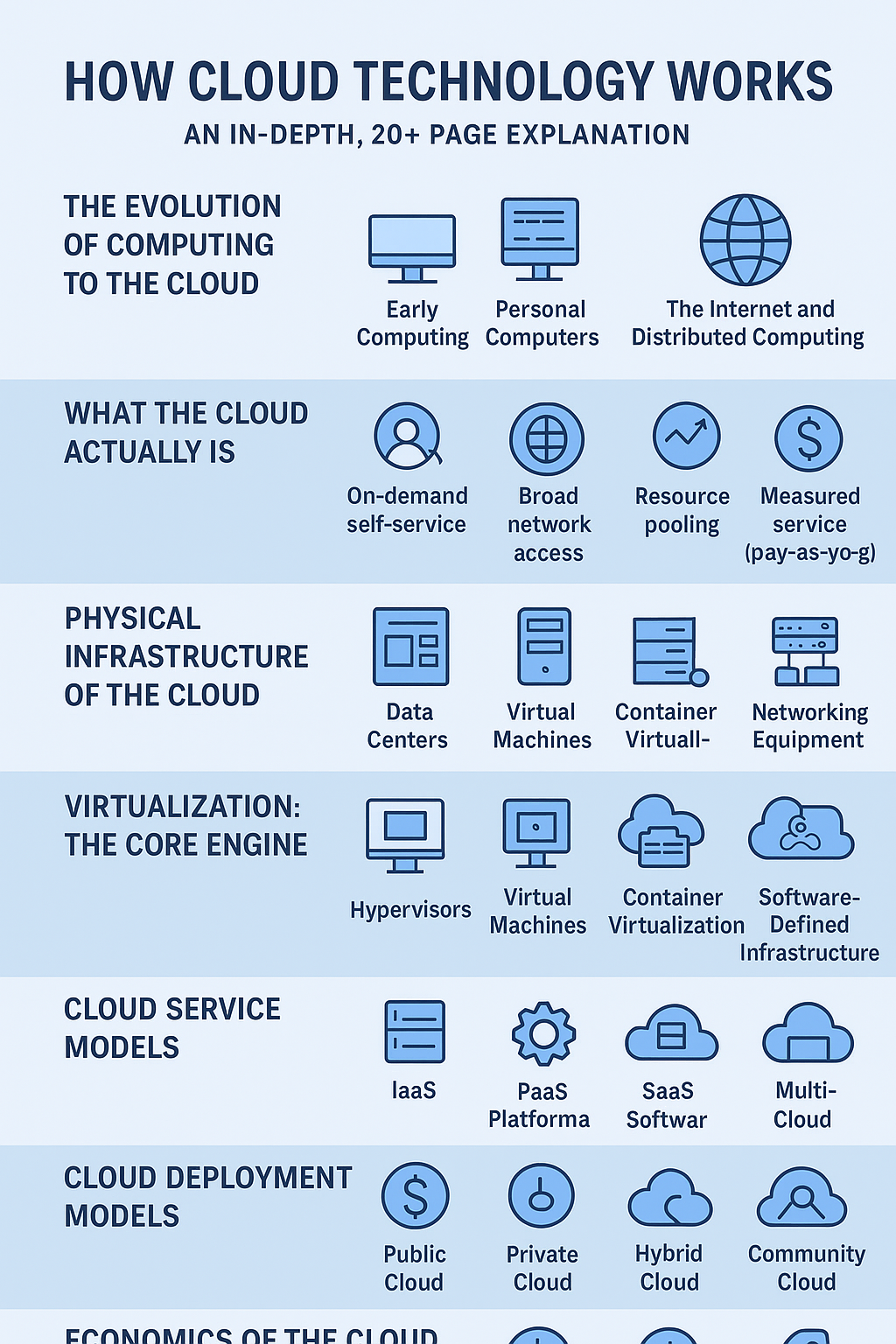

Part I: The Foundation of Cloud Computing

Chapter 1: Defining the Cloud and Its Evolution

1.1 What is Cloud Computing?

Cloud computing represents a paradigm shift in how computing resources are delivered and consumed. At its core, it is the on-demand delivery of IT resources—including applications, storage, processing power, and networking—over the internet with pay-as-you-go pricing. This model fundamentally transforms capital expenditure (CapEx) into operational expenditure (OpEx), allowing businesses to scale rapidly without the burden of managing physical infrastructure.

