Introduction

Often referred to as the “powerhouses of the cell,” mitochondria are remarkable organelles that serve as the energy-producing factories within nearly every cell in the human body. These double-membraned structures are far more than simple energy generators; they are sophisticated biological machines that orchestrate numerous critical cellular processes essential for life itself. From powering our thoughts to enabling our muscles to contract, mitochondria are the unsung heroes working tirelessly behind the scenes to sustain human existence.

The discovery of mitochondria dates back to the 1850s when German pathologist Rudolf Virchow first observed them under a microscope. However, it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that scientists began to fully appreciate their crucial role in cellular metabolism and energy production. Today, we understand that mitochondrial dysfunction underlies numerous diseases and plays a significant role in aging, making these organelles a focal point of modern medical research.

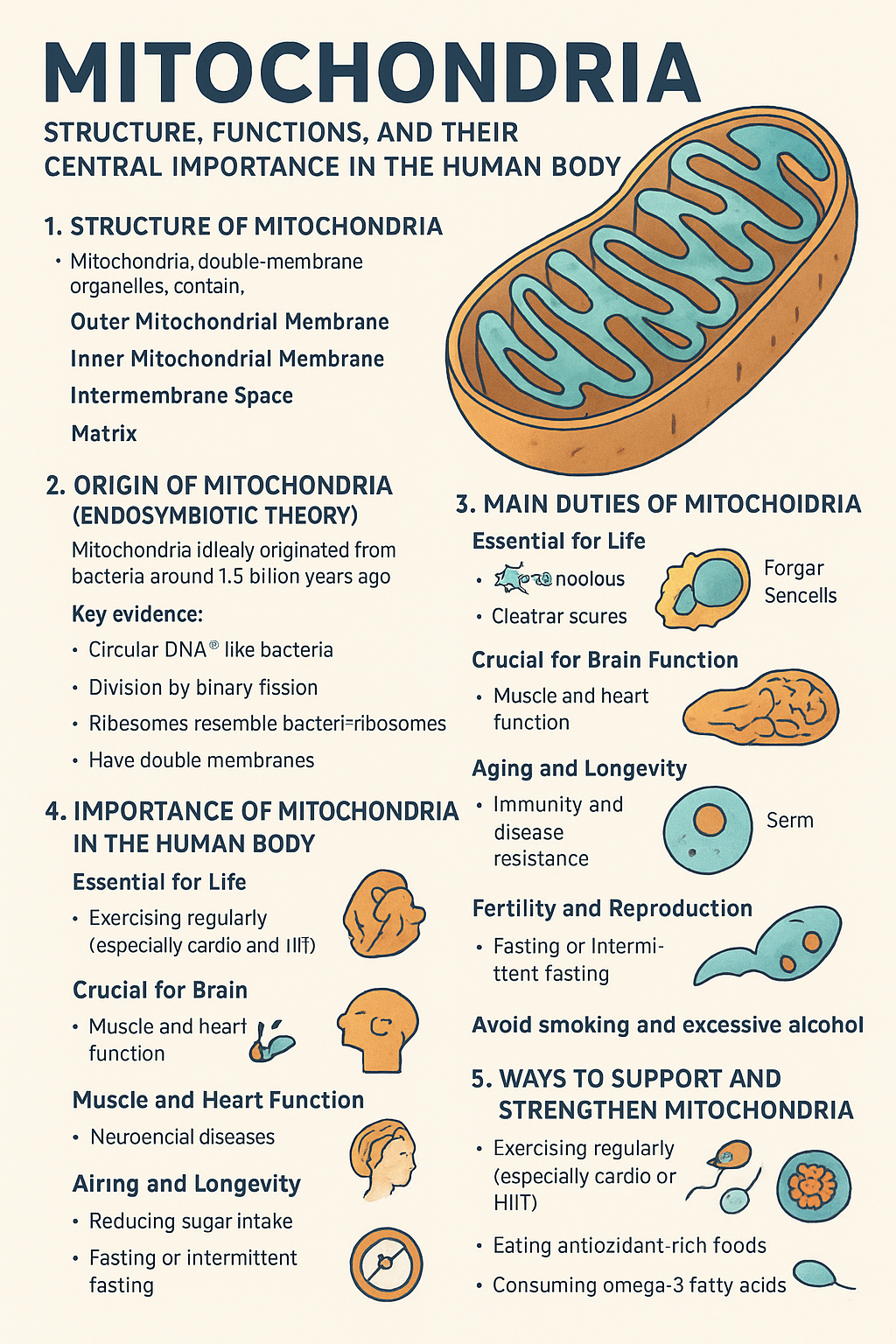

Structure and Organization of Mitochondria

Basic Architecture

Mitochondria possess a unique double-membrane structure that is fundamental to their function. The outer mitochondrial membrane serves as the organelle’s boundary, separating it from the cell’s cytoplasm while allowing certain molecules to pass through specialized protein channels. This membrane contains porins, large protein complexes that create pores allowing molecules smaller than 5,000 daltons to freely diffuse.

