1. Introduction to Materials Science

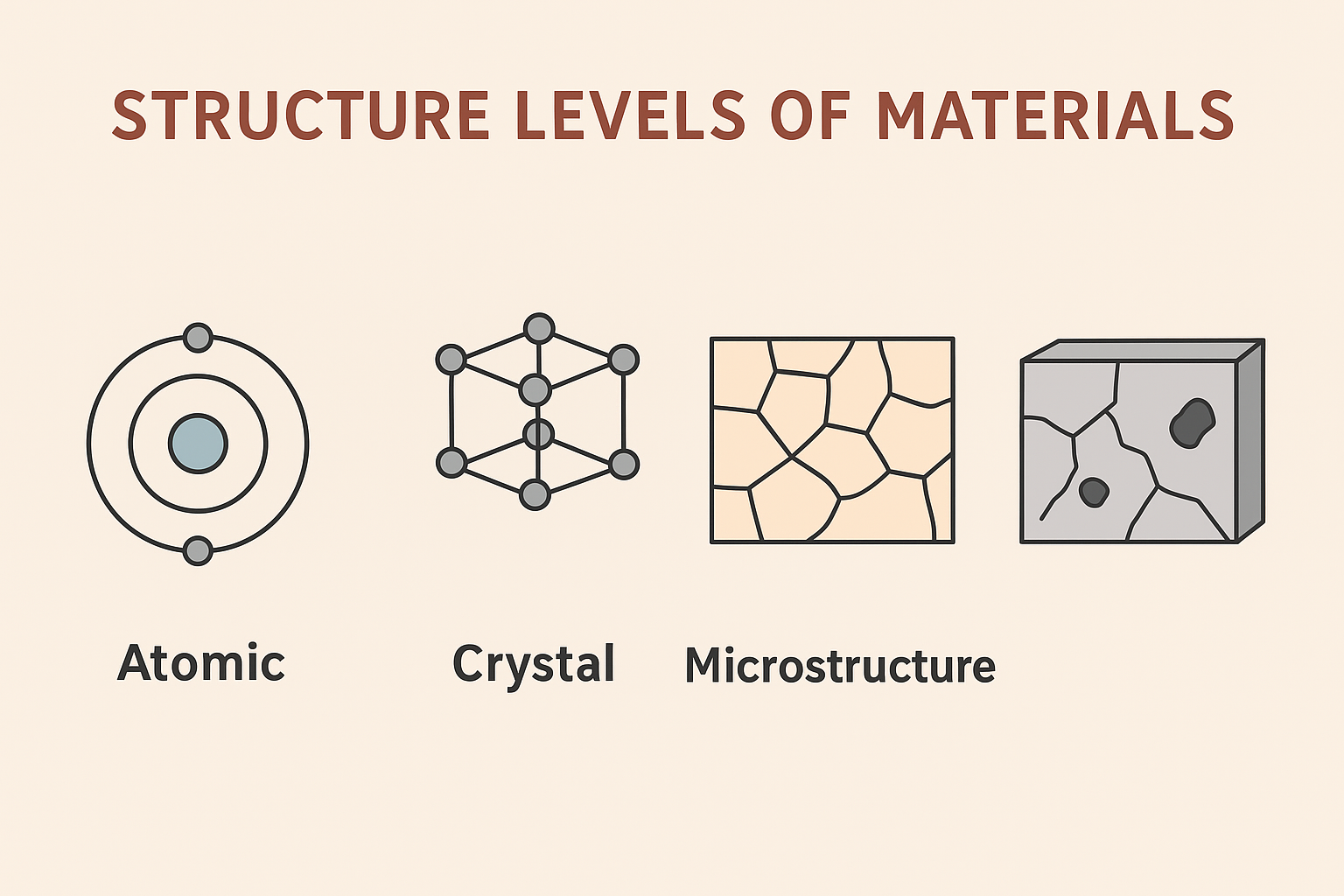

Materials science is an interdisciplinary field that investigates the relationship between the structure, properties, processing, and performance of materials. It combines elements of physics, chemistry, and engineering to understand how materials behave at atomic and molecular levels, and how these behaviors can be manipulated to create new materials with enhanced properties for various applications. This field is crucial for technological advancement, as virtually every innovation, from advanced electronics to biomedical implants, relies on the development and intelligent application of materials.

The study of materials science encompasses a vast array of topics, including the fundamental atomic and molecular structures of solids, the types of bonds that hold atoms together, the crystalline and amorphous arrangements of atoms, and the defects that inevitably exist within these structures. Furthermore, it delves into the various properties that define a material’s utility, such as mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, thermal resistance, and optical characteristics. Understanding these foundational aspects allows scientists and engineers to predict how materials will perform under different conditions and to design new materials tailored to specific needs.

