Executive Summary

Budget deficits have become a defining characteristic of modern economic governance, with even the world’s most powerful economies struggling to balance their books. As of 2024, the fiscal landscape reveals a troubling reality: nations across the globe are spending significantly more than they collect in revenue, creating long-term challenges for economic stability, debt servicing, and future growth. This comprehensive analysis examines the budget deficits of the world’s ten largest economies, exploring their causes, implications, and the difficult policy choices that lie ahead.

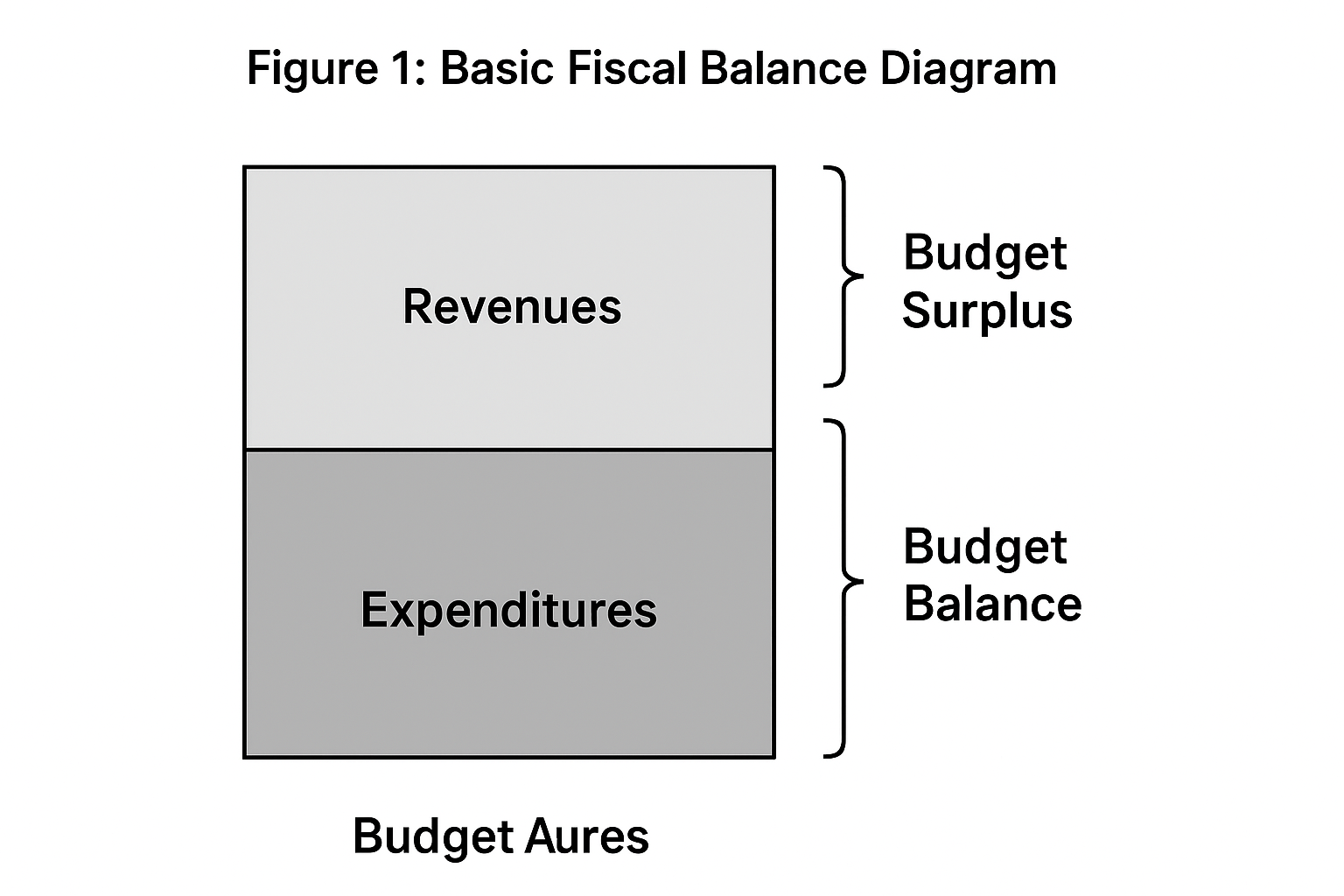

Introduction: Understanding Budget Deficits in the Modern Economy

A budget deficit occurs when a government’s expenditures exceed its revenues over a given period, forcing the nation to borrow funds to cover the shortfall. While temporary deficits can serve legitimate purposes—stimulating demand during economic downturns, funding critical infrastructure, or responding to emergencies—persistent structural deficits raise concerns about long-term fiscal sustainability.

