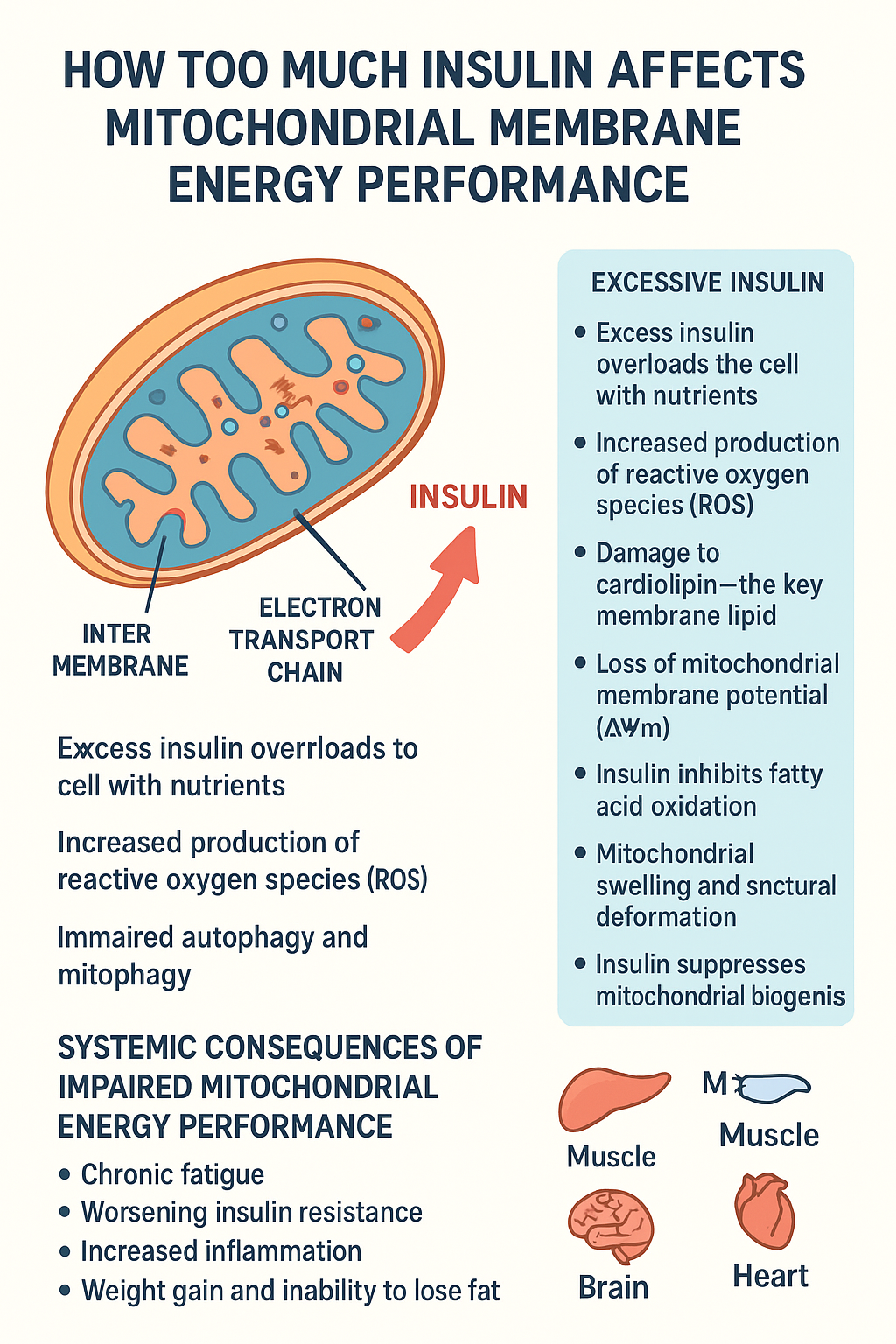

The Impact of Elevated Insulin on Mitochondrial Membrane Energy Performance: A Comprehensive Analysis

Introduction

The intricate relationship between insulin signaling and mitochondrial function represents one of the most critical intersections in cellular metabolism and human health. Mitochondria, often termed the “powerhouses of the cell,” are responsible for generating the vast majority of cellular energy through oxidative phosphorylation. The mitochondrial membrane, particularly the inner membrane, serves as the crucial site where this energy transformation occurs. When insulin levels become chronically elevated—a condition known as hyperinsulinemia—the delicate balance of mitochondrial membrane function can be profoundly disrupted, leading to cascading effects on cellular energy metabolism and overall physiological health.