The definitive understanding of cloud computing is often anchored in the definition provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which identifies five essential characteristics [1]:

- On-demand self-service: A consumer can unilaterally provision computing capabilities, such as server time and network storage, as needed automatically without requiring human interaction with each service provider.

- Broad network access: Capabilities are available over the network and accessed through standard mechanisms that promote use by heterogeneous thin or thick client platforms (e.g., mobile phones, laptops, and PDAs).

- Resource pooling: The provider’s computing resources are pooled to serve multiple consumers using a multi-tenant model, with different physical and virtual resources dynamically assigned and reassigned according to consumer demand. This sense of location independence is a key feature.

- Rapid elasticity: Capabilities can be elastically provisioned and released, in some cases automatically, to scale rapidly outward and inward commensurate with demand. To the consumer, the capabilities available for provisioning often appear to be unlimited and can be appropriated in any quantity at any time.

- Measured service: Cloud systems automatically control and optimize resource use by leveraging a metering capability at some level of abstraction appropriate to the type of service (e.g., storage, processing, bandwidth, and active user accounts). Resource usage can be monitored, controlled, and reported, providing transparency for both the provider and consumer.

1.2 A Brief History of Cloud Technology

The concept of utility computing, where computing power is sold like electricity, dates back to the 1960s with the advent of time-sharing systems. These early systems allowed multiple users to access a single mainframe computer simultaneously, effectively sharing its resources and laying the intellectual groundwork for resource pooling and multi-tenancy.

The modern era of cloud computing, however, began in the early 2000s. The key turning point was the launch of Amazon Web Services (AWS) in 2006, which initially offered simple storage services (S3) and later introduced Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2). EC2 allowed users to rent virtual servers by the hour, marking the first widely available, scalable, and pay-as-you-go IaaS offering. This innovation, driven by Amazon’s need to monetize its massive, underutilized internal infrastructure, quickly catalyzed the industry. Soon after, other major players, including Google (Google Cloud Platform) and Microsoft (Azure), entered the market, leading to the current landscape dominated by these “hyperscalers.”

1.3 Cloud Deployment Models

Cloud services are deployed in various ways to meet diverse organizational needs for control, security, and cost. The three primary models are public, private, and hybrid.

| Deployment Model | Ownership & Management | Key Characteristics | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Cloud | Owned and operated by a third-party cloud service provider (CSP). | Resources are shared among multiple tenants (multi-tenancy). High elasticity and low initial cost. | General-purpose applications, web hosting, development/testing. |

| Private Cloud | Dedicated to a single organization. Can be on-premises or hosted externally. | Greater control over infrastructure, enhanced security, and compliance. | Highly regulated industries, sensitive data, predictable workloads. |

| Hybrid Cloud | A combination of two or more distinct cloud infrastructures (private and public) that remain unique entities but are bound together by proprietary or standardized technology. | Flexibility to move workloads between environments (cloud bursting). Balances control with scalability. | Disaster recovery, seasonal spikes in demand, legacy integration. |

The emergence of Multi-Cloud architecture, where an organization uses services from multiple public cloud providers (e.g., AWS for compute and Azure for identity), is a growing trend. This strategy aims to avoid vendor lock-in and leverage best-of-breed services, though it introduces significant complexity in management and networking.

Chapter 2: The Service Model Stack (IaaS, PaaS, SaaS)

The cloud service models define the level of abstraction and management provided by the cloud vendor versus the responsibility retained by the customer. This hierarchy is often visualized as a stack, with each layer building upon the one below it.

