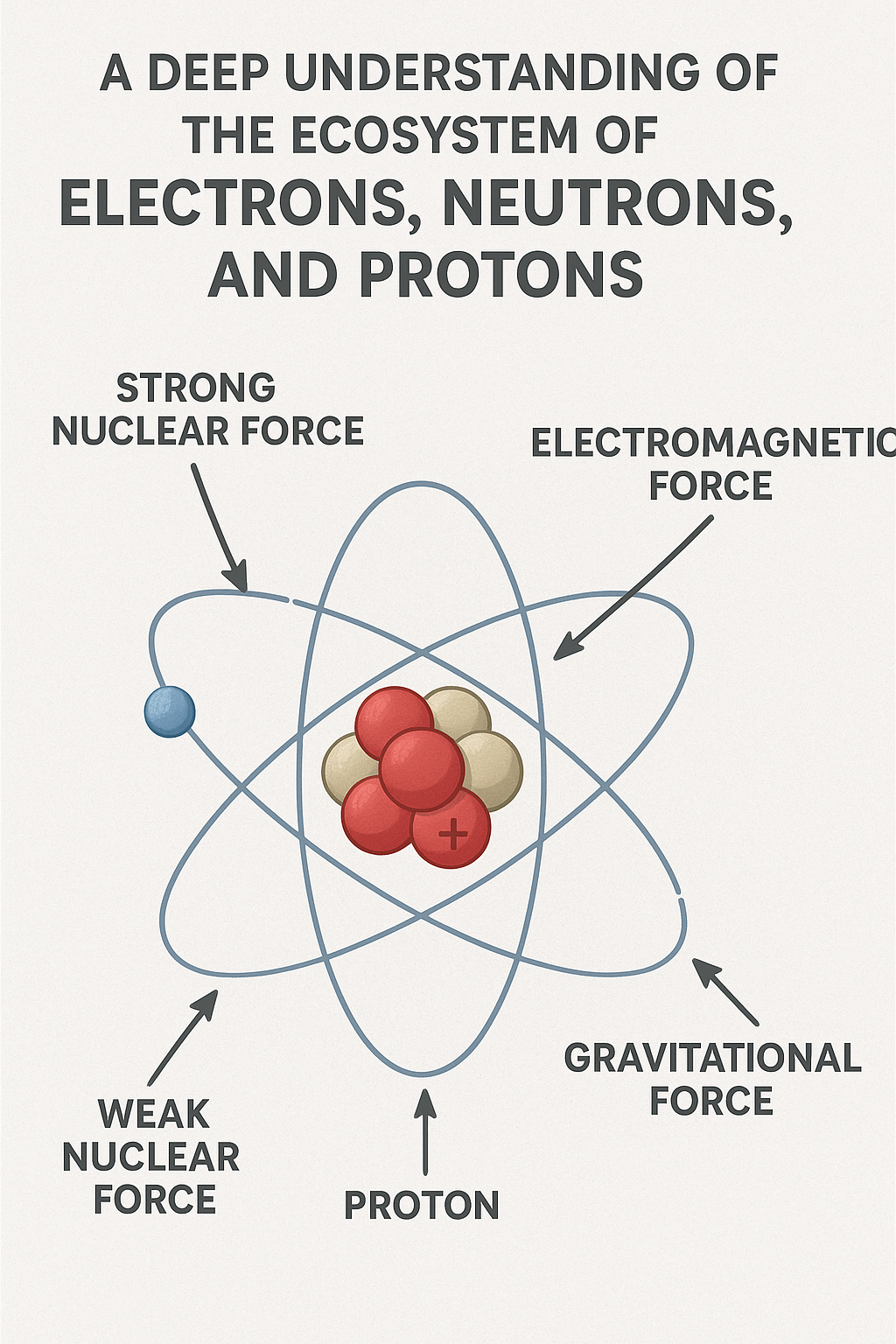

The universe, in all its magnificent complexity, is built upon a remarkably elegant foundation. At the heart of every atom—from the hydrogen in distant stars to the carbon in our bodies—lies an intricate ecosystem of three fundamental particles: electrons, neutrons, and protons. These subatomic constituents don’t merely coexist; they engage in a sophisticated dance governed by the fundamental forces of nature, creating the matter we observe and interact with daily.