The metric commonly used to assess the severity of a deficit is its percentage of Gross Domestic Product. This ratio allows for meaningful comparisons between economies of different sizes and provides insight into whether a nation’s deficit is manageable relative to its economic capacity. Countries with deficits consistently exceeding three to four percent of GDP face increasing pressure from financial markets, higher borrowing costs, and reduced fiscal flexibility for future crises.

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically altered the global fiscal landscape. Governments worldwide deployed unprecedented stimulus measures, providing direct payments to citizens, supporting businesses, and bolstering healthcare systems. While these interventions prevented economic collapse, they left behind a legacy of elevated debt levels and ongoing deficits. Four years later, many nations have struggled to return to pre-pandemic fiscal discipline, as new structural demands—from defense spending to climate initiatives—compete for limited resources.

The Top 10 Largest Economies by GDP (2024)

Before examining deficits, it is essential to identify the world’s largest economies. Based on nominal GDP data from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, the top ten economies in 2024 are:

- United States – $28.78 trillion

- China – $18.53 trillion

- Germany – $4.59 trillion

- Japan – $4.02 trillion

- India – $3.94 trillion

- United Kingdom – $3.34 trillion

- France – $3.13 trillion

- Italy – $2.33 trillion

- Brazil – $2.33 trillion

- Canada – $2.24 trillion

These nations collectively represent the majority of global economic output and exert enormous influence over international trade, finance, and monetary policy. Their fiscal health—or lack thereof—has profound implications for the global economy.

Detailed Analysis of Budget Deficits Among the World’s Largest Economies

1. United States: The Deficit Superpower

Budget Deficit: 6.0-6.5% of GDP (2024)

The United States maintains the dubious distinction of having the largest absolute budget deficit among major developed nations. The federal government recorded a deficit of approximately $1.8 trillion in fiscal year 2024, equivalent to 6.4 percent of GDP. This marks a continuation of elevated deficits that have persisted since the Great Recession, interrupted only briefly by the budget surpluses of the late 1990s.

Several factors drive America’s persistent fiscal imbalance. On the revenue side, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act permanently reduced corporate and individual income tax rates, constraining government revenues even as the economy grew. Meanwhile, mandatory spending programs continue their inexorable rise. Social Security expenditures are climbing as the Baby Boomer generation ages into retirement, while Medicare and Medicaid costs surge with both demographic shifts and rising healthcare prices.

Perhaps most concerning is the explosion in interest payments on the national debt. With interest rates rising from near-zero levels to above 5 percent between 2022 and 2023, the federal government’s debt service costs have skyrocketed. Net interest payments reached $949 billion in 2024, an increase of 34 percent over the previous year. The Congressional Budget Office projects these costs will climb to $1.6 trillion by 2034, consuming an ever-larger share of the federal budget and crowding out other priorities.

The political economy of deficit reduction in the United States is particularly challenging. The two major political parties disagree fundamentally about solutions, with Republicans emphasizing spending cuts (except for defense and entitlement programs popular with their base) and Democrats prioritizing revenue increases through higher taxes on corporations and wealthy individuals. This ideological gridlock has prevented meaningful fiscal reform for decades.

Despite these massive deficits, the United States enjoys unique advantages that allow it to sustain high borrowing levels. The dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency creates constant demand for U.S. Treasury securities, keeping borrowing costs lower than they would be otherwise. Additionally, the size and liquidity of U.S. financial markets make Treasury bonds the global standard for safe-haven assets. However, economists debate whether these advantages can persist indefinitely if deficits remain structurally high.