2.1 The Cloud Service Hierarchy: Who Manages What?

The simplest way to understand the difference is to compare the traditional on-premises model to the three main cloud service models:

| Component | On-Premises | IaaS | PaaS | SaaS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications | Customer | Customer | Customer | Vendor |

| Data | Customer | Customer | Customer | Customer |

| Runtime | Customer | Customer | Vendor | Vendor |

| Operating System | Customer | Customer | Vendor | Vendor |

| Middleware | Customer | Customer | Vendor | Vendor |

| Virtualization | Customer | Vendor | Vendor | Vendor |

| Servers | Customer | Vendor | Vendor | Vendor |

| Storage | Customer | Vendor | Vendor | Vendor |

| Networking | Customer | Vendor | Vendor | Vendor |

Note: In the table, “Customer” means the customer manages the component, and “Vendor” means the cloud provider manages the component.

2.2 Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS)

IaaS provides the fundamental building blocks of cloud IT. It offers access to computing resources such as virtual machines (VMs), storage, and networks. The customer is responsible for managing the operating system, middleware, and applications, while the cloud provider manages the underlying infrastructure, including the hypervisor, servers, and physical data center.

A key component of IaaS is the Hypervisor, which is the software, firmware, or hardware that creates and runs virtual machines (VMs). The hypervisor allows a single physical server (the host) to run multiple isolated virtual machines (guests), each with its own operating system and resources. This technology is the engine behind resource pooling and the ability to provision compute on demand.

2.3 Platform as a Service (PaaS)

PaaS provides a complete development and deployment environment in the cloud, with resources that enable customers to deliver everything from simple cloud-based applications to sophisticated enterprise applications. The provider manages the operating system, runtime environment, and middleware, allowing the customer to focus exclusively on application development and data.

PaaS is highly valued for its ability to accelerate the development lifecycle. Developers can deploy code directly without worrying about patching the OS, managing load balancers, or configuring the underlying network. This abstraction layer significantly improves developer productivity and time-to-market.

2.4 Software as a Service (SaaS)

SaaS is the most abstract service model, providing ready-to-use applications over the internet, typically through a web browser. The customer has no control over the underlying infrastructure, operating system, or application capabilities, only the configuration settings specific to their use. Examples include customer relationship management (CRM) software, email services, and office productivity suites.

The defining characteristic of most SaaS offerings is multi-tenancy at the application layer. A single instance of the application runs on the provider’s infrastructure and serves multiple customers (tenants). This architecture allows the provider to achieve massive economies of scale, which translates into lower costs for the end-user.

Part II: The Inner Workings: Cloud Architecture and Core Technologies

Chapter 3: Cloud Architecture: Front-End and Back-End

Cloud architecture is the blueprint that dictates how all the components—hardware, software, networking, and storage—are integrated to deliver cloud services. It is fundamentally a distributed system divided into two main sections: the front-end and the back-end, connected by a network.

3.1 The Cloud Architecture Blueprint

- Front-End: This is the client-side infrastructure that users interact with. It includes the client device (laptop, mobile phone), the user interface (web browser, mobile app), and the client-side applications. The front-end is the mechanism through which users access and manage cloud services.

- Back-End: This is the “cloud” itself, comprising the vast network of servers, storage systems, and software that collectively form the data center. It is responsible for providing the services, managing resources, and ensuring security.

- The Network: The internet, or a dedicated private connection, acts as the middleware, facilitating the communication between the front-end and the back-end. This connection enables the on-demand delivery of services.

3.2 The Data Center: The Physical Foundation

The cloud is not an ethereal concept; it is a massive collection of physical data centers. Cloud providers strategically locate these data centers globally, organizing them into Regions and Availability Zones (AZs).

- Region: A geographical area that hosts multiple, isolated data centers.

- Availability Zone (AZ): One or more discrete data centers with redundant power, networking, and connectivity, housed in separate facilities. AZs are physically isolated from each other to prevent a disaster in one from affecting the others, providing high availability and fault tolerance.

