Water is so familiar that we rarely pause to consider its remarkable nature. We drink it, bathe in it, and depend upon it for our survival. Yet this simple molecule holds within it a story that spans the entire history of the universe, from the first moments after the Big Bang to the formation of our planet and the emergence of life itself. Understanding what water is made of and where it comes from takes us on a journey through chemistry, physics, astronomy, and planetary science.

Part I: The Molecular Anatomy of Water

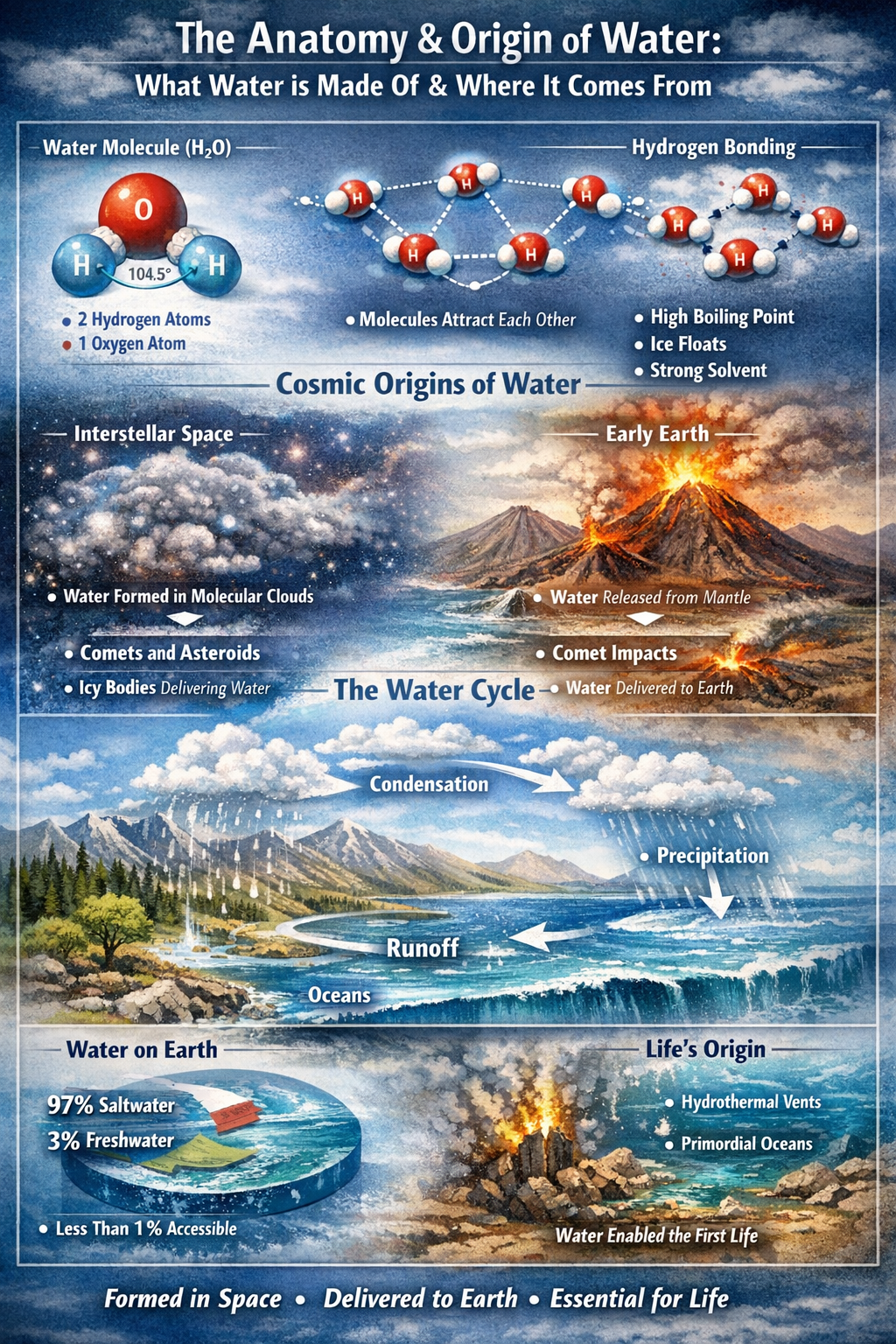

The Basic Structure: Two Hydrogens, One Oxygen

At its most fundamental level, water is composed of three atoms: two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, bonded together in the familiar chemical formula H₂O. This simple arrangement belies an extraordinary complexity in water’s behavior and properties.