This tutorial aims to provide a detailed overview of the fundamental concepts in materials science technology. We will explore the classification of materials, delve into atomic structure and interatomic bonding, examine crystal structures and their inherent defects, discuss various material properties, and introduce the critical role of phase diagrams and heat treatment in modifying material behavior. By the end of this tutorial, readers will have a solid understanding of the core principles that govern the world of materials and their technological applications.

2. Classification of Materials

Solid materials are broadly categorized into several classes based on their chemical composition, atomic structure, and resulting properties. The primary classifications include metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites. Each class possesses distinct characteristics that make them suitable for different engineering and technological applications.

Metals

Metals are typically characterized by their high electrical and thermal conductivity, lustrous appearance, and malleability. They are generally strong, dense, and ductile, meaning they can be drawn into wires. The unique properties of metals stem from their metallic bonding, where valence electrons are delocalized and shared among a lattice of positively charged ions. This ‘sea’ of electrons allows for efficient conduction of heat and electricity and contributes to their ability to deform plastically without fracturing. Common examples of metals include iron, copper, aluminum, and their alloys like steel and brass.

Ceramics

Ceramics are inorganic, non-metallic solids that are typically formed by heating and cooling. They are known for their high hardness, strength, and high melting points, making them suitable for high-temperature applications. Unlike metals, ceramics are generally poor conductors of electricity and heat, and they tend to be brittle. Their bonding is predominantly ionic or covalent, which results in strong, rigid structures but limits their ability to deform plastically. Examples include glass, porcelain, alumina, and silicon carbide.

Polymers

Polymers are large molecules, or macromolecules, composed of many repeated subunits called monomers. These materials are typically lightweight, flexible, and possess a wide range of properties depending on their molecular structure and composition. Polymers are generally electrical and thermal insulators. Their properties are largely influenced by covalent bonds within the polymer chains and weaker secondary bonds (like Van der Waals forces or hydrogen bonds) between chains. Common examples include plastics (e.g., polyethylene, polypropylene), rubber, and nylon.

Composites

Composite materials are engineered materials made from two or more constituent materials with significantly different physical or chemical properties. When combined, these materials produce a new material with characteristics superior to those of the individual components. Composites typically consist of a matrix material (which binds the reinforcement) and a reinforcement material (which provides strength and stiffness). The goal of creating composites is to achieve a synergistic effect, optimizing properties such as strength-to-weight ratio, stiffness, and durability. Examples include fiberglass (glass fibers in a polymer matrix), carbon fiber reinforced polymers, and reinforced concrete.

3. Atomic Structure and Interatomic Bonding

All matter is composed of atoms, and the way these atoms are arranged and bonded together fundamentally dictates the properties of a material. Understanding atomic structure and interatomic bonding is therefore a cornerstone of materials science.

Basic Atomic Structure

An atom consists of a nucleus, containing protons and neutrons, surrounded by electrons orbiting in distinct energy levels or shells. The number of protons defines the element, while the arrangement of electrons, particularly those in the outermost shell (valence electrons), determines an atom’s chemical reactivity and its ability to form bonds with other atoms. Atoms tend to achieve a stable electron configuration, typically a full outer shell, by interacting with other atoms.

Primary Bonds

Primary bonds are strong chemical bonds that involve significant changes in the electron configurations of the interacting atoms. These bonds are responsible for the structural integrity and many fundamental properties of materials.

Ionic Bonding

Ionic bonding occurs when there is a complete transfer of one or more valence electrons from one atom to another. This typically happens between a metallic atom (which tends to lose electrons) and a non-metallic atom (which tends to gain electrons). The atom that loses electrons becomes a positively charged ion (cation), and the atom that gains electrons becomes a negatively charged ion (anion). The electrostatic attraction between these oppositely charged ions forms the ionic bond. Materials with ionic bonds, such as ceramics (e.g., NaCl, Al2O3), are typically hard, brittle, and have high melting points, and are generally poor electrical conductors in their solid state due to the immobility of their electrons.

Covalent Bonding

Covalent bonding involves the sharing of valence electrons between two atoms. This type of bonding typically occurs between non-metallic atoms. Each shared pair of electrons constitutes a single covalent bond. Covalent bonds are strong and highly directional, meaning the atoms are arranged in specific geometric configurations. Materials with predominant covalent bonding, such as diamond, silicon, and many polymers, are often very hard, have high melting points, and can be electrical insulators or semiconductors, depending on the specific electron configuration and band structure.