Within the data center, the physical infrastructure consists of thousands of servers mounted in racks, connected by a high-speed, low-latency network fabric. This fabric, often based on technologies like InfiniBand or high-speed Ethernet, ensures that compute and storage resources can communicate efficiently, which is critical for the performance of distributed applications.

3.3 Resource Pooling and Multi-Tenancy

The ability of the cloud to offer “unlimited” resources stems from two core concepts: resource pooling and multi-tenancy.

Resource Pooling is the aggregation of a provider’s computing resources (CPU, memory, storage, network bandwidth) into a single, massive pool. This pool is then dynamically allocated to multiple consumers. This allows the provider to achieve high utilization rates, as the peak demand of one customer is offset by the low demand of another.

Multi-Tenancy is the architecture where a single instance of a software application or infrastructure component serves multiple customers (tenants). In IaaS, this means multiple virtual machines belonging to different customers can run on the same physical server, securely isolated by the hypervisor. In PaaS and SaaS, the isolation is handled at the application or platform layer. Secure isolation is paramount, ensuring that one tenant’s data and operations are completely invisible and inaccessible to others.

Chapter 4: Virtualization and Containerization

The core mechanism that enables resource pooling and multi-tenancy is virtualization, which has been augmented by the more lightweight approach of containerization.

4.1 Deep Dive into Virtualization

Virtualization is the process of creating a software-based, or virtual, representation of something, such as a server, storage device, network, or operating system. It works by inserting a layer of software, the hypervisor, between the physical hardware and the operating system.

- Hypervisors:

- Type 1 (Bare Metal): Runs directly on the host’s hardware to manage the hardware and guest operating systems. This is the type used by cloud providers (e.g., VMware ESXi, Xen, KVM). It offers superior performance and security.

- Type 2 (Hosted): Runs on a conventional operating system (OS) just like other computer programs. This is typically used for desktop virtualization (e.g., VirtualBox, VMware Workstation).

A Virtual Machine (VM) is a complete, isolated operating environment. It includes its own virtual hardware (CPU, memory, disk, network interface) and a full-fledged guest operating system. VMs provide strong isolation, making them ideal for running different operating systems or applications with conflicting dependencies on the same physical hardware.

4.2 The Rise of Containerization

Containerization offers a more lightweight form of virtualization. Unlike VMs, which virtualize the entire machine down to the hardware layer, containers virtualize the operating system.

- Containers vs. VMs: Containers share the host operating system’s kernel. This means they do not require a separate OS image for each application, resulting in a much smaller footprint, faster boot times (seconds vs. minutes), and higher density (more containers per physical server).

- Docker and Container Images: Technologies like Docker package an application and all its dependencies (libraries, configuration files) into a standardized unit called a container image. This image is highly portable, ensuring that the application runs consistently across any environment—from a developer’s laptop to a public cloud data center.

- Orchestration with Kubernetes: As the number of containers grows, managing them manually becomes impossible. Kubernetes is the de facto standard for container orchestration. It automates the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications, ensuring high availability, load balancing, and self-healing capabilities across a cluster of servers.

4.3 Serverless Computing: The Ultimate Abstraction

Serverless computing represents the highest level of abstraction in the cloud stack. The term is a misnomer; servers still exist, but the customer is completely absolved of all server management responsibilities. The cloud provider dynamically manages the allocation and provisioning of compute resources.

The primary model for serverless is Function as a Service (FaaS), where developers upload small, single-purpose code functions (e.g., a function to process an image upload). The provider executes this function only when a specific event triggers it (e.g., an HTTP request, a new file in storage). The customer pays only for the compute time consumed during the function’s execution, making it incredibly cost-efficient for event-driven and intermittent workloads. This model pushes the boundaries of elasticity, allowing applications to scale from zero to thousands of instances in seconds.

(End of Part II. The article will continue with Part III: Cloud Networking and Storage.)

Part III: Cloud Networking and Storage

Chapter 5: Cloud Networking: The Virtual Fabric

The network is the invisible, yet critical, component that binds the cloud together. Cloud networking is not just about physical cables and routers; it is a highly virtualized and software-defined environment that provides the necessary connectivity, isolation, and control for cloud resources.