Each hydrogen atom consists of a single proton in its nucleus, orbited by a single electron. Oxygen, by contrast, has eight protons and typically eight neutrons in its nucleus, with eight electrons arranged in two shells around it. When these atoms come together to form water, they do so through covalent bonds, where electrons are shared between atoms.

The Covalent Bonds: Sharing Electrons

The oxygen atom in a water molecule has six electrons in its outer shell, but it needs eight to achieve stability (following the octet rule that governs much of chemistry). Each hydrogen atom has one electron but needs two for stability. The solution is elegant: the oxygen atom shares electrons with two hydrogen atoms, forming two covalent bonds. Each hydrogen atom contributes its single electron to share with oxygen, while oxygen shares one of its electrons with each hydrogen.

This sharing creates a stable molecule, but the electrons are not shared equally. Oxygen is much more electronegative than hydrogen, meaning it has a stronger pull on the shared electrons. As a result, the electrons spend more time near the oxygen atom than near the hydrogen atoms. This unequal sharing creates what chemists call a polar covalent bond.

The Bent Geometry: Why Water Isn’t Linear

If you were to examine the three-dimensional structure of a water molecule, you would not find the three atoms arranged in a straight line. Instead, the molecule has a distinctive bent shape, with an angle of approximately 104.5 degrees between the two hydrogen-oxygen bonds. This angle is slightly less than the ideal tetrahedral angle of 109.5 degrees.

The bent shape arises from the arrangement of electron pairs around the oxygen atom. Oxygen has four pairs of electrons in its outer shell: two pairs involved in bonding with the hydrogen atoms, and two “lone pairs” that are not involved in bonding. These four electron pairs repel each other and arrange themselves in a roughly tetrahedral geometry to minimize repulsion. However, the lone pairs exert slightly more repulsion than bonding pairs, compressing the hydrogen-oxygen-hydrogen angle to 104.5 degrees.

This bent geometry is crucial to water’s properties. If water were linear, it would be a nonpolar molecule despite the polar bonds, because the two polarities would cancel each other out. The bent shape ensures that water remains highly polar.

Polarity: The Key to Water’s Uniqueness

The combination of polar covalent bonds and bent geometry makes water a polar molecule. The oxygen end of the molecule carries a partial negative charge (δ-), while the hydrogen ends carry partial positive charges (δ+). This means that a water molecule acts like a tiny magnet, with positive and negative poles.

This polarity is responsible for nearly all of water’s remarkable properties. It allows water molecules to attract each other strongly, creating cohesion. It enables water to dissolve a vast array of substances, earning it the title of “universal solvent.” It explains why water has an unusually high boiling point for such a small molecule, and why ice floats on liquid water, a property that is critical for life on Earth.

Hydrogen Bonding: The Force That Holds It All Together

The polarity of water molecules leads to one of the most important interactions in all of chemistry: hydrogen bonding. When water molecules are near each other, the partially positive hydrogen atom of one molecule is attracted to the partially negative oxygen atom of another molecule. This attraction is called a hydrogen bond.

A hydrogen bond is not as strong as a covalent bond, which holds the atoms within a single water molecule together. A covalent bond in water has an energy of about 460 kilojoules per mole, while a hydrogen bond has an energy of only about 20 kilojoules per mole. Yet hydrogen bonds are strong enough to profoundly affect water’s behavior.

In liquid water, hydrogen bonds are constantly forming and breaking as molecules move around. Each water molecule can form up to four hydrogen bonds: two through its hydrogen atoms (which can each bond to an oxygen on another molecule) and two through its lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen atom (which can each accept a hydrogen bond from another molecule’s hydrogen). This creates a dynamic, three-dimensional network of molecules that are constantly interacting.

When water freezes into ice, the hydrogen bonding becomes more ordered. Water molecules arrange themselves into a crystalline structure that maximizes hydrogen bonding. Remarkably, this structure is less dense than liquid water because the molecules are held in a rigid arrangement that creates more open space. This is why ice floats on water, a nearly unique property among substances and one that has profound implications for life. If ice sank, lakes and oceans would freeze from the bottom up, making it far more difficult for aquatic life to survive cold periods.