Metallic Bonding

Metallic bonding is characteristic of metals and their alloys. In this type of bond, the valence electrons are not localized to individual atoms or bonds but are delocalized and shared among a vast lattice of positively charged metal ions. This arrangement is often described as a

‘sea of delocalized electrons.’ This electron mobility is responsible for the characteristic properties of metals, including high electrical and thermal conductivity, ductility (ability to be drawn into wires), and malleability (ability to be hammered into sheets). Examples include copper, iron, and aluminum.

Secondary Bonds (Van der Waals Bonds)

Secondary bonds, also known as Van der Waals bonds, are much weaker than primary bonds and arise from temporary or permanent electrostatic attractions between molecules or atomic dipoles. While individually weak, these forces can be significant when numerous bonds are present, influencing properties like melting points and mechanical strength in materials where primary bonds are absent or less dominant.

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a special type of dipole-dipole interaction that occurs when a hydrogen atom, covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom (such as oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine), is attracted to another electronegative atom in a different molecule or within the same molecule. These bonds are stronger than other Van der Waals forces and play a crucial role in the properties of water, polymers, and biological molecules.

Van der Waals Forces

These are weak attractive forces between atoms or molecules that result from temporary fluctuations in electron distribution, creating instantaneous dipoles. These forces are present in all materials but are most significant in non-polar molecules or in materials where primary bonding is weak or absent. They influence properties such as the boiling points of liquids and the mechanical properties of polymers.

Influence of Bonding on Material Properties

The type and strength of interatomic bonds profoundly influence a material’s properties:

•Mechanical Strength: Materials with strong primary bonds (ionic, covalent, metallic) generally exhibit higher mechanical strength, hardness, and stiffness. For instance, the strong covalent bonds in diamond make it exceptionally hard, while the metallic bonds in steel contribute to its high tensile strength.

•Melting Point: The energy required to break interatomic bonds determines a material’s melting point. Stronger bonds necessitate more energy, leading to higher melting temperatures. This is why ceramics (ionic/covalent) and metals typically have much higher melting points than polymers (covalent within chains, weak secondary between chains).

•Electrical Conductivity: The presence of free or delocalized electrons is essential for high electrical conductivity. Metallic bonds, with their electron sea, facilitate excellent conductivity. Ionic and covalently bonded materials, where electrons are localized, are generally insulators or semiconductors.

•Ductility and Malleability: These properties, characteristic of metals, are a direct consequence of metallic bonding. The non-directional nature of metallic bonds allows atomic planes to slide past each other without breaking the overall bond, enabling plastic deformation.

•Brittleness: Materials with strong, directional bonds (like many ceramics) tend to be brittle. When stress is applied, these bonds resist deformation and instead fracture along specific planes, as breaking the directional bonds requires significant energy and leads to catastrophic failure rather than plastic flow.

4. Crystal Structure and Defects

Many engineering materials are crystalline, meaning their atoms are arranged in a highly ordered, repeating pattern extending in all three dimensions. This ordered arrangement, known as the crystal structure, significantly influences a material’s properties. However, real crystals are never perfect and contain various types of imperfections, or defects, which also play a crucial role in determining material behavior.

Crystal Structure Fundamentals

Unit Cell

The fundamental building block of a crystal structure is the unit cell. It is the smallest repeating unit that possesses the full symmetry of the entire crystal lattice. Imagine a 3D puzzle; the unit cell is the single piece that, when repeated in all directions, constructs the entire puzzle. The geometry of a unit cell is defined by six lattice parameters: the lengths of its edges (a, b, c) and the angles between them (α, β, γ). The arrangement of atoms within this unit cell, and its overall symmetry, are critical in dictating properties such as cleavage, electronic band structure, and optical transparency.

Miller Indices

To describe specific planes and directions within a crystal lattice, Miller indices are used. This three-value notation (hkl) represents crystallographic planes, while bracketed notation like [hkl] denotes crystallographic directions. Miller indices are derived from the reciprocals of the intercepts a plane makes with the crystallographic axes, normalized to the smallest integers. For example, a (100) plane intercepts the a-axis and is parallel to the b and c axes. These indices are essential for understanding phenomena like slip systems in metals and the orientation-dependent properties of single crystals.

Crystallographic Planes and Directions

Crystallographic directions are imaginary lines connecting atoms within the crystal, and crystallographic planes are imaginary surfaces that pass through atoms. Some directions and planes are more densely packed with atoms than others. These high-density planes and directions are particularly important because they influence:

•Optical Properties: The refractive index, for instance, is directly related to the density of atoms in certain planes.

•Adsorption and Reactivity: Chemical reactions and physical adsorption often occur at surface atoms, making these phenomena sensitive to the atomic density of surface planes.