The inner mitochondrial membrane is where the magic of energy production truly occurs. This membrane is extensively folded into structures called cristae, which dramatically increase the surface area available for energy-producing reactions. The cristae house the electron transport chain complexes and ATP synthase, the molecular machinery responsible for generating the cell’s primary energy currency.

Between these two membranes lies the intermembrane space, a narrow compartment that plays a crucial role in the proton gradient essential for ATP production. The innermost compartment, known as the mitochondrial matrix, contains the enzymes necessary for the citric acid cycle, mitochondrial DNA, ribosomes, and various cofactors required for cellular respiration.

Mitochondrial DNA and Inheritance

One of the most fascinating aspects of mitochondria is their possession of their own genetic material. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a circular, double-stranded molecule that contains 37 genes encoding 13 proteins, 22 transfer RNAs, and 2 ribosomal RNAs. This genetic autonomy is evidence supporting the endosymbiotic theory, which suggests that mitochondria were once free-living bacteria that formed a symbiotic relationship with early eukaryotic cells.

Unlike nuclear DNA, which is inherited from both parents, mitochondrial DNA is maternally inherited. This unique inheritance pattern has profound implications for genetic diseases and has made mtDNA a valuable tool for evolutionary studies and forensic investigations.

Primary Functions of Mitochondria

1. Cellular Respiration and ATP Production

The primary and most well-known function of mitochondria is cellular respiration – the process by which cells break down glucose and other organic molecules to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the universal energy currency of cells. This complex process occurs in several stages:

Glycolysis: While this initial step occurs in the cytoplasm, its products (pyruvate) enter the mitochondria to continue the energy extraction process.

Pyruvate Oxidation: In the mitochondrial matrix, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA, releasing carbon dioxide and generating NADH, an important electron carrier.

Citric Acid Cycle (Krebs Cycle): Also occurring in the matrix, this cycle systematically breaks down acetyl-CoA, producing additional NADH, FADH2, and GTP while releasing more carbon dioxide.

Electron Transport Chain and Oxidative Phosphorylation: This final stage occurs along the inner mitochondrial membrane. Electrons from NADH and FADH2 are passed through a series of protein complexes, releasing energy that is used to pump protons across the membrane, creating an electrochemical gradient. This gradient drives ATP synthase, which produces the majority of cellular ATP.

A single glucose molecule can yield up to 38 ATP molecules through this process, demonstrating the remarkable efficiency of mitochondrial energy production.

2. Fatty Acid Oxidation

Mitochondria are the exclusive site of fatty acid beta-oxidation in most cells. This process breaks down fatty acids to produce acetyl-CoA, which can then enter the citric acid cycle. Fatty acid oxidation is particularly important during periods of fasting or prolonged exercise when glucose stores become depleted. The liver and muscle tissues heavily rely on this process, and mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to serious metabolic disorders affecting fat metabolism.

3. Calcium Homeostasis

Mitochondria serve as important calcium storage and buffering systems within cells. They can rapidly uptake calcium ions from the cytoplasm through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter and release it through sodium-calcium exchangers. This function is crucial for:

- Regulating cytoplasmic calcium levels

- Modulating cellular signaling pathways

- Controlling muscle contraction

- Influencing neurotransmitter release

- Regulating enzyme activities

Calcium also plays a regulatory role within mitochondria themselves, affecting the activity of several enzymes involved in energy metabolism.

4. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production and Management

While often viewed negatively, mitochondria are the primary source of reactive oxygen species in most cells. These molecules, including superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, are natural byproducts of electron transport chain activity. While excessive ROS can cause cellular damage, they also serve important signaling functions and help regulate various cellular processes.

Mitochondria contain sophisticated antioxidant systems, including:

- Superoxide dismutase (SOD2)

- Catalase

- Glutathione peroxidase

- Various antioxidant molecules like coenzyme Q10

The balance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses is crucial for cellular health and plays a significant role in aging and disease processes.

5. Apoptosis Regulation

Mitochondria are central players in programmed cell death or apoptosis. They contain pro-apoptotic proteins such as cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) in their intermembrane space. When cells receive death signals or sustain irreparable damage, mitochondrial membranes become permeabilized, releasing these proteins into the cytoplasm where they activate caspases and other death-promoting pathways.