2. China: Hidden Depths in the World’s Second-Largest Economy

Budget Deficit: 7.4-8.6% of GDP (2024)

China’s fiscal position is more complex and potentially more concerning than commonly understood. While official central government deficit figures have historically appeared modest, a comprehensive assessment that includes provincial, municipal, and local government borrowing—much of it conducted through off-balance-sheet vehicles—reveals a deficit approaching or exceeding 8 percent of GDP.

China’s fiscal challenges stem from several structural factors. The country’s property sector, which has driven much of China’s economic growth over the past two decades, is experiencing a severe downturn. Major developers have defaulted on debt obligations, local governments have seen sharp declines in land sales revenue (a critical funding source), and household wealth effects from falling property values have dampened consumption.

Local government financing vehicles, entities created to circumvent borrowing restrictions on provincial and municipal governments, have accumulated enormous debts. These implicit government liabilities do not appear in official deficit figures but represent genuine fiscal obligations that central authorities may ultimately need to honor to prevent financial instability.

Furthermore, China’s demographic challenge is intensifying. The working-age population is shrinking while the elderly population expands rapidly, straining pension systems and healthcare spending while reducing the tax base. Unlike many developed nations that had decades to build social safety nets before facing demographic decline, China confronts aging before becoming truly affluent—a situation demographers describe as “growing old before growing rich.”

The Chinese government has deployed fiscal stimulus to support growth targets, including infrastructure investment and subsidies for strategic industries like semiconductors and electric vehicles. While these investments may yield long-term economic benefits, they widen near-term deficits. Beijing’s traditional reliance on high savings rates and financial repression to absorb government debt may face limits as households become more risk-aware and seek to diversify savings internationally.

3. France: The Perils of Continental Social Democracy

Budget Deficit: 5.3-6.0% of GDP (2024)

France exemplifies the fiscal pressures facing European social democracies in the 21st century. The country’s budget deficit for 2024 is projected at approximately 5.3 to 6 percent of GDP, well above the European Union’s three percent threshold and marking a deterioration from pre-pandemic levels.

French fiscal challenges are rooted in the generous social model that defines the nation’s political economy. France maintains one of the world’s most comprehensive welfare states, with extensive unemployment benefits, universal healthcare, subsidized childcare, and a retirement system that traditionally allowed workers to exit the labor force relatively early. These programs command broad public support but impose enormous fiscal costs, with government spending representing approximately 58 percent of GDP—among the highest ratios in the developed world.

Efforts to reform this model have proven politically treacherous. President Emmanuel Macron’s attempts to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64 sparked massive protests and political backlash, despite France’s retirement age being lower than most peer nations. Labor market reforms aimed at increasing flexibility and encouraging employment have similarly faced fierce resistance from unions and left-wing parties.

On the revenue side, France already has one of the highest tax burdens in the OECD, limiting room for further increases. High taxes on labor and capital have contributed to brain drain, with successful entrepreneurs and highly skilled professionals relocating to lower-tax jurisdictions like Switzerland, the United Kingdom, or the United States. This flight reduces the tax base and reinforces concerns about France’s long-term competitiveness.

The European Union’s renewed enforcement of fiscal rules, suspended during the pandemic, adds external pressure on France to reduce its deficit. The excessive deficit procedure could require France to implement structural fiscal consolidation of at least 0.5 percentage points per year beginning in 2025, potentially constraining economic growth at a time when the French economy already faces headwinds from global trade tensions and energy transition costs.

4. Italy: A Chronic Case of Fiscal Dysfunction

Budget Deficit: 3.4-6.3% of GDP (2024)

Italy’s fiscal situation has improved more than expected in 2024, with the annual deficit falling to 3.4 percent of GDP from 7.2 percent in 2023. However, this improvement masks deeper structural problems that have plagued Italian public finances for decades.

Italy carries the second-highest debt-to-GDP ratio in the European Union after Greece, approaching 140 percent. This massive debt stock makes Italy acutely vulnerable to changes in interest rates and market sentiment. The country’s borrowing costs spiked in 2022 and 2023 as the European Central Bank raised interest rates, significantly increasing debt service expenses.