5.1 Software-Defined Networking (SDN)

Software-Defined Networking (SDN) is the architectural approach that enables the cloud’s network flexibility. SDN decouples the network’s control plane (the logic that decides how traffic is routed) from the data plane (the hardware that forwards the traffic).

In a traditional network, the control and data planes are tightly integrated into physical devices like routers and switches. With SDN, the control plane is centralized in a software controller. This allows the cloud provider to program the network dynamically, enabling features like rapid provisioning of network segments, automated load balancing, and the creation of virtual networks for individual customers without touching physical hardware. This programmability is essential for the rapid elasticity characteristic of the cloud.

5.2 Virtual Private Clouds (VPCs)

A Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) is a logically isolated virtual network dedicated to a single customer within a public cloud. It allows the customer to define their own IP address range, create subnets, configure route tables, and set up network gateways, providing a familiar and secure networking environment.

Key components of a VPC include:

- Subnets: Segments of the VPC’s IP address range, typically mapped to an Availability Zone (AZ) for high availability.

- Route Tables: Rules that determine where network traffic from a subnet is directed.

- Network Access Control Lists (NACLs) and Security Groups: Stateful and stateless firewalls that control inbound and outbound traffic at the subnet and instance level, respectively, ensuring network security.

- Internet Gateways and Virtual Private Gateways: Mechanisms to connect the VPC to the public internet or to a customer’s on-premises data center via a secure VPN connection.

The VPC is the primary tool for achieving network isolation and control in the IaaS model, giving customers the illusion of owning a private data center network within the public cloud.

5.3 Load Balancing and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs)

To handle massive traffic volumes and ensure high availability, cloud architecture relies heavily on Load Balancers and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs).

A Load Balancer automatically distributes incoming application traffic across multiple targets, such as virtual servers, in multiple Availability Zones. This prevents any single server from becoming a bottleneck and ensures that if one server fails, traffic is seamlessly rerouted to healthy ones. Load balancers operate at different layers of the network stack: Layer 4 (TCP/UDP) for raw data distribution and Layer 7 (HTTP/HTTPS) for application-aware routing.

A CDN is a geographically distributed network of proxy servers and data centers. Its purpose is to provide high availability and high performance by distributing the service spatially relative to end-users. By caching static content (images, videos, stylesheets) at Edge Locations—data centers closer to the end-user—CDNs drastically reduce latency and the load on the main application servers.

Chapter 6: Cloud Storage Technologies

Cloud storage is far more complex than a simple hard drive. Cloud providers offer a spectrum of storage services, each optimized for different use cases based on performance, cost, and access pattern. The three main types are object, block, and file storage.

6.1 Object Storage: Scalability and Durability

Object Storage is the foundation for massive, unstructured data in the cloud. Data is stored as discrete units called objects, which are kept in flat structures (buckets) rather than a hierarchical file system. Each object is associated with a unique identifier and rich, user-defined metadata.

- Characteristics: Object storage is designed for extreme scalability (petabytes and beyond) and high durability (often 99.999999999% or “eleven nines”). It is accessed via APIs (e.g., RESTful HTTP) and is ideal for data that is written once and read many times.

- Use Cases: Data lakes, backups, archives, static website hosting, and media content delivery.

- Mechanism: Durability is achieved through techniques like Erasure Coding and Replication, where data is fragmented and distributed across multiple physical devices and Availability Zones, ensuring that the loss of several disks or even an entire data center does not result in data loss.

6.2 Block Storage: High Performance for Compute

Block Storage is the closest analog to a traditional hard drive. Data is stored in fixed-size blocks, and the storage volume is presented to a virtual machine as a raw, unformatted disk. The operating system on the VM manages the file system.

- Characteristics: Block storage offers low latency and high Input/Output Operations Per Second (IOPS), making it suitable for transactional workloads.

- Use Cases: Boot volumes for virtual machines, relational databases, and any application requiring frequent, random read/write access.