Understanding this subatomic ecosystem requires us to journey into a realm where classical intuition fails, where particles behave as waves, where empty space teems with energy, and where the very act of observation influences reality. This is the quantum world, and it is here that we find the true nature of matter.

The Fundamental Players

Protons: The Positive Anchors

The proton stands as one of nature’s most stable particles. With a positive electric charge of +1 elementary charge and a mass of approximately 1.673 × 10⁻²⁷ kilograms, the proton defines the very identity of an atom. The number of protons in an atom’s nucleus determines which element it is—one proton makes hydrogen, six make carbon, 79 make gold. This number, called the atomic number, is the atomic identity card that cannot be changed without transmutation.

But protons are not elementary particles in the truest sense. They are composite particles, each consisting of three quarks bound together by the strong nuclear force. Specifically, a proton contains two “up” quarks (each with a charge of +2/3) and one “down” quark (with a charge of -1/3), giving the proton its net positive charge. These quarks are held together by particles called gluons, which mediate the strong force, creating one of the most powerful bonds in nature.

The proton’s internal structure is far from static. The quarks constantly exchange gluons, creating a roiling sea of quantum activity. Virtual quark-antiquark pairs pop in and out of existence within the proton’s confines, and the gluons themselves can briefly split into more gluons. This dynamic interior means that the proton’s mass doesn’t simply come from the sum of its constituent quarks—in fact, the quarks themselves account for only about 1% of the proton’s mass. The remainder comes from the binding energy of the strong force, a beautiful manifestation of Einstein’s E=mc².

Neutrons: The Neutral Stabilizers

The neutron, discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, is the proton’s slightly heavier cousin. With no electric charge and a mass of 1.675 × 10⁻²⁷ kilograms (about 0.1% heavier than a proton), neutrons play a crucial stabilizing role in atomic nuclei.

Like protons, neutrons are composite particles made of quarks—one up quark and two down quarks, which gives them their neutral charge. This small difference in quark composition leads to profound differences in behavior. While protons are remarkably stable (with a half-life exceeding 10³⁴ years, and possibly infinite), free neutrons are unstable, decaying with a half-life of about 15 minutes through a process called beta decay. A neutron transforms into a proton, emitting an electron and an antineutrino in the process.

However, when neutrons are bound within atomic nuclei, they can be stable, sometimes for billions of years. This stability is context-dependent, determined by the delicate balance of forces within the nucleus. Neutrons act as nuclear “glue,” providing additional strong force attraction without adding repulsive electromagnetic force, allowing heavier elements to exist despite the electromagnetic repulsion between their many protons.

Electrons: The Quantum Clouds

Electrons are fundamentally different from protons and neutrons. They are true elementary particles—leptons—with no internal structure as far as we can tell. An electron carries a negative charge of -1 elementary charge (exactly opposite to the proton’s charge) and has a minuscule mass of 9.109 × 10⁻³¹ kilograms, roughly 1/1836th the mass of a proton.

Electrons inhabit a quantum realm around the nucleus that defies classical description. They don’t orbit the nucleus like planets around a sun; instead, they exist in probabilistic clouds called orbitals. The famous Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle tells us we cannot simultaneously know an electron’s exact position and momentum—the very act of measuring one disturbs the other.

These orbitals are solutions to the Schrödinger equation, mathematical descriptions of the quantum states available to electrons. Each orbital has a specific energy level and a characteristic shape—some spherical (s orbitals), some dumbbell-shaped (p orbitals), and others more complex (d and f orbitals). Electrons fill these orbitals according to the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which states that no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously.

The Nuclear Ecosystem

The Strong Force: Nuclear Glue

At the center of every atom (except hydrogen-1) lies a nucleus containing multiple protons and neutrons bound together in an incredibly small space—about 10⁻¹⁵ meters in radius, roughly 100,000 times smaller than the atom itself. This tight packing creates a paradox: protons, all carrying positive charges, should violently repel each other according to electromagnetic force. Yet nuclei hold together, many remaining stable for billions of years.