The recent deficit improvement stems partly from fiscal restraint but also from temporary factors unlikely to persist. The Italian government allowed the “Superbonus” construction tax credit program—a pandemic-era stimulus that subsidized home renovations at extraordinarily generous rates—to expire. This program had proven vastly more expensive than anticipated, adding more than one percent of GDP to the deficit. Its termination provided immediate fiscal relief but eliminated an economic stimulus at a time when Italian growth remains anemic.

Italy’s fundamental problem is persistently weak economic growth. Real GDP expanded only 0.7 percent in 2024, and the country has experienced near-stagnant growth for the past two decades. Without robust economic expansion, reducing the debt burden through growth becomes impossible, leaving only austerity or default as options. Low growth also makes deficit reduction more difficult, as weak economic activity depresses tax revenues while maintaining pressure for social spending.

The Italian political system compounds these fiscal challenges. Governments frequently change, often lasting less than two years, making sustained reform efforts difficult. Coalition politics favor spending commitments to satisfy various constituent groups rather than tough choices about fiscal consolidation. This dynamic has produced a pattern of incremental adjustments rather than comprehensive reform.

Italy’s fiscal situation creates systemic risks for the eurozone. As the third-largest economy in the currency union, Italian financial instability could trigger broader contagion. The European Central Bank’s Transmission Protection Instrument, designed to prevent excessive borrowing cost spreads for compliant member states, requires Italy to maintain fiscal discipline and implement reforms—conditionality that adds political complexity to already difficult fiscal choices.

5. United Kingdom: Post-Brexit Fiscal Realities

Budget Deficit: 4.3-5.5% of GDP (2024)

The United Kingdom recorded a government deficit of approximately 5.5 percent of GDP in 2024 according to IMF estimates, though this has improved somewhat from pandemic highs. British fiscal policy faces unique challenges stemming from the aftermath of Brexit, an aging population, and the imperative to rebuild public services after years of austerity.

Brexit has imposed both direct and indirect costs on UK public finances. The loss of EU budget contributions provides minimal relief compared to reduced economic dynamism from trade friction, decreased foreign investment, and slower productivity growth. The Office for Budget Responsibility has consistently estimated that Brexit will reduce long-term GDP by approximately 4 percent relative to remaining in the EU, translating to permanently lower tax revenues.

The UK’s National Health Service represents a particular fiscal pressure point. The NHS enjoys enormous public affection but faces mounting challenges from demographic aging, advances in expensive medical technologies, and workforce shortages exacerbated by Brexit’s end to free movement of EU healthcare workers. Successive governments have struggled to adequately fund the NHS while maintaining fiscal discipline, resulting in deteriorating service quality and growing waiting lists.

The Conservative government’s “austerity” programs following the 2008 financial crisis succeeded in reducing the deficit from peak levels above 10 percent of GDP but left lasting scars on public services and infrastructure. The post-2024 Labour government faces pressure to increase public investment and restore services while also confronting bond market vigilance about fiscal credibility—as demonstrated by the market turmoil that followed the brief Truss government’s unfunded tax cut proposals in 2022.

Interest payments on UK government debt have risen sharply as the Bank of England raised interest rates to combat inflation. This reduces fiscal space for other priorities and makes deficit reduction more challenging. The UK’s decision to issue a significant portion of its debt at variable rates and to use inflation-linked bonds has magnified the impact of rising rates and prices on debt service costs.

6. Japan: The Deficit Paradox

Budget Deficit: 3.0-6.1% of GDP (2024)

Japan presents a fascinating paradox in public finance. The country maintains a budget deficit of approximately 6 percent of GDP while carrying a government debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 260 percent—by far the highest in the developed world. Yet Japanese government bond yields remain extraordinarily low, and the country faces no immediate fiscal crisis.

This apparent defiance of fiscal gravity stems from several unique factors. Japan maintains a high domestic savings rate, and Japanese investors display a strong home bias, readily absorbing government debt issues. The Bank of Japan owns more than half of all outstanding government bonds, having purchased them through quantitative easing programs. This monetization of debt, while technically distinct from direct central bank financing of government deficits, effectively removes much of the debt from private markets.

Japan’s fiscal challenges are intimately connected to its demographic crisis. The country has the world’s oldest population and a declining workforce. This creates a scissors effect on public finances: rising pension and healthcare costs meet shrinking tax revenues from a smaller working-age population. Japan’s fertility rate of approximately 1.3 children per woman—well below the replacement rate of 2.1—ensures this demographic pressure will intensify.