This article explores the multifaceted ways in which high insulin levels affect mitochondrial membrane energy performance, examining the molecular mechanisms, physiological consequences, and broader implications for metabolic health and disease.

Understanding Mitochondrial Membrane Structure and Function

Before delving into insulin’s effects, it’s essential to understand the fundamental architecture and function of mitochondrial membranes. Mitochondria possess two distinct membranes: an outer membrane that is relatively permeable and an inner membrane that is highly selective and extensively folded into structures called cristae. These cristae dramatically increase the surface area available for energy production.

The inner mitochondrial membrane houses the electron transport chain, a series of protein complexes (Complexes I through IV) that create a proton gradient across the membrane. This gradient, representing stored potential energy, drives ATP synthase (Complex V) to produce adenosine triphosphate, the universal energy currency of cells. The efficiency of this process depends critically on the integrity and fluidity of the mitochondrial membrane, the proper organization of respiratory complexes, and the maintenance of appropriate electrochemical gradients.

The membrane’s lipid composition is particularly important, with cardiolipin—a unique phospholipid found almost exclusively in mitochondrial membranes—playing a crucial role in maintaining membrane structure and supporting the function of respiratory chain complexes. The membrane potential, typically around -180 millivolts, represents the driving force for ATP synthesis and must be carefully regulated to balance energy production with cellular needs.

Insulin Signaling and Mitochondrial Function: The Normal Relationship

Under physiological conditions, insulin plays important roles in regulating mitochondrial function and energy metabolism. When insulin binds to its receptor on the cell surface, it initiates a cascade of signaling events that influence mitochondrial biogenesis, substrate utilization, and oxidative capacity. Insulin normally promotes glucose uptake and directs nutrients toward either immediate energy production or storage, depending on cellular energy status.

In healthy metabolic states, insulin signaling enhances mitochondrial function by promoting the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of transcriptional coactivators like PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha). This supports the maintenance of a robust mitochondrial network capable of meeting cellular energy demands. Additionally, insulin influences the balance between glucose and fatty acid oxidation, helping cells adapt their fuel utilization to nutrient availability.

However, this beneficial relationship becomes disrupted when insulin levels remain chronically elevated, a situation increasingly common in modern metabolic disorders.

Hyperinsulinemia: The State of Chronically Elevated Insulin

Hyperinsulinemia typically develops in the context of insulin resistance, where cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals, prompting the pancreas to secrete ever-increasing amounts of insulin to maintain glucose homeostasis. This can occur in conditions such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and polycystic ovary syndrome. Importantly, hyperinsulinemia often precedes the development of overt diabetes and may represent an early driver of metabolic dysfunction rather than merely a compensatory response.

Chronic elevation of insulin creates a fundamentally different metabolic environment than the pulsatile insulin signaling seen in healthy individuals. Whereas insulin normally rises after meals and falls between them, allowing metabolic flexibility, hyperinsulinemia creates a state of constant insulin signaling that disrupts normal cellular responses and metabolic cycles.

Mechanisms of Insulin-Induced Mitochondrial Membrane Dysfunction

Disruption of Membrane Potential and Proton Gradient

One of the primary ways elevated insulin affects mitochondrial membrane energy performance is through alterations in membrane potential. Chronic hyperinsulinemia has been associated with hyperpolarization of the mitochondrial membrane in some contexts and depolarization in others, depending on the tissue and metabolic state. Both extremes are problematic for optimal energy production.

Hyperpolarization can lead to increased production of reactive oxygen species as electrons back up in the electron transport chain. The membrane becomes “too charged,” causing electrons to leak prematurely and react with oxygen to form superoxide and other reactive molecules. This oxidative stress damages membrane lipids, proteins, and even mitochondrial DNA, creating a vicious cycle of dysfunction.

Conversely, when membrane potential decreases (depolarization), the driving force for ATP synthesis diminishes, reducing the cell’s capacity to generate energy efficiently. This can occur when proton leak increases—essentially, when the membrane becomes more permeable to protons that bypass ATP synthase, dissipating the gradient without producing ATP. The result is a decrease in the coupling efficiency between substrate oxidation and ATP synthesis.