- Mechanism: These volumes are typically provisioned from high-speed Solid-State Drives (SSDs) and are network-attached, meaning they can be detached from one VM and attached to another within the same AZ.

6.3 File Storage: Shared Access and Legacy Systems

File Storage provides a shared file system that can be mounted and accessed concurrently by multiple virtual machines using standard protocols like Network File System (NFS) or Server Message Block (SMB).

- Characteristics: It is designed for use cases where multiple compute instances need to read and write to the same shared data set simultaneously, maintaining file-level locking and consistency.

- Use Cases: Content management systems, shared development environments, and legacy applications that rely on a shared file system interface.

6.4 Managed Database Services (DBaaS)

Database as a Service (DBaaS) is a critical PaaS offering. The cloud provider manages the operational aspects of the database, including provisioning, patching, backups, scaling, and high availability.

- Types: Cloud providers offer managed services for both Relational Databases (e.g., MySQL, PostgreSQL, proprietary SQL engines) and Non-Relational (NoSQL) Databases (e.g., document, key-value, graph databases).

- Benefits: DBaaS abstracts away the complex and time-consuming tasks of database administration, allowing developers and organizations to focus on data modeling and application logic. Features like automated failover and read replicas are built-in, ensuring business continuity.

(End of Part III. The article will continue with Part IV: Security, Operations, and the Future.)

Part IV: Security, Operations, and the Future

Chapter 7: Cloud Security and the Shared Responsibility Model

Security in the cloud is a partnership, formalized by the Shared Responsibility Model. This model is arguably the single most important concept for cloud customers to understand, as it clearly delineates which security tasks are the responsibility of the cloud provider and which fall to the customer.

7.1 The Shared Responsibility Model: A Fundamental Concept

The core tenet of the model is: The Cloud Provider is responsible for the security of the cloud, and the Customer is responsible for the security in the cloud.

| Responsibility | Cloud Provider (Security of the Cloud) | Customer (Security in the Cloud) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Security | Data centers, physical hardware, and infrastructure. | N/A |

| Infrastructure | Global infrastructure, regions, availability zones, network fabric. | N/A |

| Virtualization | Hypervisor, host operating system, and isolation between tenants. | N/A |

| Operating System | N/A (Customer’s responsibility in IaaS) | Guest OS configuration, patching, and hardening. |

| Application & Data | N/A | Data encryption, access control, network configuration (VPC, firewalls). |

| Identity & Access | N/A | User and access management (IAM), multi-factor authentication (MFA). |

The exact boundary shifts depending on the service model:

- IaaS: The customer has the greatest responsibility, managing everything from the operating system up.

- PaaS: The provider takes on more responsibility, managing the OS, runtime, and middleware. The customer focuses on application code and data.

- SaaS: The provider manages almost everything, and the customer’s responsibility is limited to user access, data classification, and configuration.

7.2 Identity and Access Management (IAM)

Identity and Access Management (IAM) is the cornerstone of cloud security. It is the framework that controls who (or what) can access resources and what actions they can perform.

IAM systems are built on the principle of Least Privilege, meaning that a user or service should only be granted the minimum permissions necessary to perform their job. Key components include:

- Users and Groups: Human and machine identities are organized into groups to simplify permission management.

- Roles: A set of permissions that can be assumed by a user or service. This is a temporary credential mechanism that avoids long-lived access keys.

- Policies: JSON or YAML documents that explicitly define the allowed or denied actions on specific resources.

The implementation of Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) is a mandatory best practice, significantly reducing the risk of compromised credentials.

7.3 Data Protection and Compliance

Data protection in the cloud revolves around two states: Data in Transit and Data at Rest.

- Data in Transit: Data moving across the network is protected using protocols like TLS/SSL (Transport Layer Security), which encrypts the communication channel between the client and the server.

- Data at Rest: Data stored in cloud storage services (object, block, file) is protected using AES-256 encryption. Cloud providers offer options for provider-managed keys or customer-managed keys, giving the customer control over the encryption process.