The answer lies in the strong nuclear force, one of the four fundamental forces of nature and the most powerful force we know. Operating at distances less than about 3 femtometers (3 × 10⁻¹⁵ meters), the strong force between nucleons (protons and neutrons) overcomes electromagnetic repulsion. This force is effectively mediated by the exchange of pions between nucleons, though at a deeper level, it arises from the color force between quarks mediated by gluons.

The strong force has peculiar properties. Unlike gravity or electromagnetism, which weaken with distance, the strong force between quarks actually increases with distance, a property called confinement. This is why we never observe free quarks in nature—pulling quarks apart requires so much energy that new quark-antiquark pairs are created before the original quarks can be separated.

Nuclear Stability and the Valley of Beta Stability

Not all combinations of protons and neutrons form stable nuclei. The relationship between neutron number and proton number determines nuclear stability, creating what physicists call the “valley of beta stability” when plotted on a chart of nuclides.

For light elements, stable nuclei generally have roughly equal numbers of protons and neutrons. Carbon-12, for instance, has six protons and six neutrons. However, as atoms get heavier, stable nuclei require increasingly more neutrons than protons. Lead-208, a stable isotope, has 82 protons but 126 neutrons. This is because the electromagnetic repulsion between protons grows with the number of protons, while the strong force is short-range and doesn’t affect all protons equally. Extra neutrons provide additional attractive strong force without adding electromagnetic repulsion.

Nuclei that deviate from this valley are unstable and undergo radioactive decay to move toward stability. Those with too many neutrons undergo beta-minus decay (neutron → proton + electron + antineutrino), while those with too few neutrons undergo beta-plus decay or electron capture (proton → neutron + positron + neutrino).

Magic Numbers and Nuclear Shell Structure

Just as electrons occupy shells around the nucleus, nucleons within the nucleus occupy quantum shells. Certain numbers of protons or neutrons—2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, and 126—correspond to filled nuclear shells, creating unusually stable configurations called “magic numbers.”

Nuclei with magic numbers of protons or neutrons are more stable and abundant in nature. Lead-208, with both 82 protons (magic) and 126 neutrons (magic), is doubly magic and exceptionally stable. Helium-4, with two protons and two neutrons (both magic numbers for its size), is so stable that it’s produced as the alpha particle in many radioactive decays.

This shell structure arises from the quantum mechanical properties of nucleons in the nuclear potential well, similar to how electron shells arise from the electromagnetic potential of the nucleus. The nuclear shell model, developed by Maria Goeppert Mayer and J. Hans D. Jensen (who shared the 1963 Nobel Prize for this work), explains many properties of nuclei including their stability, spin, and magnetic moments.

The Electron Cloud: Chemistry’s Foundation

Quantum Numbers and Orbital Architecture

Each electron in an atom is described by four quantum numbers that completely specify its quantum state:

- Principal quantum number (n): Determines the electron’s energy level and average distance from the nucleus. Values are positive integers (1, 2, 3…), with higher numbers indicating higher energy and greater distance.

- Angular momentum quantum number (l): Determines the orbital’s shape. Values range from 0 to n-1. l=0 corresponds to s orbitals (spherical), l=1 to p orbitals (dumbbell-shaped), l=2 to d orbitals, and l=3 to f orbitals (increasingly complex shapes).

- Magnetic quantum number (mₗ): Determines the orbital’s orientation in space. Values range from -l to +l, including zero. For example, when l=1 (p orbital), mₗ can be -1, 0, or +1, corresponding to the three p orbitals oriented along different axes.

- Spin quantum number (mₛ): Describes the electron’s intrinsic angular momentum or “spin.” Values are either +1/2 (“spin up”) or -1/2 (“spin down”). Despite the name, this isn’t literally the electron spinning; it’s an intrinsic quantum property.

The Pauli Exclusion Principle dictates that no two electrons in an atom can have identical sets of all four quantum numbers. This principle is responsible for the structure of the periodic table and the very existence of chemistry as we know it.