Alterations in Membrane Lipid Composition

The lipid composition of mitochondrial membranes is exquisitely sensitive to metabolic conditions, and chronically elevated insulin significantly alters this composition in ways that compromise membrane function. Hyperinsulinemia is associated with increased accumulation of certain lipid species, particularly ceramides and diacylglycerols, within mitochondrial membranes.

Ceramides, a class of sphingolipids, have emerged as critical mediators of insulin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. These lipids can intercalate into mitochondrial membranes, altering membrane fluidity and disrupting the organization of respiratory chain supercomplexes. The formation of these supercomplexes—organized assemblies of electron transport chain components—is crucial for efficient electron transfer and energy production. When ceramides disrupt these structures, electron transport becomes less efficient, and reactive oxygen species production increases.

Furthermore, elevated insulin promotes lipogenesis and can lead to ectopic lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissues, a phenomenon known as lipotoxicity. When excess lipids accumulate in and around mitochondria, they interfere with mitochondrial membrane integrity and function. Cardiolipin, the signature phospholipid of mitochondrial membranes, may become oxidized or its synthesis may be impaired, further compromising membrane structure and the function of membrane-embedded proteins.

Impaired Mitochondrial Dynamics and Quality Control

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that continuously undergo fusion and fission, processes that are essential for maintaining a healthy mitochondrial network and distributing mitochondrial contents. Elevated insulin levels interfere with these dynamics in several ways. Hyperinsulinemia has been shown to promote excessive mitochondrial fission, leading to fragmentation of the mitochondrial network. These smaller, fragmented mitochondria tend to be less efficient at energy production and more prone to producing reactive oxygen species.

The balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission is regulated by specific proteins, including mitofusins and dynamin-related protein 1. Chronic insulin elevation alters the expression and activity of these proteins, tipping the balance toward fragmentation. This fragmentation not only reduces energy efficiency but also impairs the cell’s ability to buffer metabolic stress through mitochondrial networking.

Additionally, hyperinsulinemia interferes with mitophagy, the selective autophagy of damaged mitochondria. This quality control mechanism normally removes dysfunctional mitochondria before they can cause cellular harm. When mitophagy is impaired, damaged mitochondria with compromised membranes accumulate, reducing overall mitochondrial quality and energy-generating capacity. These dysfunctional mitochondria with damaged membranes continue to consume resources while producing less ATP and more oxidative stress.

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Membrane Damage

Perhaps one of the most consequential effects of elevated insulin on mitochondrial membrane performance is the generation of oxidative stress. When hyperinsulinemia creates metabolic inflexibility—forcing cells to continue processing nutrients even when energy stores are replete—mitochondria become overburdened. This metabolic overload leads to increased electron leak from the respiratory chain and enhanced production of reactive oxygen species.

These reactive molecules attack the mitochondrial membrane itself, causing lipid peroxidation that damages membrane structure and alters its properties. Peroxidized lipids can form toxic aldehydes that further damage proteins and DNA. The inner mitochondrial membrane, with its high concentration of unsaturated fatty acids in cardiolipin, is particularly vulnerable to this oxidative damage.

Protein components of the electron transport chain embedded in the membrane are also susceptible to oxidative modification. When these proteins become oxidized, their function deteriorates, creating a positive feedback loop where impaired respiratory chain function generates even more reactive oxygen species. This oxidative stress also affects the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, a channel that can open under conditions of severe stress, leading to membrane permeabilization, loss of membrane potential, and potentially triggering cell death pathways.

Effects on Calcium Handling and Signaling

Mitochondrial membranes play crucial roles in cellular calcium homeostasis, and elevated insulin disrupts these functions. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter and associated regulatory proteins control calcium entry into mitochondria, while the sodium-calcium exchanger and permeability transition pore regulate calcium exit. Calcium influx into mitochondria normally stimulates energy production by activating key metabolic enzymes, coupling energy demand with supply.

However, chronic hyperinsulinemia alters mitochondrial calcium handling in ways that impair this coupling. Excessive calcium accumulation in mitochondria can occur, driven by altered membrane potential and changes in calcium handling proteins. This calcium overload sensitizes mitochondria to stress and can trigger opening of the permeability transition pore, causing membrane depolarization and swelling. The resulting loss of membrane integrity compromises energy production and can initiate cell death cascades.