For decades, Japanese governments have attempted to stimulate economic growth through fiscal spending, particularly infrastructure investment. These efforts have yielded disappointing results, with nominal GDP remaining essentially unchanged since the late 1990s. Persistent deflation has exacerbated debt burdens by preventing inflation from eroding the real value of government obligations.

Recently, Japan has experienced modest inflation for the first time in decades, partly due to global supply chain disruptions and commodity price increases. This development, if sustained, could actually improve Japan’s fiscal trajectory by boosting nominal GDP growth and tax revenues while reducing the real burden of existing debt. However, it also complicates the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy, as normalizing interest rates after decades of ultra-low rates could dramatically increase government debt service costs.

7. India: Deficits in a Developing Giant

Budget Deficit: 6.9-7.8% of GDP (2024)

India’s fiscal deficit of approximately 7 percent of GDP reflects the challenges of financing development priorities in a large, lower-middle-income country with substantial infrastructure needs and social protection gaps. Unlike developed nations where deficits primarily fund existing entitlement programs, India’s borrowing finances a mix of development investment and subsidies.

The Indian government provides extensive subsidies for food, fertilizer, and fuel aimed at protecting hundreds of millions of poor and lower-middle-class citizens from price volatility. While these programs serve important social functions, they impose significant fiscal costs. Food security programs alone cost billions of dollars annually, distributing subsidized grain to more than 800 million people.

Infrastructure investment represents another major driver of India’s deficit. The country requires enormous investments in roads, railways, ports, power generation and distribution, and urban water and sanitation systems to support continued economic growth and rising living standards. The government’s emphasis on capital expenditure as a growth driver has increased the deficit in the near term, though supporters argue these investments will generate future economic returns that improve long-term fiscal sustainability.

Tax collection challenges constrain India’s revenue side. Despite recent improvements, tax evasion remains widespread, particularly in the informal sector that employs the majority of the Indian workforce. The goods and services tax, introduced in 2017, has increased efficiency but collection still falls short of potential. Income taxes are paid by a relatively small proportion of the population, limiting the tax base.

India’s demographic profile provides both opportunities and challenges. The country has a young population with a median age under 30, offering a potential demographic dividend if these workers can be productively employed. However, job creation has lagged population growth, and providing education, healthcare, and economic opportunities for hundreds of millions of young people will require sustained public investment.

8. Germany: The Reluctant Deficit Country

Budget Deficit: 2.5% of GDP (2024)

Germany’s fiscal situation represents a striking departure from its historical identity as the paragon of budget discipline. The country that long championed the “schwarze Null” (black zero, or balanced budget) now runs a deficit of approximately 2.5 percent of GDP—modest by international standards but psychologically significant for a nation that made fiscal conservatism a core political value.

Several factors have driven Germany’s shift from surplus to deficit. Energy costs soared following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent disruption of natural gas supplies that German industry depended upon. The government deployed substantial fiscal resources to cushion households and businesses from spiking energy prices, widening the deficit. Additionally, Germany has belatedly recognized the need for greater defense spending in response to changed European security dynamics, committing to reach NATO’s two percent of GDP target.

Germany’s constitutional debt brake, enshrined in the Basic Law, limits structural deficits to 0.35 percent of GDP for the federal government under normal circumstances. This rule has constrained fiscal policy and generated political tensions, as some argue it prevents necessary public investment in infrastructure, digitalization, and climate transition. The debt brake can be suspended in emergencies, as occurred during the pandemic, but reinstating it has forced difficult budget choices.

Infrastructure decay poses a growing challenge. Germany’s transportation networks, built during the post-war boom, require extensive renovation. Bridges, railways, and roads have suffered from decades of deferred maintenance. The country’s famous Autobahn system shows signs of neglect, while Deutsche Bahn, the state railway, faces reliability problems. Addressing these deficiencies while observing fiscal rules creates policy dilemmas.