Electron Configuration and the Periodic Table

Electrons fill orbitals in a specific order, generally from lowest to highest energy: 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, 7p. This order, while it has some irregularities, is determined by the complex interplay between the nuclear attraction and electron-electron repulsion.

This filling pattern creates the periodic table’s structure. Elements in the same column (group) have similar outer electron configurations, leading to similar chemical properties. The noble gases (helium, neon, argon, etc.) have filled outer shells, making them chemically inert. The alkali metals (lithium, sodium, potassium, etc.) have one electron beyond a noble gas configuration, making them highly reactive.

Bonding: Where Electrons Bridge Atoms

Chemical bonds—the forces that hold molecules together—arise entirely from electromagnetic interactions between electrons and nuclei. The three primary types of bonds all involve electron behavior:

Ionic bonds form when one atom transfers electrons to another, creating oppositely charged ions that attract each other. Sodium (with one easily removed outer electron) and chlorine (needing one electron to complete its outer shell) form sodium chloride through this mechanism.

Covalent bonds form when atoms share electrons, with the shared electrons spending time near both nuclei. The bond is quantum mechanical in nature—the shared electrons occupy molecular orbitals that encompass both atoms, and the system’s total energy is lower than that of separated atoms.

Metallic bonds occur in metals, where outer electrons become delocalized, forming a “sea” of electrons that moves freely between positive ion cores. This electron mobility explains metals’ electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, malleability, and luster.

The Intricate Balance: How the Ecosystem Functions

Electromagnetic Force: The Organizational Principle

While the strong force binds the nucleus, electromagnetic force organizes the atom as a whole. The positively charged nucleus attracts negatively charged electrons, keeping them bound to the atom. The strength of this attraction determines atomic size—elements with more protons pull electrons more tightly, making atoms smaller going left to right across the periodic table (even though they’re adding electrons).

The electromagnetic force operates on a vastly different scale than the strong force. While the strong force operates at femtometer distances, electromagnetic effects extend to atomic scales (picometers) and beyond. The electromagnetic force also follows an inverse-square law, meaning it weakens with the square of distance but never completely vanishes.

Energy Levels and Photon Interactions

Electrons can only exist in specific energy levels within an atom, creating a quantum ladder of allowed states. When an electron absorbs a photon with exactly the right energy, it jumps to a higher level. When it falls back down, it emits a photon carrying away the energy difference.

This quantization of energy levels gives each element a unique spectral fingerprint—specific wavelengths of light it can absorb or emit. Hydrogen’s Balmer series, for instance, produces visible light at wavelengths of 656 nm (red), 486 nm (cyan), 434 nm (blue), and 410 nm (violet) when electrons fall from higher levels to the n=2 level.

Spectroscopy, the study of these spectral lines, allows us to determine the composition of distant stars, analyze chemical samples, and even detect exoplanets. It’s one of chemistry’s and astronomy’s most powerful tools, all based on the quantized nature of electron energy levels.

Wave-Particle Duality: The Quantum Truth

Perhaps the most profound aspect of the subatomic ecosystem is wave-particle duality. Electrons, protons, and neutrons all exhibit both particle and wave properties, depending on how they’re observed.

An electron can be diffracted like a wave, creating interference patterns when passed through double slits. Yet when detected, it always arrives at a specific point, like a particle. This duality isn’t a defect in our understanding—it’s a fundamental feature of quantum reality. These particles are neither waves nor particles in the classical sense; they’re quantum entities that exhibit properties of both, depending on the measurement context.

The de Broglie wavelength, λ = h/p (where h is Planck’s constant and p is momentum), describes the wave nature of particles. For protons and neutrons in the nucleus, with high momenta confined in tiny spaces, wavelengths are extremely short. For electrons in atoms, wavelengths are comparable to atomic dimensions, making their wave nature crucial to understanding atomic structure.