This function is essential for:

- Removing damaged or unnecessary cells

- Tissue development and remodeling

- Immune system function

- Cancer prevention

Tissue-Specific Importance

Brain and Nervous System

The brain consumes approximately 20% of the body’s total energy despite representing only 2% of body weight. Neurons are entirely dependent on mitochondrial function for their high energy demands. Mitochondria in neurons must:

- Support synaptic transmission

- Maintain membrane potentials

- Power axonal transport

- Support neurotransmitter synthesis

Mitochondrial dysfunction in the brain is associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases.

Heart and Cardiac Muscle

Cardiac muscle cells contain an exceptionally high density of mitochondria, comprising up to 40% of cell volume. The heart beats continuously throughout life, requiring a constant supply of ATP. Cardiac mitochondria must adapt to varying energy demands and efficiently utilize multiple fuel sources including fatty acids, glucose, and ketones.

Skeletal Muscle

Mitochondrial content and function in skeletal muscle vary dramatically based on fiber type and training status. Endurance exercise increases mitochondrial biogenesis, improving the muscle’s capacity for aerobic energy production. This adaptation is fundamental to physical fitness and athletic performance.

Liver

Hepatic mitochondria are crucial for:

- Gluconeogenesis

- Fatty acid oxidation

- Bile acid synthesis

- Detoxification processes

- Protein synthesis

The liver’s metabolic flexibility depends heavily on mitochondrial function, and hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to fatty liver disease and metabolic disorders.

Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Dynamics

Biogenesis

Mitochondrial biogenesis is the process by which new mitochondria are formed. This process is regulated by several key factors:

PGC-1α (Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha): Often called the “master regulator” of mitochondrial biogenesis, PGC-1α coordinates the expression of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins.

Nuclear Respiratory Factors (NRF-1 and NRF-2): These transcription factors regulate the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial function and biogenesis.

Mitochondrial Transcription Factor A (TFAM): This protein regulates mitochondrial DNA transcription and replication.

Factors that stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis include:

- Exercise

- Cold exposure

- Caloric restriction

- Certain hormones (thyroid hormones, catecholamines)

- Metabolic stress

Mitochondrial Dynamics

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that constantly undergo fusion and fission processes. These dynamics are essential for:

Fusion: Mediated by proteins like MFN1, MFN2, and OPA1, fusion allows:

- Sharing of metabolic resources

- DNA repair through complementation

- Maintenance of healthy mitochondrial populations

Fission: Controlled by proteins including DRP1 and FIS1, fission enables:

- Mitochondrial distribution during cell division

- Removal of damaged mitochondrial segments

- Adaptation to local energy demands

Disruption of mitochondrial dynamics is implicated in various diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders and metabolic diseases.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Disease

Primary Mitochondrial Diseases

Primary mitochondrial diseases are caused by mutations in either mitochondrial or nuclear genes that affect mitochondrial function. These rare but serious conditions include:

MELAS (Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-like episodes): Caused by mtDNA mutations affecting tRNA genes.

MERRF (Myoclonic Epilepsy with Ragged Red Fibers): Results from mutations in mitochondrial tRNA genes.

Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON): Affects complex I of the electron transport chain, leading to vision loss.

Kearns-Sayre Syndrome: Involves large-scale mtDNA deletions and affects multiple organ systems.

Secondary Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Many common diseases involve secondary mitochondrial dysfunction:

Diabetes: Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in pancreatic beta cells and insulin-sensitive tissues.

Cardiovascular Disease: Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and hypertension.

Neurodegenerative Diseases: Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS all show evidence of mitochondrial involvement.

Cancer: Many cancers exhibit altered mitochondrial metabolism, including the Warburg effect.

Aging: Accumulation of mitochondrial damage is considered a key mechanism of aging.

Factors Affecting Mitochondrial Health

Lifestyle Factors

Exercise: Regular physical activity is one of the most powerful stimulators of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Both aerobic and resistance exercise can improve mitochondrial health.

Diet: Nutritional factors that support mitochondrial health include:

- Adequate protein intake for enzyme synthesis

- Omega-3 fatty acids for membrane health

- Antioxidants (vitamins C and E, polyphenols)

- B-vitamins as cofactors for metabolic enzymes

- Minerals like magnesium and iron

Sleep: Quality sleep is essential for mitochondrial maintenance and repair processes.

Stress Management: Chronic stress can impair mitochondrial function through elevated cortisol levels and increased oxidative stress.