•Plastic Deformation: In metals, plastic deformation primarily occurs through the movement of dislocations along densely packed planes and in densely packed directions, known as slip systems.

Classification by Symmetry (Crystal Systems)

Crystals are classified into seven crystal systems based on the symmetry of their unit cells. These systems are cubic, tetragonal, hexagonal, rhombohedral (trigonal), orthorhombic, monoclinic, and triclinic. Each system has specific relationships between its lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ) and a unique set of symmetry elements (e.g., rotation axes, mirror planes). For example, the cubic system, characterized by a=b=c and α=β=γ=90°, includes common structures like Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) and Body-Centered Cubic (BCC), which are prevalent in many metals.

Crystallographic Defects

While ideal crystal structures are theoretical constructs, real materials always contain imperfections. These crystallographic defects are deviations from the perfect atomic arrangement and profoundly influence a material’s mechanical, electrical, optical, and chemical properties. Defects are often intentionally introduced or controlled during processing to tailor material performance.

Point Defects

Point defects are localized disruptions in the crystal lattice, occurring at or around a single lattice point. Common types include:

•Vacancies: Missing atoms from a normal lattice site. Vacancies are crucial for atomic diffusion in solids, which is fundamental to many material processes like heat treatment.

•Interstitial Atoms: Extra atoms positioned in sites that are not normally occupied in the crystal structure. These can be either host atoms (self-interstitials) or impurity atoms.

•Substitutional Impurities: Foreign atoms that replace host atoms on regular lattice sites. The size difference between the impurity and host atoms can induce local strains in the lattice, affecting properties.

Line Defects (Dislocations)

Line defects, or dislocations, are one-dimensional defects that cause a localized distortion of the crystal lattice along a line. They are particularly important in metals, as they are the primary mechanism for plastic deformation. The two main types are:

•Edge Dislocation: An extra half-plane of atoms inserted into the crystal lattice. The edge of this extra plane forms the dislocation line.

•Screw Dislocation: A defect that can be visualized as a helical ramp in the crystal lattice, resulting from a shear distortion. The dislocation line is parallel to the shear stress.

The movement of dislocations (slip) allows metals to deform plastically without fracturing, a property known as ductility. Impeding dislocation motion is a key strategy for strengthening metals.

Planar Defects (Grain Boundaries)

Planar defects are two-dimensional imperfections that separate regions of the crystal with different orientations or structures. The most common planar defects are grain boundaries, which are interfaces between adjacent crystallites (grains) in a polycrystalline material. Atoms at grain boundaries are not perfectly aligned, leading to a region of higher energy. Grain boundaries can significantly influence mechanical properties; for example, they can strengthen a material by hindering dislocation movement (Hall-Petch effect) but can also be preferential sites for corrosion or fracture.

Bulk Defects

Bulk defects are three-dimensional imperfections within the material, such as pores, cracks, and inclusions (small particles of a different phase). These defects can act as stress concentrators, significantly reducing a material’s strength and toughness.

Influence of Defects on Material Properties

Defects, far from being mere imperfections, are often critical in tailoring material properties:

•Mechanical Properties: Dislocations are essential for ductility in metals. Controlling their movement (e.g., through alloying or cold working) is how materials are strengthened. Grain boundaries can also strengthen materials. Conversely, cracks and pores can drastically reduce strength and toughness.

•Electrical Properties: Impurities and defects can scatter electrons, reducing electrical conductivity in metals or creating donor/acceptor states in semiconductors, which is fundamental to semiconductor device operation.

•Optical Properties: Defects can absorb or scatter light, affecting a material’s transparency, color, or luminescence.

•Diffusion: Vacancies are crucial for atomic diffusion, enabling processes like heat treatment and phase transformations.

5. Material Properties

Material properties are the characteristics that define how a material responds to external stimuli and environmental conditions. These properties are critical for selecting the right material for a specific application and for designing new materials with desired performance. They can be broadly categorized into mechanical, electrical, thermal, optical, and chemical properties.

Mechanical Properties

Mechanical properties describe how a material reacts to applied forces. These are often the most critical properties for structural and load-bearing applications.

•Strength: This refers to a material’s ability to withstand an applied load without failure. Different types of strength include:

•Tensile Strength: The maximum stress a material can withstand before fracturing when stretched or pulled.

•Compressive Strength: The maximum stress a material can withstand before compressive failure when squeezed.

•Yield Strength: The stress at which a material begins to deform plastically (permanently).

•Ductility and Malleability:

•Ductility: A material’s ability to deform under tensile stress without fracturing, allowing it to be drawn into wires. Examples include copper and aluminum.