Isotopes: Not All Water Molecules Are Identical

While we typically write water’s formula as H₂O, this is actually a simplification. Hydrogen exists in three isotopic forms: protium (¹H), with no neutrons; deuterium (²H or D), with one neutron; and tritium (³H or T), with two neutrons. Oxygen has three stable isotopes: oxygen-16 (¹⁶O), oxygen-17 (¹⁷O), and oxygen-18 (¹⁸O).

The most common form of water is ¹H₂¹⁶O, but nature produces many variations. Water containing deuterium (D₂O) is called heavy water and has slightly different properties from normal water. It’s about 11% denser and has a higher boiling point (101.4°C versus 100°C for regular water). Heavy water occurs naturally, making up about 0.0156% of all water on Earth.

Scientists use the ratios of these isotopes as powerful tools. By measuring the relative amounts of oxygen-18 and oxygen-16 in ice cores, ancient shells, or rocks, researchers can determine temperatures from millions of years ago. Water molecules with lighter isotopes evaporate more easily, so the ratio of isotopes in precipitation varies with temperature and location, creating a fingerprint that reveals where and when water formed.

Water’s Physical Properties: Consequences of Its Structure

The molecular structure of water gives rise to a suite of remarkable physical properties that make it unlike almost any other substance.

High specific heat capacity: Water can absorb or release large amounts of heat with relatively small changes in temperature. This occurs because much of the heat energy goes into breaking hydrogen bonds rather than increasing molecular motion. This property helps regulate Earth’s climate and allows organisms to maintain stable internal temperatures.

High heat of vaporization: It takes a great deal of energy to convert liquid water into vapor because all the hydrogen bonds must be broken. This makes sweating an effective cooling mechanism for organisms and plays a crucial role in Earth’s climate system.

Surface tension: Water has one of the highest surface tensions of any liquid. At the surface, water molecules are pulled inward by hydrogen bonds to other molecules below, creating a kind of elastic “skin.” This allows insects to walk on water and enables water to move up through plants against gravity via capillary action.

Expansion upon freezing: Unlike most substances, water expands when it freezes. As mentioned earlier, this occurs because the hydrogen bonding in ice creates an open crystalline structure. This property means that ice is less dense than liquid water, allowing it to float and insulating the water below from freezing temperatures.

Excellent solvent properties: Water’s polarity allows it to dissolve ionic compounds (like salt) and polar molecules. Water molecules surround ions or polar molecules, separating them from each other in a process called hydration or solvation. This makes water essential for biochemistry, as it allows nutrients, gases, and waste products to be transported in solution.

Part II: The Cosmic Origin of Water’s Components

To understand where water comes from, we must first understand where its constituent atoms, hydrogen and oxygen, originated. This story begins shortly after the Big Bang and continues through billions of years of stellar evolution.

Hydrogen: Born in the First Three Minutes

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and it was the first element to form. In the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang, about 13.8 billion years ago, the universe was unimaginably hot and dense, filled with a seething plasma of fundamental particles: quarks, electrons, photons, and neutrinos.

As the universe expanded and cooled over the first few microseconds, quarks combined to form protons and neutrons. After about three minutes, when the temperature had dropped to around one billion degrees Kelvin, protons and neutrons began to fuse together in a process called Big Bang nucleosynthesis. This process created helium nuclei and trace amounts of lithium and beryllium, but the vast majority of protons remained alone as hydrogen nuclei.

After about 380,000 years, when the universe had cooled to about 3,000 Kelvin, these hydrogen nuclei captured electrons to become neutral hydrogen atoms. This moment, called recombination, was when the universe became transparent to light for the first time. The cosmic microwave background radiation that we detect today is the afterglow of this moment.

Approximately three-quarters of the normal matter in the universe remains hydrogen to this day. Every hydrogen atom in every water molecule on Earth was formed in those first moments after the Big Bang.

Oxygen: Forged in the Hearts of Stars

The story of oxygen is very different. Oxygen, the third most abundant element in the universe (after hydrogen and helium), was not created in the Big Bang. Instead, it was forged billions of years later in the nuclear furnaces of stars.

Stars are powered by nuclear fusion, the process of combining lighter atomic nuclei into heavier ones, releasing tremendous amounts of energy in the process. For most of a star’s life, it fuses hydrogen nuclei (protons) into helium in its core. When a star has converted enough of its core hydrogen into helium, the core contracts and heats up, eventually becoming hot enough to fuse helium into heavier elements.