Environmental Factors

Various environmental toxins can damage mitochondria:

- Heavy metals (lead, mercury, cadmium)

- Pesticides and herbicides

- Air pollution

- Certain pharmaceuticals

- Alcohol and tobacco

Age-Related Changes

Mitochondrial function generally declines with age due to:

- Accumulation of mtDNA mutations

- Decreased antioxidant defenses

- Reduced mitochondrial biogenesis

- Impaired quality control mechanisms

- Changes in mitochondrial dynamics

Therapeutic Approaches and Future Directions

Current Therapeutic Strategies

Nutritional Supplements:

- Coenzyme Q10: Supports electron transport chain function

- PQQ (Pyrroloquinoline quinone): May stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis

- NAD+ precursors: Support cellular energy metabolism

- Alpha-lipoic acid: Provides antioxidant protection

Pharmaceutical Interventions:

- Metformin: Improves mitochondrial function in diabetes

- Idebenone: Used in some mitochondrial diseases

- Various antioxidants and metabolic modulators

Gene Therapy: Emerging approaches include:

- Mitochondrial replacement therapy

- Gene editing techniques (CRISPR/Cas9)

- Allotopic expression of mitochondrial genes

Promising Research Areas

Mitochondrial Transplantation: Experimental procedures involving the transfer of healthy mitochondria into damaged cells.

Mitophagy Enhancement: Strategies to improve the removal of damaged mitochondria through autophagy.

Artificial Mitochondria: Development of synthetic organelles that could supplement or replace damaged mitochondria.

Personalized Medicine: Tailoring treatments based on individual mitochondrial genotypes and functional assessments.

Exercise and Mitochondrial Adaptation

Molecular Mechanisms

Exercise triggers a complex cascade of molecular events that enhance mitochondrial function:

Immediate Effects:

- Increased calcium signaling

- Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)

- Enhanced ROS production (acting as signaling molecules)

Long-term Adaptations:

- Increased PGC-1α expression

- Enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis

- Improved electron transport chain efficiency

- Better antioxidant defenses

Types of Exercise and Mitochondrial Benefits

Endurance Exercise: Particularly effective for:

- Increasing mitochondrial density

- Improving oxidative capacity

- Enhancing fat oxidation

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): Provides:

- Time-efficient mitochondrial adaptations

- Improved mitochondrial respiratory capacity

- Enhanced metabolic flexibility

Resistance Training: Contributes to:

- Maintained mitochondrial function with aging

- Improved muscle quality

- Enhanced metabolic health

Nutritional Support for Mitochondrial Health

Macronutrients

Carbohydrates: Provide glucose for immediate energy needs but should be balanced to avoid excessive insulin responses.

Fats: Essential for:

- Membrane structure

- Fat-soluble vitamin absorption

- Ketone production during fasting states

Proteins: Critical for:

- Enzyme synthesis

- Maintaining muscle mass

- Providing amino acids for gluconeogenesis

Micronutrients

B-Vitamins: Essential cofactors for energy metabolism:

- B1 (Thiamine): Pyruvate dehydrogenase function

- B2 (Riboflavin): Component of FAD

- B3 (Niacin): Component of NAD+

- B5 (Pantothenic acid): Coenzyme A synthesis

Minerals:

- Iron: Essential for electron transport complexes

- Magnesium: Cofactor for numerous enzymes

- Zinc: Antioxidant enzyme function

- Selenium: Glutathione peroxidase activity

Antioxidants:

- Vitamin C: Water-soluble antioxidant

- Vitamin E: Membrane-bound antioxidant

- Polyphenols: Plant compounds with antioxidant properties

Conclusion

Mitochondria represent far more than simple cellular powerhouses; they are sophisticated organelles that integrate metabolism, signaling, and cellular fate decisions. Their proper function is essential for virtually every aspect of human health, from basic cellular energy production to complex processes like immune function and neuronal activity.

Understanding mitochondrial biology has opened new avenues for treating diseases ranging from rare genetic disorders to common conditions like diabetes and heart disease. As we continue to unravel the complexities of mitochondrial function, we gain deeper insights into the fundamental processes that sustain life.

The future of mitochondrial medicine holds great promise, with emerging therapies targeting mitochondrial dysfunction and novel approaches to enhance mitochondrial health. From the development of mitochondrial-targeted drugs to the potential for mitochondrial replacement therapy, we are entering an exciting era where our growing understanding of these remarkable organelles may translate into revolutionary treatments for human disease.

Maintaining mitochondrial health through lifestyle interventions – particularly exercise, proper nutrition, and stress management – remains one of the most accessible and effective strategies for promoting overall health and longevity. As we age, the importance of supporting our cellular powerhouses becomes increasingly critical, making mitochondrial health a key focus for healthy aging and disease prevention.

The study of mitochondria continues to reveal new surprises and complexities, reminding us that these ancient endosymbionts remain central to understanding life itself. Their dual role as both essential life-sustaining organelles and potential mediators of cellular death underscores the delicate balance that defines healthy cellular function. As we move forward, the integration of mitochondrial biology into mainstream medicine promises to revolutionize our approach to treating disease and promoting human health.

Be First to Comment