•Malleability: A material’s ability to deform under compressive stress without fracturing, allowing it to be hammered or rolled into thin sheets. Gold is highly malleable.

•Hardness: The resistance of a material to localized plastic deformation, such as indentation or scratching. Hardness is often measured using tests like Brinell, Rockwell, or Vickers.

•Toughness and Brittleness:

•Toughness: A material’s ability to absorb energy and deform plastically before fracturing. Tough materials resist crack propagation.

•Brittleness: The tendency of a material to fracture with little or no plastic deformation. Brittle materials, like ceramics, often fail suddenly.

•Elasticity and Plasticity:

•Elasticity: The ability of a material to return to its original shape after the removal of an applied load. This is a temporary, recoverable deformation.

•Plasticity: The ability of a material to undergo permanent deformation without fracturing after the applied load is removed.

•Creep and Fatigue:

•Creep: The time-dependent, permanent deformation of a material under a constant load at elevated temperatures. It is a critical consideration for components operating in high-temperature environments.

•Fatigue: The weakening of a material caused by repeatedly applied loads, leading to fracture at stresses well below the material’s static tensile strength. Fatigue failure is common in components subjected to cyclic loading.

Electrical Properties

Electrical properties describe a material’s response to an electric field.

•Conductivity and Resistivity:

•Electrical Conductivity: A measure of a material’s ability to conduct electric current. Metals are excellent conductors due to their free electrons.

•Electrical Resistivity: The inverse of conductivity, representing a material’s opposition to the flow of electric current. Insulators have high resistivity.

•Dielectric Properties: Relate to a material’s ability to store electrical energy in an electric field. Dielectric materials are used as insulators in capacitors.

Thermal Properties

Thermal properties describe how a material responds to changes in temperature or heat flow.

•Thermal Conductivity: A material’s ability to transfer heat. Materials with high thermal conductivity (e.g., metals) are good heat sinks, while those with low thermal conductivity (e.g., ceramics, polymers) are good insulators.

•Thermal Expansion: The tendency of matter to change in volume in response to a change in temperature. The coefficient of thermal expansion quantifies this change.

•Heat Capacity: The amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of a given mass of a material by a certain amount.

Optical Properties

Optical properties describe a material’s interaction with light.

•Absorption, Reflection, and Transmission: How a material absorbs, reflects, or transmits light. These properties determine a material’s color and transparency.

•Refractive Index: A measure of how much light is bent, or refracted, when it passes from one medium to another. It is crucial for optical lenses and fibers.

Chemical Properties

Chemical properties describe a material’s behavior in chemical reactions and its stability in various environments.

•Corrosion Resistance: A material’s ability to resist degradation due to chemical or electrochemical reactions with its environment. This is particularly important for metals exposed to harsh conditions.

•Reactivity: How readily a material undergoes chemical reactions with other substances. Some materials are highly reactive (e.g., alkali metals), while others are inert (e.g., noble gases).

6. Phase Diagrams and Transformations

Phase diagrams are indispensable tools in materials science and engineering, serving as graphical maps that illustrate the conditions under which different phases of a material or alloy coexist at equilibrium. They are crucial for understanding how materials behave under varying conditions of temperature, pressure, and composition, and for designing processing routes to achieve desired microstructures and properties.

Introduction to Phase Diagrams

A phase is a homogeneous portion of a material system that has uniform physical and chemical characteristics. For example, ice, liquid water, and water vapor are three distinct phases of H2O. Phase diagrams typically plot temperature on one axis and composition (for multi-component systems) or pressure (for single-component systems) on the other. The lines on these diagrams, known as phase boundaries, delineate regions where different phases or combinations of phases are stable.

Types of Phase Diagrams

•Unary Phase Diagrams: These are the simplest type, representing a single-component system (e.g., pure water or pure iron). They typically show the stable phases as a function of temperature and pressure. Key features include triple points (where three phases coexist) and critical points (where liquid and gas phases become indistinguishable).

•Binary Phase Diagrams: These diagrams illustrate the phase relationships in a two-component system as a function of temperature and composition (usually at constant pressure). They are fundamental for understanding alloys and mixtures. The most widely studied example is the Iron-Carbon (Fe-C) phase diagram, which is critical for understanding steels and cast irons.

•Ternary Phase Diagrams: These represent three-component systems and are typically depicted using triangular plots, where each corner corresponds to a pure component. They are more complex but provide comprehensive insights into multi-component systems, often used in ceramics and advanced alloys.

Key Features of Phase Diagrams

Several important features are common to many phase diagrams:

•Phase Boundaries: Lines separating regions of different stable phases. Along these lines, two phases are in equilibrium.