Exotic Phenomena and Edge Cases

Isotopes: Nuclear Variations

While the number of protons defines an element, the number of neutrons can vary, creating isotopes. Carbon always has six protons, but carbon-12 (six neutrons), carbon-13 (seven neutrons), and carbon-14 (eight neutrons) are all isotopes of carbon.

Most elements have multiple stable isotopes. Tin holds the record with ten stable isotopes. Some isotopes are unstable (radioactive), like carbon-14, which decays with a half-life of 5,730 years—the basis for radiocarbon dating. The existence of isotopes demonstrates that nuclear structure is more nuanced than simple proton counting.

Ionization: Disturbing the Electron Balance

Atoms normally have equal numbers of protons and electrons, making them electrically neutral. However, atoms can gain or lose electrons, becoming ions. Positive ions (cations) have fewer electrons than protons; negative ions (anions) have more electrons than protons.

Ionization energy—the energy required to remove an electron—varies systematically across the periodic table. Noble gases have high ionization energies (their electron configurations are stable), while alkali metals have low ionization energies (they “want” to lose their single outer electron). This pattern drives much of chemistry’s reactivity trends.

Multiple ionization is also possible. Iron can lose two electrons to form Fe²⁺ or three to form Fe³⁺. Each successive ionization requires more energy, as removing electrons from an increasingly positive ion becomes harder.

Nuclear Fission and Fusion: Extreme Nuclear Reorganization

The nuclear ecosystem can be dramatically rearranged under extreme conditions. Nuclear fission splits heavy nuclei into lighter ones, releasing energy because the products have higher binding energy per nucleon. Uranium-235, when struck by a neutron, can split into various combinations of lighter elements, releasing additional neutrons that can trigger a chain reaction.

Nuclear fusion combines light nuclei into heavier ones, also releasing energy for elements lighter than iron. The sun fuses hydrogen into helium through a multi-step process, releasing the energy that makes life on Earth possible. Fusion requires extreme temperatures and pressures to overcome electromagnetic repulsion between positively charged nuclei.

The relationship between nuclear mass and binding energy creates a curve with a peak near iron-56. Nuclei lighter than iron release energy through fusion; nuclei heavier than iron release energy through fission. This is why iron is the endpoint of stellar nucleosynthesis in normal stars—fusing elements heavier than iron requires energy input rather than releasing it.

Antimatter: The Mirror Ecosystem

For every particle, there exists an antiparticle with the same mass but opposite charge and other quantum numbers. The antiproton is negatively charged, the positron (antielectron) is positively charged, and the antineutron, while electrically neutral, has opposite quantum numbers from the neutron.

When matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate, converting their mass entirely into energy according to E=mc². A proton-antiproton collision produces photons and other particles, releasing tremendous energy. Despite this symmetry, our universe is overwhelmingly composed of matter rather than antimatter—one of physics’ great unsolved mysteries.

Scientists have created antihydrogen atoms (an antiproton orbited by a positron) and briefly trapped them for study. These antimatter atoms should behave identically to regular hydrogen if the fundamental symmetries of physics hold, and so far, experimental evidence supports this.

Practical Applications: The Ecosystem at Work

Medical Imaging and Treatment

Understanding the subatomic ecosystem enables powerful medical technologies. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans utilize antimatter—radioactive isotopes that emit positrons, which annihilate with electrons, producing gamma rays that reveal metabolic activity. MRI machines exploit the magnetic properties of protons in hydrogen atoms, manipulating their nuclear spins to create detailed images of soft tissue.

Radiation therapy for cancer uses our understanding of how high-energy particles and photons interact with matter. Proton therapy delivers protons that deposit most of their energy at a specific depth (the Bragg peak), sparing surrounding tissue better than conventional radiation.

Nuclear Energy

Nuclear power plants exploit the energy released from uranium fission, converting nuclear binding energy into heat, then electricity. The controlled chain reaction in a reactor core carefully balances neutron production and absorption. Modern reactor designs use the intrinsic properties of materials—like how water moderates (slows) neutrons to optimal speeds for fission but expands and becomes less effective if temperature rises—to create passive safety features.

Future fusion reactors aim to harness the same process that powers stars. Projects like ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) are attempting to confine hydrogen plasmas at temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius, where fusion can occur at useful rates.