Conversely, impaired calcium uptake into mitochondria uncouples energy demand from production, meaning that metabolic enzymes don’t receive appropriate activation signals even when cellular energy needs are high. This contributes to metabolic inflexibility, where cells struggle to ramp up energy production in response to increased demands.

Tissue-Specific Effects of Insulin on Mitochondrial Membrane Function

The impact of elevated insulin on mitochondrial membrane performance varies across different tissues, reflecting their distinct metabolic roles and mitochondrial characteristics.

Skeletal Muscle

Skeletal muscle is a major site of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and oxidative metabolism. In muscle, chronic hyperinsulinemia leads to reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity and impaired membrane function. Studies have shown that individuals with insulin resistance have lower mitochondrial content and reduced expression of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. The mitochondria that are present often show reduced membrane potential and impaired coupling of respiration to ATP synthesis.

This mitochondrial dysfunction in muscle creates a metabolic bottleneck. When muscle cells cannot efficiently oxidize nutrients, metabolic intermediates accumulate, including lipid species that further impair insulin signaling and mitochondrial function. This contributes to a vicious cycle where insulin resistance begets mitochondrial dysfunction, which further worsens insulin resistance.

Liver

In hepatocytes, elevated insulin profoundly affects mitochondrial membrane function with significant metabolic consequences. The liver must balance glucose production, storage, and utilization while also handling lipid metabolism. Hyperinsulinemia shifts hepatic metabolism toward lipogenesis while impairing fatty acid oxidation, leading to lipid accumulation that directly impacts mitochondrial membranes.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, strongly associated with hyperinsulinemia, is characterized by significant mitochondrial dysfunction. Hepatic mitochondria in this condition show structural abnormalities, including swelling and loss of cristae, indicating membrane damage. The membrane potential is often reduced, and oxidative stress is elevated. These changes impair the liver’s capacity for gluconeogenesis, lipid oxidation, and detoxification, contributing to progressive liver dysfunction.

Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue mitochondria, though less abundant than in muscle or liver, play important roles in adipocyte function and whole-body metabolism. Elevated insulin affects adipocyte mitochondrial function in complex ways. While insulin normally promotes adipocyte differentiation and mitochondrial biogenesis, chronic hyperinsulinemia can lead to dysfunctional adipose expansion characterized by adipocyte hypertrophy, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Adipocyte mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to impaired adipokine secretion, altered fatty acid metabolism, and inflammatory signaling that affects systemic metabolism. The mitochondrial membranes in dysfunctional adipocytes show increased oxidative damage and reduced respiratory capacity, impairing the tissue’s ability to appropriately store and release energy.

Pancreatic Beta Cells

Ironically, the very cells that secrete insulin are themselves vulnerable to the effects of chronic hyperinsulinemia. Pancreatic beta cells rely heavily on mitochondrial function to couple glucose sensing with insulin secretion. Elevated ambient insulin levels, whether from exogenous sources or from compensatory hypersecretion, can negatively affect beta cell mitochondrial function through autocrine and paracrine effects.

Beta cell mitochondrial dysfunction manifests as impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, reduced ATP production, and increased oxidative stress. Membrane potential becomes dysregulated, affecting the cell’s ability to appropriately sense and respond to glucose. This mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to beta cell exhaustion and failure, accelerating the progression from compensated hyperinsulinemia to overt diabetes.

Metabolic Inflexibility and Substrate Switching

One of the most important functional consequences of insulin-induced mitochondrial membrane dysfunction is metabolic inflexibility—the inability to appropriately switch between different fuel sources based on availability and demand. Healthy mitochondria can efficiently oxidize either glucose or fatty acids, switching between these substrates based on nutritional state and energy needs.

Chronic hyperinsulinemia impairs this flexibility by promoting continuous glucose oxidation while simultaneously reducing fatty acid oxidation capacity. The mitochondrial membrane adaptations that support efficient switching between substrates become compromised. This includes changes in the transport of substrates across mitochondrial membranes, alterations in the activity of metabolic enzymes that depend on membrane organization, and shifts in the expression of proteins involved in substrate oxidation.

This metabolic rigidity means that cells continue attempting to oxidize glucose even in nutrient-replete states when they should be oxidizing stored fats. The forced continuation of glucose oxidation in the context of high nutrient availability overloads mitochondrial capacity, generating oxidative stress and further damaging mitochondrial membranes. Meanwhile, the inability to efficiently oxidize fats leads to lipid accumulation, lipotoxicity, and additional membrane dysfunction.