•Liquidus Line: The line on a phase diagram above which a material is entirely liquid.

•Solidus Line: The line on a phase diagram below which a material is entirely solid.

•Eutectic Point: A specific composition and temperature at which a liquid phase transforms directly into two or more solid phases upon cooling. This point represents the lowest melting temperature for a given alloy system.

•Peritectic Point: A point where a liquid phase and one solid phase react isothermally to form a second, different solid phase upon cooling.

•Solvus Line: A line indicating the limit of solubility of one component in another in the solid state. Crossing this line can lead to precipitation of a new solid phase.

Iron-Carbon Phase Diagram (Detailed Example)

The Iron-Carbon (Fe-C) phase diagram is arguably the most important phase diagram in metallurgy, as it underpins the understanding of steels and cast irons. It typically covers carbon concentrations up to 6.67 wt% (the composition of cementite, Fe3C). Key phases and microconstituents in this diagram include:

•Ferrite (α-Fe): A body-centered cubic (BCC) solid solution of carbon in iron, stable at low temperatures. It is relatively soft and ductile.

•Austenite (γ-Fe): A face-centered cubic (FCC) solid solution of carbon in iron, stable at higher temperatures. It can dissolve significantly more carbon than ferrite and is non-magnetic.

•Cementite (Fe3C): An intermetallic compound of iron and carbon, which is very hard and brittle.

•Pearlite: A lamellar (layered) microstructure consisting of alternating layers of ferrite and cementite, formed by the eutectoid decomposition of austenite upon slow cooling.

•Martensite: A very hard and brittle phase formed by rapid quenching of austenite, preventing carbon diffusion and resulting in a body-centered tetragonal (BCT) structure.

Understanding the Fe-C diagram allows engineers to predict the microstructures that will form upon cooling from various temperatures and compositions, which in turn dictates the mechanical properties of iron-carbon alloys. This knowledge is essential for heat treatment processes.

Phase Transformations

Phase transformations involve changes in the microstructure of a material, often leading to significant alterations in its properties. These transformations can be driven by changes in temperature, pressure, or composition. Two fundamental mechanisms govern these transformations:

Diffusion

Diffusion is the process by which atoms migrate through a material. It is a thermally activated process, meaning it occurs more rapidly at higher temperatures. Diffusion is essential for many phase transformations, as it allows atoms to rearrange themselves to form new phases. For example, the formation of pearlite from austenite involves the diffusion of carbon atoms to form separate ferrite and cementite phases.

Nucleation and Growth

Phase transformations typically proceed via nucleation and growth.

•Nucleation: The initial formation of tiny stable particles (nuclei) of the new phase within the parent phase. This process requires overcoming an energy barrier and can be homogeneous (occurring randomly throughout the parent phase) or heterogeneous (occurring preferentially at defects or grain boundaries).

•Growth: Once stable nuclei are formed, they increase in size as atoms from the parent phase attach to their surfaces. The rate of growth is influenced by temperature and the diffusion rate of atoms.

The interplay between nucleation and growth rates determines the final microstructure and, consequently, the properties of the transformed material. For instance, rapid cooling can suppress diffusion, leading to fine microstructures or even non-equilibrium phases like martensite, which are critical for achieving high strength in steels.

7. Heat Treatment

Heat treatment refers to a group of industrial thermal and sometimes thermochemical processes used to alter the physical, and sometimes chemical, properties of a material. The primary goal of heat treatment is to change the microstructure of a material, thereby enhancing its mechanical properties such as hardness, strength, ductility, and toughness, or improving its electrical and magnetic characteristics. These processes involve heating the material to a specific temperature, holding it there for a certain period, and then cooling it at a controlled rate.

Purpose of Heat Treatment

The main purposes of heat treatment include:

•Increasing Hardness and Strength: By forming harder microstructures (e.g., martensite in steel).

•Improving Ductility and Toughness: By relieving internal stresses and refining grain structures.

•Enhancing Machinability: By making the material softer and easier to cut.

•Improving Wear Resistance: By creating a harder surface.

•Relieving Internal Stresses: Stresses introduced during manufacturing processes like cold working or welding can be detrimental and are often relieved through heat treatment.

•Refining Grain Size: Smaller grains generally lead to improved strength and toughness.

Common Heat Treatment Processes

Several common heat treatment processes are employed, each designed to achieve specific changes in material properties:

Annealing

Annealing involves heating a material to a suitable temperature, holding it there, and then slowly cooling it, usually in the furnace. The primary objectives of annealing are to:

•Relieve internal stresses: Caused by cold working or non-uniform cooling.