In stars with masses greater than about eight times the mass of our sun, this process continues through multiple stages. Helium fuses into carbon and oxygen. Carbon fuses into neon and magnesium. The process continues, creating progressively heavier elements in the star’s core, arranged in layers like an onion, with the heaviest elements at the center.

Oxygen is primarily created through a process called helium burning, which occurs at temperatures of about 100 million Kelvin. Three helium nuclei (alpha particles) fuse together to form carbon-12. Then, another helium nucleus fuses with the carbon to form oxygen-16, the most common isotope of oxygen.

But this oxygen doesn’t remain locked in the star’s core. When a massive star reaches the end of its life and has built up an iron core (iron being the endpoint of energy-producing fusion), the core collapses catastrophically, triggering a supernova explosion. This explosion is one of the most energetic events in the universe, briefly outshining an entire galaxy.

The supernova blasts the star’s outer layers, rich in oxygen and other elements created during the star’s life, into space at tremendous velocities. This material, enriched with heavy elements, mixes with the surrounding interstellar medium, the thin gas that exists between stars.

The Interstellar Medium: Where Atoms Meet

The interstellar medium is far from empty. Though its density is extraordinarily low by Earth standards (typically less than one atom per cubic centimeter), it contains vast clouds of gas and dust enriched with the products of stellar nucleosynthesis. These clouds contain hydrogen, helium, and heavier elements like oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and iron.

In the cold, dense regions of these clouds, where temperatures can drop to just 10-20 Kelvin above absolute zero, atoms can come together. However, forming water molecules in the gas phase is challenging because it requires a third body to carry away excess energy from the reaction between hydrogen and oxygen. If this energy isn’t carried away, the newly formed molecule simply breaks apart again.

Instead, water forms primarily on the surfaces of tiny dust grains made of silicates and carbon. These dust grains, typically only about a tenth of a micron across, serve as meeting places for atoms. When hydrogen and oxygen atoms land on a dust grain, they can move across its surface until they encounter each other. The dust grain can absorb the excess energy released when chemical bonds form, allowing stable water molecules to form. Over time, layers of water ice build up on these grains.

Ultraviolet light from nearby stars can break apart water molecules, but in the densest parts of molecular clouds, the dust shields molecules from this destructive radiation. These regions become factories for complex molecules, including not just water but also organic compounds like methanol, formaldehyde, and even amino acids.

Water in the Early Solar System

Our solar system formed about 4.6 billion years ago from a rotating disk of gas and dust called the solar nebula. This nebula was part of a molecular cloud that had been enriched with heavy elements from previous generations of stars.

In the inner solar system, close to the forming Sun, temperatures were too high for water ice to exist. Water could only persist as vapor. Beyond a certain distance from the Sun, called the frost line or snow line (located at about 2.7 astronomical units, or roughly between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter), temperatures were low enough for water vapor to condense into ice. This frost line was critical in determining the composition and characteristics of the planets.

The inner rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars) formed from materials that could survive high temperatures: silicates and metals. They were born relatively dry. The outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) formed beyond the frost line, where they could incorporate vast amounts of water ice along with other frozen volatiles. This is why the giant planets are so much more massive than the rocky planets.

But if Earth formed in a hot, dry region of the solar nebula, where did its water come from? This question has been one of the most intriguing puzzles in planetary science, and answering it requires detective work using isotopic fingerprints.

Part III: How Earth Got Its Water

Earth possesses an extraordinary amount of water. The oceans contain about 1.386 billion cubic kilometers of water, and significant amounts exist in ice caps, groundwater, lakes, rivers, soil moisture, the atmosphere, and even locked within minerals in the Earth’s interior. The total mass of water on Earth is estimated at about 1.4 × 10²¹ kilograms. But Earth formed in a region of the solar system where water should not have been able to condense. So where did all this water come from?

Theory 1: Water Delivered by Asteroids

One leading theory is that much of Earth’s water was delivered by impacts from asteroids and comets after the planet had formed. In the early solar system, the planets were still growing through collisions with smaller bodies called planetesimals. This period of heavy bombardment, which peaked during an event called the Late Heavy Bombardment about 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago, saw countless impacts on the inner planets.

Many of these impactors came from the outer solar system and contained significant amounts of water ice. Asteroids from the outer asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter and near the frost line, are rich in water and organic compounds. A class of asteroids called carbonaceous chondrites can contain up to 20% water by weight, locked within their minerals.