The Role of Mitochondrial-Derived Peptides and Signaling

Recent research has revealed that mitochondria function not merely as energy producers but as sophisticated signaling organelles that communicate with the rest of the cell and even other tissues. Mitochondrial membranes are central to this signaling function, and their dysfunction under conditions of elevated insulin has widespread consequences.

Mitochondria produce peptides such as humanin and MOTS-c that have metabolic and protective effects. The production and release of these peptides depends on proper mitochondrial membrane function. When membranes are dysfunctional due to chronic hyperinsulinemia, the production or release of these beneficial peptides may be impaired, removing important protective signals.

Additionally, damaged mitochondrial membranes release danger-associated molecular patterns, including mitochondrial DNA and oxidized lipids, which activate inflammatory signaling pathways. This mitochondrial-derived inflammation contributes to systemic metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance, creating another reinforcing cycle of metabolic deterioration.

Aging, Insulin, and Mitochondrial Membrane Function

The intersection of aging, insulin signaling, and mitochondrial function represents a crucial area of research. Mitochondrial function naturally declines with age, with mitochondrial membranes becoming more oxidatively damaged and less efficient. Simultaneously, insulin sensitivity tends to decrease with aging, often accompanied by rising insulin levels.

These two processes interact in problematic ways. Age-related mitochondrial decline makes cells more vulnerable to the negative effects of elevated insulin, while chronic hyperinsulinemia accelerates mitochondrial aging. The accumulated damage to mitochondrial membranes over time—from both aging and metabolic stress—progressively reduces cellular energy capacity and resilience.

Some researchers suggest that hyperinsulinemia may actually accelerate aging through its effects on mitochondrial function. The chronic oxidative stress, impaired quality control, and reduced energy efficiency associated with insulin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction mirror and potentially accelerate age-related mitochondrial decline. This connection may partially explain why conditions characterized by hyperinsulinemia are associated with accelerated aging and age-related diseases.

Implications for Disease

The effects of elevated insulin on mitochondrial membrane energy performance have profound implications for a wide range of diseases beyond diabetes itself.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiac myocytes have exceptionally high energy demands and dense mitochondrial content. Mitochondrial dysfunction due to hyperinsulinemia contributes to cardiac metabolic inflexibility, where the heart loses its ability to efficiently utilize different fuel sources. This rigidity, combined with reduced ATP production capacity, impairs cardiac function and contributes to heart failure. The oxidative stress generated by dysfunctional cardiac mitochondria also promotes atherosclerosis and vascular dysfunction.

Neurodegenerative Diseases

The brain is highly energy-dependent, and neurons rely heavily on mitochondrial function. Emerging evidence links insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia to neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, sometimes referred to as “type 3 diabetes.” Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons, driven partly by impaired insulin signaling and elevated insulin levels, contributes to neuronal energy failure, oxidative stress, and protein aggregation characteristic of these diseases.

Cancer

The relationship between hyperinsulinemia, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cancer is complex. Many cancer cells exhibit altered mitochondrial metabolism, and elevated insulin levels may promote tumor growth through multiple mechanisms. Mitochondrial membrane dysfunction in cancer cells contributes to the metabolic reprogramming known as the Warburg effect, where cells rely more heavily on glycolysis despite oxygen availability. Hyperinsulinemia may support this metabolic shift while also providing proliferative and anti-apoptotic signals through insulin and insulin-like growth factor signaling.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

This common endocrine disorder is strongly associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Mitochondrial dysfunction in various tissues, including ovarian cells, contributes to the hormonal and metabolic features of this condition. Impaired mitochondrial membrane function affects steroidogenesis, oocyte quality, and systemic metabolism in affected individuals.

Potential Interventions and Therapeutic Strategies

Understanding how elevated insulin affects mitochondrial membrane function opens avenues for therapeutic intervention. Several approaches show promise for protecting or restoring mitochondrial membrane function in the context of hyperinsulinemia.

Lifestyle Interventions

Dietary approaches that reduce insulin levels can have profound benefits for mitochondrial function. Caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, and low-carbohydrate diets tend to lower insulin levels and improve mitochondrial membrane function. These interventions reduce the metabolic burden on mitochondria, decrease oxidative stress, and allow time for mitochondrial repair and quality control processes to operate effectively.