•Increase ductility and toughness: By making the material softer.

•Refine grain structure: Leading to improved mechanical properties.

•Improve machinability and cold working properties: By reducing hardness.

Annealing typically results in a softer, more ductile material with a more uniform microstructure.

Normalizing

Normalizing involves heating a material (typically steel) to a temperature above its critical temperature, holding it to allow for complete phase transformation to austenite, and then cooling it in still air. The cooling rate in normalizing is faster than in annealing but slower than in hardening. The main goals are to:

•Refine grain size: Leading to a more uniform and finer grain structure than annealing.

•Improve strength and hardness: Compared to annealed material.

•Reduce internal stresses: Though less effectively than full annealing.

Normalized steels generally have better strength and hardness than annealed steels, making them suitable for applications requiring good mechanical properties without excessive hardness.

Hardening (Quenching)

Hardening is a heat treatment process primarily used to increase the hardness and strength of steel. It involves heating the steel to an austenitic temperature and then rapidly cooling it (quenching) in a medium such as water, oil, or polymer solutions. This rapid cooling prevents the diffusion of carbon atoms, trapping them in a supersaturated solid solution, which transforms austenite into a very hard and brittle phase called martensite. The effectiveness of hardening depends on the carbon content of the steel and the cooling rate.

Tempering

Tempering is almost always performed after hardening to reduce the brittleness of martensite and improve its toughness, while still retaining a significant portion of the hardness. It involves reheating the hardened steel to a temperature below the critical temperature (usually between 150°C and 650°C), holding it for a period, and then cooling it slowly. Tempering causes the decomposition of martensite into a more stable and ductile microstructure, typically consisting of fine carbides dispersed in a ferrite matrix. The specific temperature and time of tempering determine the final balance of hardness and toughness.

Age Hardening (Precipitation Hardening)

Age hardening, or precipitation hardening, is a heat treatment technique used to increase the yield strength of malleable materials, including certain aluminum, magnesium, nickel, and titanium alloys. It involves a multi-step process:

1.Solution Treatment: The alloy is heated to a temperature where the alloying elements dissolve completely into the primary solid solution.

2.Quenching: Rapid cooling to room temperature to retain the alloying elements in a supersaturated solid solution.

3.Aging: The supersaturated solid solution is then heated to an intermediate temperature (artificial aging) or left at room temperature (natural aging) for a period. During aging, fine precipitates of a second phase form within the matrix, which impede dislocation movement and thus strengthen the material.

Age hardening is highly effective in producing high-strength alloys without significantly sacrificing ductility.

Influence of Heat Treatment on Microstructure and Properties

Heat treatment processes exert profound control over the microstructure of materials, which in turn dictates their macroscopic properties. By manipulating temperature and cooling rates, engineers can control:

•Grain Size: Heat treatments can refine or coarsen grain structures, impacting strength and toughness.

•Phase Composition: Different phases (e.g., ferrite, austenite, martensite in steel) have distinct properties, and heat treatment allows for their formation and transformation.

•Distribution of Alloying Elements: Diffusion during heating and cooling can redistribute alloying elements, forming precipitates or solid solutions that enhance properties.

•Internal Stresses: Heat treatment can relieve or introduce internal stresses, affecting dimensional stability and resistance to cracking.

Ultimately, the ability to precisely control these microstructural features through heat treatment is a cornerstone of materials engineering, enabling the production of materials tailored for diverse and demanding applications.

8. Advanced Materials (Brief Overview)

The field of materials science is continuously evolving, with ongoing research and development leading to the creation of advanced materials that push the boundaries of performance and functionality. These materials often exhibit unique properties not found in conventional materials, enabling groundbreaking applications in various industries.

Smart Materials

Smart materials, also known as intelligent or responsive materials, are designed to sense and react to environmental stimuli in a controlled and often reversible manner. These stimuli can include changes in temperature, pressure, electric or magnetic fields, light, or chemical agents. Examples of smart materials include:

•Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs): These alloys can recover their original shape after being deformed when subjected to a specific temperature. Nitinol (Nickel-Titanium alloy) is a common SMA used in medical devices and aerospace applications.

•Piezoelectric Materials: These materials generate an electric charge when subjected to mechanical stress (direct piezoelectric effect) and, conversely, undergo mechanical deformation when an electric field is applied (converse piezoelectric effect). They are used in sensors, actuators, and energy harvesting devices.

•Thermoelectric Materials: These materials can convert temperature differences directly into electrical voltage and vice versa. They are used in refrigeration and power generation.

•Chromogenic Materials: These materials change color in response to external stimuli, such as thermochromic materials (temperature-sensitive) and photochromic materials (light-sensitive). They find applications in smart windows and sensors.

Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials are materials with at least one dimension in the nanoscale (typically 1 to 100 nanometers). At this scale, materials often exhibit novel physical, chemical, and biological properties that differ significantly from their bulk counterparts. This is due to increased surface area-to-volume ratio and quantum mechanical effects. Key types of nanomaterials include:

•Nanoparticles: Ultrafine particles with dimensions in the nanoscale, used in catalysis, medicine (drug delivery), and electronics.

•Nanotubes: Cylindrical nanostructures, such as carbon nanotubes, known for their exceptional strength, electrical conductivity, and thermal properties.

•Nanofilms and Coatings: Thin layers of nanoscale materials applied to surfaces to impart specific properties like corrosion resistance, anti-reflective properties, or enhanced hardness.

•Quantum Dots: Semiconductor nanocrystals that emit light at specific wavelengths depending on their size, used in displays, solar cells, and bioimaging.

Nanomaterials are revolutionizing fields such as electronics, medicine, energy, and environmental science.

Biomaterials

Biomaterials are materials designed to interact with biological systems for medical purposes. They can be natural or synthetic and are used in a wide range of applications, including implants, prosthetics, drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering. The key requirements for biomaterials are biocompatibility (not causing adverse reactions in the body) and the ability to perform their intended function within the biological environment. Examples include:

•Metals: Stainless steel, titanium alloys, and cobalt-chromium alloys are used for orthopedic implants (e.g., hip and knee replacements) due to their strength and corrosion resistance.

•Ceramics: Alumina, zirconia, and calcium phosphates are used for dental implants, bone grafts, and coatings due to their biocompatibility and hardness.

•Polymers: Polyethylene, silicone, and biodegradable polymers (e.g., polylactic acid) are used for sutures, drug delivery, and tissue scaffolds due to their flexibility and tunable degradation rates.

•Composites: Bone cement (PMMA-based) and carbon fiber composites are used where a combination of strength and biocompatibility is required.

The development of advanced materials is a dynamic area of research, continually pushing the boundaries of what is possible and enabling solutions to complex challenges across various sectors.

9. Conclusion

Materials science technology is a vast and dynamic field that underpins nearly every aspect of modern engineering and technological advancement. From the fundamental atomic arrangements and interatomic bonds that dictate a material’s intrinsic characteristics to the complex interplay of microstructure, processing, and properties, a deep understanding of materials is essential for innovation.

This tutorial has explored the foundational concepts of materials science, beginning with the basic classification of materials into metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites, each with its unique set of properties and applications. We delved into the atomic structure and the various types of interatomic bonding—ionic, covalent, and metallic—highlighting how these bonds profoundly influence a material’s mechanical, electrical, and thermal behavior. The discussion then moved to crystal structures, emphasizing the importance of the unit cell, Miller indices, and crystallographic defects, which, far from being mere imperfections, are often critical in tailoring material performance.

Furthermore, we examined the diverse range of material properties, including mechanical (strength, ductility, hardness, toughness), electrical (conductivity, resistivity), thermal (conductivity, expansion), optical (absorption, reflection), and chemical (corrosion resistance, reactivity) characteristics. The role of phase diagrams as invaluable tools for predicting material behavior under varying conditions and the significance of phase transformations were also discussed, with a detailed look at the iron-carbon phase diagram. Finally, we explored heat treatment processes—annealing, normalizing, hardening, tempering, and age hardening—as powerful methods to manipulate microstructure and optimize material properties for specific applications. A brief overview of advanced materials like smart materials, nanomaterials, and biomaterials showcased the cutting edge of materials research.

Future Directions in Materials Science

The field of materials science continues to evolve rapidly, driven by the demand for materials with unprecedented performance, sustainability, and functionality. Future directions include:

•Sustainable Materials: Development of eco-friendly materials, including biodegradable polymers, recycled materials, and materials produced with reduced energy consumption and waste.

•Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): Innovations in materials for 3D printing, enabling the creation of complex geometries and customized components with tailored properties.

•Computational Materials Science: Advanced simulations and machine learning to predict material properties and design new materials virtually, accelerating the discovery process.

•Bio-inspired Materials: Designing materials that mimic the structures and functions of biological systems, leading to self-healing materials, adaptive structures, and advanced prosthetics.

•Energy Materials: Development of materials for efficient energy generation (solar cells, thermoelectric devices), storage (batteries, supercapacitors), and conversion.

By continually pushing the boundaries of materials discovery and engineering, materials scientists and engineers will continue to play a pivotal role in addressing global challenges and driving technological progress for a sustainable future.

Be First to Comment