Regulatory Compliance is a major driver for cloud security. Organizations must adhere to various standards and regulations based on their industry and location, such as:

- GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation): For handling personal data of EU citizens.

- HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act): For protecting sensitive patient health information in the US.

- PCI DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard): For handling credit card information.

Cloud providers undergo rigorous third-party audits to certify their infrastructure against these standards, but the customer remains responsible for configuring their applications and data to be compliant within that infrastructure.

Chapter 8: Cloud Operations and Advanced Concepts

The cloud has not only changed where applications run but also how they are built, deployed, and managed.

8.1 Cloud-Native Development and Microservices

The shift to the cloud has accelerated the adoption of Cloud-Native principles, which advocate for building and running applications that fully exploit the cloud computing model.

- Microservices: Instead of building a single, monolithic application, the microservices architecture structures an application as a collection of small, independent, and loosely coupled services. Each service runs its own process, communicates via lightweight mechanisms (like APIs), and can be deployed and scaled independently. This architecture is perfectly suited for containerization and Kubernetes orchestration.

- DevOps and CI/CD: The cloud facilitates the DevOps culture, which emphasizes collaboration between development and operations teams. Continuous Integration/Continuous Delivery (CI/CD) pipelines automate the process of building, testing, and deploying applications, allowing for rapid, frequent, and reliable software releases.

8.2 Infrastructure as Code (IaC)

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is the practice of managing and provisioning infrastructure through machine-readable definition files, rather than physical hardware configuration or interactive configuration tools.

Tools like Terraform and CloudFormation allow developers to define their entire cloud environment—VPCs, subnets, virtual machines, databases, and security rules—in code. This code is version-controlled, repeatable, and auditable, eliminating manual errors and ensuring that the infrastructure is always deployed in a consistent and predictable state. IaC is a cornerstone of modern cloud operations.

8.3 FinOps: Cloud Financial Management

The ease of provisioning resources in the cloud can lead to uncontrolled spending. FinOps (Cloud Financial Operations) is an evolving operational framework that brings financial accountability to the variable spend model of the cloud.

FinOps is a cultural practice that requires technology, finance, and business teams to collaborate on data-driven spending decisions. Key strategies include:

- Cost Visibility: Using cloud provider tools to track and allocate costs to specific teams or projects.

- Optimization: Employing strategies like Reserved Instances (RIs) or Savings Plans for predictable workloads, and using Spot Instances for fault-tolerant, non-critical workloads to achieve significant discounts.

- Right-Sizing: Continuously monitoring resource utilization and scaling down or terminating underutilized resources.

8.4 The Future of Cloud Computing

The cloud continues to evolve rapidly, pushing computing power closer to the user and integrating new technologies:

- Edge Computing: Moving compute and storage resources out of the centralized data center and closer to the data source (e.g., IoT devices, mobile phones). This reduces latency and bandwidth requirements for real-time applications.

- AI/ML as a Service: Cloud providers are democratizing Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning by offering fully managed services for data preparation, model training, and deployment, making advanced capabilities accessible to a wider audience.

- Serverless and FaaS Dominance: The trend toward greater abstraction will continue, with more applications being built entirely on serverless and managed services, further reducing the operational burden on businesses.

Part V: Conclusion and References

Chapter 9: Summary and References

9.1 Conclusion: The Cloud as the New Normal

Cloud technology is not merely a technological trend; it is the fundamental infrastructure of the modern digital economy. It is a complex, multi-layered system built upon decades of innovation in virtualization, networking, and distributed systems. From the physical isolation of Availability Zones to the logical isolation of VPCs and the ephemeral nature of serverless functions, the cloud works by abstracting complexity and pooling resources to deliver unprecedented scale, elasticity, and cost efficiency.

Understanding the inner workings—from the hypervisor that enables IaaS to the Shared Responsibility Model that governs security—is essential for any organization seeking to harness its full potential. The cloud has become the new normal, providing the platform for the next generation of global innovation.

Be First to Comment