Exercise represents one of the most powerful interventions for improving mitochondrial function. Physical activity promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, enhances mitochondrial quality control, and improves insulin sensitivity, creating a beneficial cycle. Exercise also stimulates the production of proteins and signaling molecules that protect mitochondrial membranes from oxidative damage.

Pharmacological Approaches

Metformin, a first-line medication for type 2 diabetes, acts partly through effects on mitochondrial function. While it mildly inhibits Complex I of the electron transport chain, this effect appears to trigger beneficial adaptations that ultimately improve metabolic health and insulin sensitivity. The drug’s effects on reducing hyperinsulinemia likely contribute significantly to its mitochondrial benefits.

Newer therapeutic approaches target mitochondrial function more directly. Compounds that enhance mitochondrial biogenesis, reduce oxidative stress, or protect mitochondrial membranes are being investigated. These include mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, compounds that modulate mitochondrial dynamics, and agents that enhance mitophagy.

SGLT2 inhibitors, which reduce blood glucose levels through a kidney-based mechanism independent of insulin, have shown benefits for mitochondrial function, likely partly through their insulin-lowering effects. Similarly, GLP-1 receptor agonists, which enhance insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner while promoting weight loss, may benefit mitochondrial function through multiple pathways including reduced hyperinsulinemia.

Nutritional Compounds

Certain nutrients and bioactive compounds show promise for protecting mitochondrial membrane function. Coenzyme Q10, a component of the electron transport chain, can support mitochondrial respiration and may have antioxidant effects. Alpha-lipoic acid acts as an antioxidant and can improve mitochondrial function. Omega-3 fatty acids can be incorporated into mitochondrial membranes, potentially improving membrane fluidity and function.

Compounds that support cardiolipin synthesis or protect it from oxidative damage may be particularly valuable, given cardiolipin’s central role in mitochondrial membrane structure and function. Similarly, compounds that reduce ceramide accumulation might protect against insulin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction.

Future Directions and Research Needs

While our understanding of how elevated insulin affects mitochondrial membrane energy performance has advanced considerably, many questions remain. Future research needs to more precisely characterize the dose-response relationship between insulin levels and mitochondrial dysfunction, determine critical windows for intervention, and identify which aspects of mitochondrial dysfunction are reversible.

The heterogeneity of mitochondrial responses across different tissues and individuals needs further investigation. Why are some people more resilient to the mitochondrial effects of hyperinsulinemia? What genetic and environmental factors modify these responses? Understanding this variation could enable more personalized interventions.

The development of better tools for assessing mitochondrial membrane function in living humans would enable more precise diagnosis and monitoring. Current methods often require invasive biopsies or provide only indirect measurements. Non-invasive imaging approaches and biomarkers that reflect mitochondrial membrane health could transform clinical care.

Research into the temporal dynamics of mitochondrial dysfunction is also needed. Does mitochondrial dysfunction precede and drive hyperinsulinemia, or vice versa? Is there a tipping point beyond which mitochondrial damage becomes self-perpetuating? Understanding these dynamics could identify optimal intervention points.

Conclusion

The relationship between elevated insulin and mitochondrial membrane energy performance represents a critical intersection in human metabolism and health. Chronic hyperinsulinemia disrupts mitochondrial membrane structure and function through multiple mechanisms, including alterations in membrane potential, changes in lipid composition, impaired quality control, oxidative stress, and dysregulated calcium handling. These effects manifest differently across tissues but consistently result in reduced energy efficiency, metabolic inflexibility, and cellular dysfunction.

The consequences extend far beyond energy production itself. Insulin-induced mitochondrial membrane dysfunction contributes to a vicious cycle of metabolic deterioration, involving oxidative stress, inflammation, and progressive insulin resistance. This dysfunction underlies or contributes to numerous diseases, from type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative conditions and cancer.

However, this understanding also provides hope. The mitochondrion is remarkably adaptable, and many aspects of insulin-induced dysfunction appear reversible with appropriate interventions. Lifestyle approaches that lower insulin levels—including dietary modifications, fasting strategies, and exercise—can substantially improve mitochondrial membrane function. Pharmacological interventions are evolving to more specifically target mitochondrial dysfunction while addressing hyperinsulinemia.

Be First to Comment