Supporting this theory, scientists have measured the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen (D/H ratio) in various solar system bodies. This ratio serves as a fingerprint that can indicate where water originated. Earth’s ocean water has a D/H ratio of about 156 parts per million. Measurements of carbonaceous chondrite meteorites (which are pieces of asteroids that have fallen to Earth) show D/H ratios very similar to Earth’s oceans.

Computer simulations of the early solar system support the idea that Earth could have been struck by many water-rich asteroids. The gravitational influence of Jupiter could have perturbed the orbits of asteroids, sending them on chaotic paths that intersected with the inner planets. Even though each individual asteroid might have contained relatively little water, the cumulative effect of millions of impacts over hundreds of millions of years could have delivered enough water to fill Earth’s oceans.

Theory 2: Water Delivered by Comets

Comets, often called “dirty snowballs,” are composed largely of water ice mixed with dust and frozen gases. They originate from the cold outer reaches of the solar system, in regions called the Kuiper Belt (beyond Neptune) and the Oort Cloud (a spherical shell extending up to 100,000 astronomical units from the Sun). Occasionally, gravitational perturbations send comets plunging toward the inner solar system.

For many years, comets were considered the most likely source of Earth’s water. They contain abundant water, and impacts from comets during the Late Heavy Bombardment could have delivered substantial amounts to the young Earth.

However, measurements of the D/H ratio in comets have raised doubts about this theory. Several comets that have been measured, including Halley, Hale-Bopp, and Hartley 2, show D/H ratios that are about twice as high as Earth’s ocean water. If comets were the primary source of Earth’s water, we would expect the D/H ratios to match more closely.

That said, not all comets have the same composition. Comet 103P/Hartley 2, which originates from the Kuiper Belt rather than the Oort Cloud, was found to have a D/H ratio matching Earth’s oceans. This suggests that some comets, particularly those from the Kuiper Belt, might have contributed to Earth’s water inventory. The current consensus is that comets probably delivered some of Earth’s water, but they were not the primary source.

Theory 3: Water Present from Earth’s Formation

A more recent theory proposes that Earth might have incorporated water during its initial formation, rather than receiving it all through later impacts. This idea challenges the traditional view that the inner solar system was too hot for water.

Research on meteorites called enstatite chondrites has provided support for this theory. These meteorites are thought to represent the material from which Earth formed because they match Earth’s isotopic composition for oxygen and other elements. Although enstatite chondrites formed at high temperatures and were thought to be dry, recent studies have found that they contain more hydrogen than previously believed, locked within their minerals.

If the building blocks of Earth contained this hydrogen, chemical reactions during the planet’s formation could have produced water. As the planet grew and heated up from gravitational compression and radioactive decay, this water could have been released through volcanic outgassing, gradually accumulating on the surface.

This theory is also supported by the discovery of water deep within Earth’s interior. The minerals in Earth’s mantle can incorporate water into their crystal structures. Some estimates suggest that the mantle might contain as much water as all the surface oceans, or even more. This deep water reservoir could represent water that was present when Earth formed, rather than being delivered from space.

The Most Likely Scenario: A Combination

The truth is probably that Earth’s water came from multiple sources. Some water may have been incorporated during Earth’s initial formation from hydrogen-bearing minerals. Additional water was almost certainly delivered by impacts from asteroids, particularly carbonaceous chondrites from the outer asteroid belt. Comets, especially those from the Kuiper Belt, may have contributed a smaller fraction.

The relative contributions from each source remain a topic of active research. Scientists are using increasingly sophisticated techniques to measure isotopic ratios not just for hydrogen and oxygen, but also for other elements like nitrogen and noble gases, which can provide additional clues about the origins of Earth’s volatiles.

Water on Other Planets: A Comparative Perspective

Understanding Earth’s water also benefits from studying water elsewhere in the solar system.

Mars once had abundant surface water, with evidence of ancient rivers, lakes, and possibly even oceans. Much of this water has been lost to space over billions of years because Mars lacks a strong magnetic field to protect its atmosphere from being stripped away by the solar wind. Some water remains as ice at the poles and in the subsurface.

Venus, despite being Earth’s near-twin in size and location, is bone-dry today. It may have once had oceans, but a runaway greenhouse effect evaporated them. Ultraviolet light broke apart water molecules in the upper atmosphere, and hydrogen escaped to space while oxygen reacted with surface rocks.