Semiconductors and Electronics

Modern electronics depend on precisely controlling electron behavior in materials. Semiconductors like silicon have electron band structures that allow their electrical properties to be manipulated by adding tiny amounts of other elements (doping). N-type doping adds atoms with extra electrons; p-type doping adds atoms with electron “holes.” Combining these creates transistors, the fundamental building blocks of all modern electronics.

Quantum dots are nanoscale semiconductor crystals where electrons are confined to such small spaces that quantum effects dominate, allowing precise control over their optical and electronic properties. They’re used in displays, solar cells, and biomedical imaging.

Dating Techniques

Radioactive decay of unstable isotopes provides natural clocks for determining ages. Carbon-14 dating uses the decay of carbon-14 (absorbed by living organisms) to date organic materials up to about 50,000 years old. Uranium-lead dating uses the decay of uranium-238 to lead-206 (with a half-life of 4.5 billion years) to date rocks and determine Earth’s age.

These techniques rest entirely on understanding how neutron-proton ratios affect nuclear stability and how unstable nuclei transform through radioactive decay.

Unresolved Mysteries and Frontiers

The Strong CP Problem

The strong force, as described by quantum chromodynamics (QCD), could theoretically violate the combined symmetry of charge conjugation and parity (CP symmetry). However, experiments show that the strong interaction conserves CP symmetry to an extraordinary degree. Why this is the case remains mysterious and is known as the strong CP problem. The hypothetical axion particle has been proposed to solve this problem, and searches for axions continue.

Proton Decay

Grand Unified Theories suggest that protons might be unstable over extremely long timescales, eventually decaying into lighter particles. Experiments have searched for proton decay for decades, monitoring vast tanks of ultra-pure water for the telltale signature of a proton’s demise. So far, no convincing evidence has been found, setting the proton’s half-life at greater than 10³⁴ years—far longer than the age of the universe. Whether protons are truly stable or just extremely long-lived remains an open question.

Neutron Lifetime Puzzle

Precise measurements of the neutron’s lifetime (how long a free neutron survives before beta decay) depend on the measurement method. “Bottle” experiments that trap neutrons and count how many remain give a lifetime of about 879 seconds. “Beam” experiments that measure the products of neutron decay give about 888 seconds. This nine-second discrepancy, though small, is statistically significant and remains unexplained. It could indicate unknown physics or subtle experimental issues.

Quark-Gluon Plasma

At extreme temperatures and densities, neutrons and protons dissolve into their constituent quarks and gluons, forming a quark-gluon plasma—a state of matter that existed microseconds after the Big Bang. Particle colliders like the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) create these conditions briefly by colliding heavy nuclei at near-light speed. Understanding this state provides insights into the early universe and the nature of the strong force.

Conclusion

The ecosystem of electrons, neutrons, and protons is a testament to nature’s elegant complexity. These three particle types, following quantum mechanical laws and governed by fundamental forces, create the entire material world. From the nuclear furnaces of stars to the biochemistry of life, from the circuits in our computers to the rocks beneath our feet, everything emerges from the interplay of these subatomic constituents.

The proton provides identity and positive charge, defining elements and anchoring the atom. The neutron provides stability, allowing heavy elements to exist and offering a buffer against electromagnetic repulsion. The electron provides versatility, creating chemistry through its quantum behavior and forming the bonds between atoms that make molecules, materials, and life possible.

Yet for all we’ve learned—and our understanding is profound—mysteries remain. The precise nature of quark confinement, the origin of matter-antimatter asymmetry, the exact value of the neutron lifetime, and the possibility of proton decay all represent frontiers where our understanding remains incomplete.

What’s remarkable is that three types of particles, following rules we can write in equations, create such astonishing diversity. Every color you’ve seen, every flavor you’ve tasted, every material you’ve touched emerges from different arrangements and interactions of electrons, neutrons, and protons. This subatomic ecosystem, invisible to our senses yet fundamental to our existence, remains one of science’s most profound and beautiful discoveries.

Be First to Comment