Germany’s export-oriented manufacturing sector, particularly its automotive industry, faces structural challenges from the transition to electric vehicles and competition from Chinese manufacturers. If these industries decline, tax revenues could suffer while pressure for government support increases. The country’s relatively closed immigration policies have limited the potential for demographic renewal through immigration, though this has begun to change.

Despite these challenges, Germany retains substantial fiscal capacity. Government debt at approximately 60 percent of GDP is manageable by international standards. The country benefits from negative real interest rates on much of its debt and from the euro’s strength as a reserve currency. If political will coalesced around fiscal expansion, Germany could deploy significant resources while maintaining market confidence.

9. Brazil: Tropical Fiscal Turbulence

Budget Deficit: 5.8-8.5% of GDP (2024)

Brazil’s fiscal position reflects the volatile politics and economic cycles characteristic of Latin America’s largest nation. The budget deficit reached approximately 8.5 percent of GDP in 2024 according to some measures, though official government figures show primary deficits (excluding interest payments) of around 5.8 percent.

Brazil’s fiscal challenges are deeply rooted in its political economy. The constitution mandates numerous spending commitments, including generous public sector pensions, minimum wage adjustments linked to inflation, and healthcare and education spending floors. These mandatory expenditures consume the vast majority of the budget, leaving limited room for discretionary spending or fiscal adjustment. Attempts to reform these constitutional obligations face formidable political and legal obstacles.

Interest payments on government debt impose enormous costs. Brazil’s debt servicing consumes a larger share of the budget than in virtually any other major economy, reflecting both the size of the debt stock and elevated interest rates. The central bank has maintained relatively high rates to control inflation and defend the currency, but these rates directly increase fiscal costs through higher debt service.

Brazil’s tax system is extraordinarily complex and inefficient, with multiple overlapping taxes at federal, state, and municipal levels. This complexity increases compliance costs, encourages evasion, and reduces economic efficiency. Tax reform efforts have made incremental progress but comprehensive simplification remains elusive due to competing interests among different government levels and economic sectors.

Commodity dependence creates fiscal volatility. Brazil’s government revenues fluctuate with global prices for soybeans, iron ore, oil, and other commodities that dominate exports. This makes fiscal planning difficult and can trigger boom-bust cycles in public spending. The country lacks robust fiscal buffers or sovereign wealth funds to smooth these fluctuations.

Political instability compounds fiscal problems. Presidential impeachments, corruption scandals, and sharp ideological shifts between governments have prevented consistent long-term fiscal strategies. The Bolsonaro and Lula governments have pursued dramatically different policies, creating uncertainty for investors and complicating efforts to build consensus around fiscal reforms.

10. Canada: Resource Wealth Meets Fiscal Pressure

Budget Deficit: 0.5-0.8% of GDP (2024)

Canada maintains one of the smallest deficits among major economies at approximately 0.5 to 0.8 percent of GDP, reflecting both substantial resource revenues and relatively strong fiscal institutions. However, the country faces mounting fiscal pressures that may challenge this enviable position.

Canadian provinces carry significant debt burdens separate from federal obligations, with some—particularly Quebec and Ontario—facing serious fiscal challenges. When provincial and federal deficits are consolidated, Canada’s overall fiscal position appears less favorable than federal figures alone suggest. Healthcare, primarily a provincial responsibility, imposes growing costs as the population ages and medical technology advances.

The country’s enormous geographic size and sparse population density create unique infrastructure challenges. Maintaining transportation networks, telecommunications, and public services across vast distances is inherently expensive. Climate change threatens existing infrastructure through permafrost thaw in the North, increased flooding, and extreme weather events, requiring costly adaptation investments.

Canada’s economy remains heavily dependent on natural resources, particularly oil and gas exports from Alberta. The global energy transition poses a long-term threat to these revenues, potentially creating fiscal gaps that other sectors cannot easily fill. The political challenge lies in managing this transition while supporting workers and communities economically dependent on fossil fuel industries.

Housing affordability has become a political crisis, particularly in major cities like Vancouver and Toronto where prices have soared. Government interventions to increase supply and improve affordability require public investment, adding to spending pressures. Immigration, which Canada has increased to address labor shortages and demographic aging, necessitates investments in settlement services, infrastructure, and public services.