Europa, a moon of Jupiter, has more water than Earth. Beneath its icy surface lies a global ocean of liquid water, kept from freezing by tidal heating from Jupiter’s gravity. Several other moons in the outer solar system (Enceladus, Titan, Ganymede, Callisto) also have subsurface oceans.

The Moon, our closest neighbor, was thought to be completely dry until recent discoveries revealed water ice in permanently shadowed craters at the poles, and even molecular water trapped in sunlit lunar soils.

These diverse water inventories across the solar system help scientists understand the complex processes that distributed water after the solar system formed.

Part IV: The Journey of Earth’s Water Through Time

Once water arrived on Earth, its story was far from over. Earth’s water has been on an extraordinary journey through geological and biological systems for billions of years.

The Early Ocean: Hadean and Archean Eons

Earth formed about 4.54 billion years ago, and for its first several hundred million years, it was a hellish world. This period, called the Hadean Eon (after Hades, the Greek underworld), saw Earth bombarded by asteroids and comets. The surface was largely molten, with vast oceans of magma.

As Earth cooled and the bombardment subsided, water vapor released through volcanic outgassing and delivered by impacts began to condense, forming the first oceans. The exact timing is uncertain, but evidence from ancient zircon crystals found in Western Australia suggests that liquid water existed on Earth’s surface at least 4.4 billion years ago, just 150 million years after the planet formed.

These early oceans were very different from today’s. The atmosphere contained virtually no oxygen, the ocean chemistry was different, and the water may have been much warmer due to greater heat flow from Earth’s interior and a dimmer young Sun paradoxically offset by a stronger greenhouse effect.

Yet in these ancient oceans, one of the most profound events in Earth’s history occurred: the emergence of life. The earliest evidence for life dates back at least 3.5 billion years, and possibly as far back as 3.8 billion years. This early life was microscopic and simple, but it would eventually transform the planet and its water.

The Great Oxidation Event: Life Transforms Water

For the first two billion years of life on Earth, organisms were anaerobic, thriving in an oxygen-free environment. But around 2.4 billion years ago, a group of bacteria called cyanobacteria evolved a revolutionary capability: photosynthesis using water as an electron donor.

This process, called oxygenic photosynthesis, splits water molecules to extract electrons, releasing oxygen gas as a waste product. The chemical equation is deceptively simple:

6 CO₂ + 6 H₂O + light energy → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6 O₂

This innovation had profound consequences. Oxygen began accumulating in the atmosphere, eventually reaching levels high enough to form an ozone layer that shields the surface from harmful ultraviolet radiation. The oxidation of iron dissolved in the oceans created the massive banded iron formations that are now important iron ore deposits. Most significantly, the availability of oxygen enabled the evolution of aerobic respiration, a far more efficient way to extract energy from food, which ultimately made complex life possible.

Photosynthesis doesn’t create or destroy water molecules overall, but it does break them apart and incorporate their components into biological molecules. Every plant, every tree, every photosynthetic organism is constantly splitting water molecules, using their hydrogen to build organic compounds while releasing oxygen to the atmosphere.

The Hydrological Cycle: Water in Motion

Today, Earth’s water is in constant motion through the hydrological cycle, also called the water cycle. This global system transports water between the oceans, atmosphere, land, and living organisms.

The cycle begins with evaporation, where solar energy converts liquid water at the surface into water vapor. The oceans account for about 86% of global evaporation. Plants also release water vapor through transpiration, where water absorbed by roots is transported up through the plant and released through tiny pores in leaves. Together, evaporation and transpiration (sometimes called evapotranspiration) transfer about 500,000 cubic kilometers of water to the atmosphere each year.

Water vapor rises into the atmosphere, where it cools and condenses around tiny particles (such as dust or salt) to form clouds. When the water droplets or ice crystals in clouds become large enough, they fall as precipitation: rain, snow, sleet, or hail. About 78% of precipitation falls directly back into the oceans, while 22% falls on land.

Water that falls on land may take several paths. Some evaporates directly back into the atmosphere. Some is absorbed by plants and transpired. Some flows over the surface as runoff, eventually reaching streams and rivers that carry it back to the ocean. Some infiltrates into the ground, becoming groundwater. Groundwater can remain underground for periods ranging from days to millions of years before eventually seeping into streams, springs, or directly into the ocean.