Indigenous reconciliation represents both a moral imperative and a fiscal commitment. Addressing historical injustices, improving living conditions in Indigenous communities, settling land claims, and investing in economic development all require sustained public resources. While these investments are necessary, they add to competing demands on the federal budget.

Common Themes and Drivers Across All Economies

Several factors unite the fiscal challenges facing the world’s largest economies, transcending differences in political systems, development levels, and economic structures:

Demographic Aging: Virtually all major economies face aging populations, with declining ratios of working-age adults to retirees. This creates a fiscal scissors effect, as pension and healthcare costs rise while the tax base shrinks. Japan, Germany, and Italy face the most acute challenges, but even younger populations like India’s will age rapidly in coming decades.

Rising Healthcare Costs: Medical spending consistently outpaces GDP growth across developed nations. Technological advances enable new treatments—often extremely expensive—while demographic aging increases the population requiring care. No country has solved the puzzle of containing healthcare costs without rationing or compromising quality.

Interest Rate Normalization: After more than a decade of near-zero or negative interest rates, central banks worldwide have raised rates to combat inflation. This increases government borrowing costs dramatically, particularly affecting highly indebted nations. Countries that borrowed heavily at low rates now face a refinancing cliff as this debt matures.

Climate Transition Costs: The shift to net-zero emissions requires enormous investments in renewable energy, grid infrastructure, transportation electrification, and industrial transformation. While these investments may generate long-term economic benefits, they impose near-term fiscal costs. Additionally, adaptation to climate change already underway requires spending on coastal protection, water management, and disaster response.

Defense and Security: Geopolitical tensions have prompted increased military spending across many nations. European countries are expanding defense budgets in response to Russian aggression, while Indo-Pacific nations bolster capabilities amid Chinese assertiveness. The United States maintains global military commitments that consume a significant portion of its budget.

Political Polarization: Many democracies face deep ideological divisions that prevent consensus on fiscal policy. Tax increases and spending cuts both encounter fierce opposition, making deficit reduction politically treacherous. Short-term electoral cycles incentivize politicians to defer difficult choices, allowing problems to compound.

Economic and Political Consequences of Persistent Deficits

Large, sustained budget deficits generate multiple risks and challenges that policymakers must navigate:

Crowding Out: Government borrowing absorbs savings that could otherwise finance private investment. This can raise interest rates throughout the economy, making business expansion and home purchases more expensive. While empirical evidence for crowding out varies depending on circumstances, it remains a theoretical concern, particularly when deficits occur during economic expansions.

Debt Sustainability Questions: As debt-to-GDP ratios climb, investors may question whether governments can service obligations without resorting to inflation or default. This can trigger rising risk premiums, making borrowing more expensive and potentially creating self-fulfilling crises. Market confidence can evaporate suddenly, as demonstrated by sovereign debt crises in Greece, Argentina, and other nations.

Reduced Fiscal Space: High deficits and debt constrain governments’ ability to respond to future crises. When the next recession, pandemic, or financial emergency strikes, highly indebted nations may find themselves unable to deploy adequate fiscal stimulus without risking market confidence. This vulnerability could make future downturns deeper and more prolonged.

Intergenerational Equity: Persistent deficits effectively transfer costs to future generations, who must service debt incurred to finance current consumption. While borrowing for productive investments that benefit the future can be justified, financing ongoing programs through debt raises ethical questions about fairness between generations.

Political Economy Distortions: Deficit financing allows governments to provide services without fully taxing citizens to pay for them, obscuring the true cost of government. This can lead to inefficient political outcomes, with voters demanding spending increases or tax cuts without appreciating budgetary trade-offs. It also advantages current politicians who deliver benefits while successors must address the fiscal consequences.

Policy Options and Reform Pathways

Addressing structural budget deficits requires difficult policy choices on both revenue and expenditure sides, often encountering fierce political resistance:

Revenue Enhancement: Governments can raise taxes, improve collection, or broaden the tax base. Options include higher income tax rates on wealthy individuals and corporations, wealth taxes, carbon taxes, consumption tax increases, and digital services taxes. However, tax increases face opposition from affected groups and may have economic costs through reduced incentives for work, investment, or entrepreneurship.

Entitlement Reform: Modifying pension and healthcare programs offers substantial savings potential given their large share of budgets. Reforms might include raising retirement ages, means-testing benefits, adjusting cost-of-living formulas, encouraging private retirement savings, or restructuring healthcare delivery. Such changes face resistance from beneficiaries and create political risks.

Discretionary Spending Cuts: Reducing spending on defense, infrastructure, education, or other discretionary programs can narrow deficits. However, many developed countries have already constrained these budgets through past austerity, and further cuts may damage economic growth or national security. Additionally, discretionary spending is generally smaller than mandatory programs.

Economic Growth: Accelerating economic growth expands the tax base and reduces the deficit-to-GDP ratio mechanically. Growth-enhancing reforms might include infrastructure investment, education improvements, regulatory streamlining, trade liberalization, or innovation support. However, growth effects are uncertain and often materialize slowly, while political consensus on pro-growth policies can be elusive.

Inflation: Moderate inflation erodes the real value of nominal government debt, providing hidden fiscal relief. Some economists argue that allowing inflation slightly above central bank targets would ease debt burdens without triggering the catastrophic effects of hyperinflation. However, this approach risks de-anchoring inflation expectations and imposing hidden taxes on savers and fixed-income recipients.

Fiscal Rules and Institutions: Constitutional or legal constraints on deficits and debt can impose discipline, as with Germany’s debt brake or the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact. Independent fiscal councils can provide objective analysis and hold governments accountable. However, rules may prove too rigid during crises or be circumvented through creative accounting.

Structural Reforms: Broader economic reforms—such as labor market flexibility, pension system restructuring, or tax simplification—can improve long-term fiscal sustainability even without immediately reducing deficits. These reforms often face intense political opposition from incumbent interests but may be necessary for durable solutions.

Conclusion: The Fiscal Reckoning

The world’s largest economies face a common fiscal reality: expenditures significantly exceed revenues, creating deficits that expand government debt and constrain future policy options. While the specific circumstances vary—from Japan’s demographic crisis to America’s healthcare costs to Brazil’s interest burden—the underlying challenge is universal. Governments must either reduce spending, increase revenues, accelerate growth, or accept continuing debt accumulation with its attendant risks.

The post-pandemic period has revealed the limits of fiscal forbearance. Central banks’ normalization of interest rates has ended the era of free money, making deficits genuinely costly again. Geopolitical instability demands defense investments while climate change requires enormous transition spending. Demographic aging is no longer a distant threat but a present reality imposing immediate costs. The easy solutions have been exhausted.

What comes next depends on political choices that democracies have thus far proven reluctant to make. Will voters accept higher taxes to finance the public services they demand? Will beneficiaries of pensions and healthcare accept reforms that reduce future benefits? Will politicians risk electoral backlash by implementing necessary but unpopular policies? Will societies address the deeper structural problems—inequality, slow productivity growth, political polarization—that underlie fiscal dysfunction?

History offers both encouraging and cautionary lessons. Some countries have successfully consolidated public finances through determined reform programs, often following crises that made the status quo untenable. Canada in the 1990s, Sweden in the early 1990s, and several post-2008 European nations demonstrated that fiscal adjustment is possible, though typically requiring broad political consensus and favorable economic conditions.

However, history also shows that countries frequently postpone necessary adjustments until forced by crisis. Sovereign defaults, hyperinflation, austerity imposed by international creditors, and economic stagnation have all resulted from fiscal mismanagement. The question facing today’s major economies is whether they will choose reform or wait for crises to force their hand.

The stakes could not be higher. In an interconnected global economy, fiscal crises in major nations can trigger contagion, disrupt financial markets, and destabilize the international monetary system. The fiscal health of the world’s largest economies is not merely a domestic concern—it is a global public good requiring vigilant stewardship and, when necessary, courageous reform.

As we move deeper into the 21st century, budget deficits will likely remain a defining challenge for democratic governance and economic management. The nations that successfully navigate this challenge will emerge stronger and more resilient. Those that fail risk prolonged stagnation, diminished influence, and reduced prosperity for their citizens. The fiscal reckonings ahead will test the capacity of democratic institutions to make difficult long-term choices in the face of short-term political pressures. The outcome remains uncertain, but the urgency is clear.

Be First to Comment