In cold regions, precipitation that falls as snow can accumulate as glaciers and ice sheets, storing water for thousands or even millions of years. During ice ages, so much water is locked up in ice that sea levels drop by over 100 meters. When the ice melts during warm periods, sea levels rise again.

The average residence time of a water molecule in different parts of the cycle varies enormously. In the atmosphere, water vapor remains for about 9 days. In rivers, about 2-3 weeks. In the top layers of the ocean, about 100 years. In glaciers, thousands of years. In deep ocean water, over 1,000 years. In deep groundwater, up to 10,000 years or more.

Water in Living Organisms

Water is not just the environment in which life exists; it is an integral part of life itself. Living organisms are mostly water. The human body is approximately 60% water by weight, though this varies with age and body composition. A jellyfish is 95% water, while even relatively dry organisms like humans contain more water than any other substance.

Water serves countless functions in living things. It is the solvent in which biochemical reactions occur. It transports nutrients and waste products. It helps regulate temperature through evaporative cooling. It provides structural support to cells through turgor pressure. It participates directly in many chemical reactions, including the digestion of food through hydrolysis.

The water in our bodies is not static. We constantly lose water through breathing, sweating, urination, and other processes, and must replenish it by drinking and eating. The water molecules in your body right now will not be the same molecules next month. They are part of the great circulation of water through the biosphere.

Some of the water molecules you drink today were once in the oceans, or in clouds, or in rivers, or in other organisms. They may have been frozen in glaciers, or locked in rocks deep underground, or consumed by dinosaurs 100 million years ago. Each water molecule has traveled through countless forms and locations over Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history.

Water’s Future on Earth

What does the future hold for Earth’s water? On human timescales, the amount of water on Earth remains essentially constant. Water is neither created nor destroyed in significant amounts by geological or biological processes. The same water molecules cycle endlessly through the hydrosphere, atmosphere, lithosphere, and biosphere.

However, on geological timescales, Earth is gradually losing water. High in the atmosphere, ultraviolet radiation from the Sun splits some water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen, being very light, can escape Earth’s gravity and be lost to space. This process is extremely slow—Earth loses only a tiny fraction of its water over millions of years.

Looking billions of years into the future, Earth’s water faces a more dramatic fate. The Sun, like all stars, is gradually brightening as it ages. In about one to two billion years, the Sun will be about 10% brighter than it is today. This increase in solar radiation will heat Earth’s surface, causing increased evaporation and putting more water vapor into the atmosphere.

Water vapor is a powerful greenhouse gas, so this will cause further warming in a runaway greenhouse effect similar to what happened on Venus. Eventually, the oceans will evaporate entirely. The water vapor in the atmosphere will be broken apart by solar radiation, and the hydrogen will escape to space. Earth will become a dry, lifeless world.

But for now, and for millions of years to come, Earth remains a water world, with its precious water cycling through rock, air, ice, ocean, and life in an endless dance that makes our planet unique in the solar system.

Conclusion: Water as a Cosmic and Chemical Marvel

The story of water is simultaneously simple and profound. At the molecular level, water is just two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom. Yet this simple arrangement creates a substance with extraordinary properties that make it essential for life and central to our planet’s climate and geology.

The origin of water’s components spans the history of the universe. The hydrogen in every water molecule was born in the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. The oxygen was forged in the cores of massive stars that lived and died long before our solar system existed. These atoms met in the cold depths of interstellar space, formed water molecules on dust grains in a molecular cloud, and were incorporated into the disk of material that eventually formed our solar system.

Earth’s water likely came from multiple sources: some incorporated during the planet’s formation, more delivered by impacts from asteroids and comets during the solar system’s violent youth. Once here, water has been continuously recycled through rock, ocean, ice, atmosphere, and living organisms for over four billion years.

Understanding water—what it is made of and where it comes from—connects us to the cosmos. Every glass of water we drink contains molecules with an extraordinary history, a history that encompasses the entire universe and the entire span of cosmic time. In a very real sense, we are drinking stardust that has been on an unimaginable journey to reach us.

This knowledge makes water even more precious. As we face challenges of water scarcity, pollution, and climate change in the 21st century, understanding the deep history and fundamental nature of water can inspire us to protect and preserve this remarkable substance that makes life possible on our blue planet.

Be First to Comment