A Comprehensive Analysis

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence has created an urgent need for reliable methods to evaluate AI system performance. Industrial benchmark models have emerged as the primary means of comparing capabilities across different AI systems, yet they represent a complex landscape of competing methodologies, inherent limitations, and ongoing debates about what truly constitutes “intelligence” in machines.

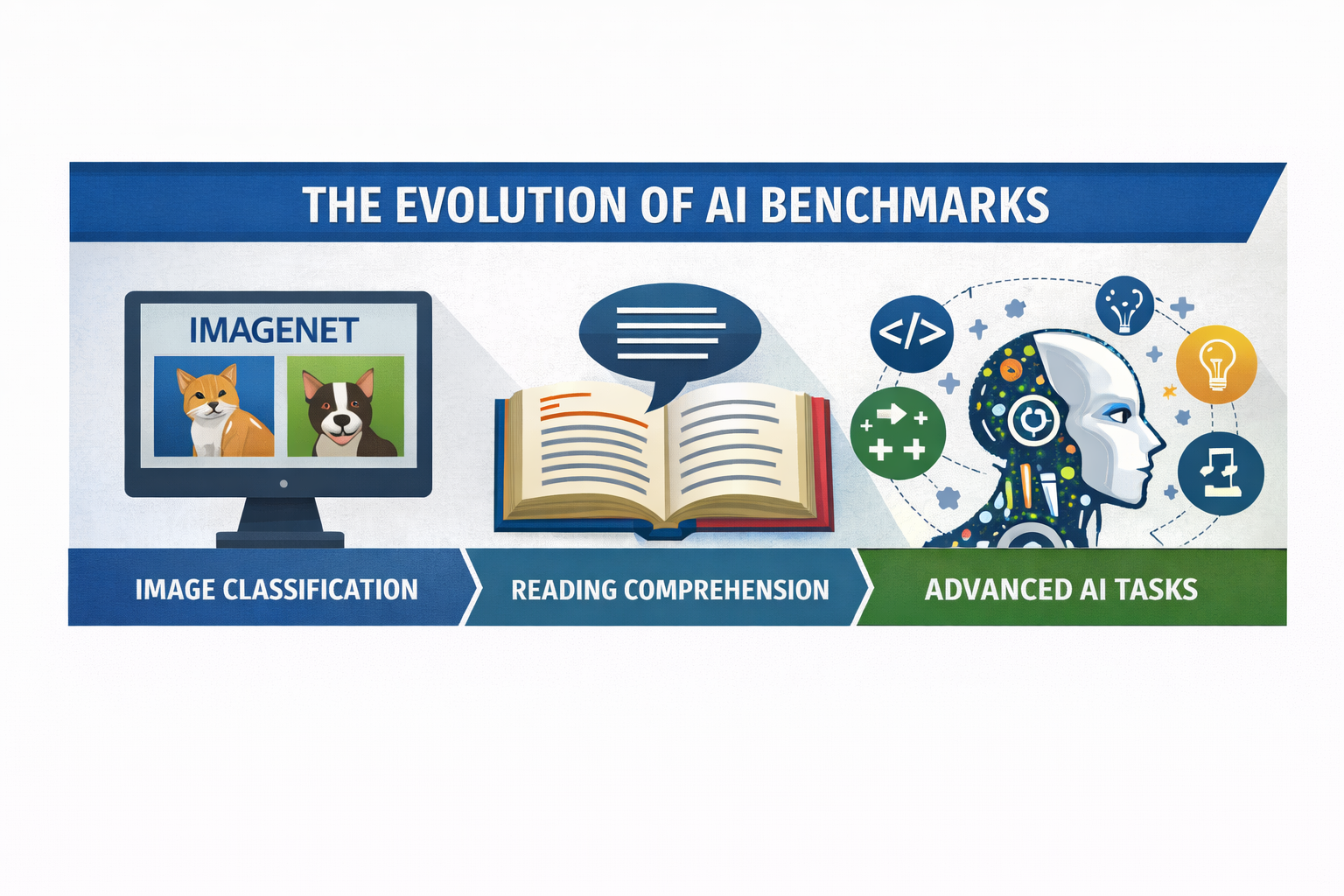

The Evolution of AI Benchmarking

The history of AI benchmarking reflects the field’s evolving ambitions. Early benchmarks focused on narrow, well-defined tasks such as image classification on ImageNet or language understanding through reading comprehension tests. These benchmarks served their purpose well, providing clear metrics that drove competition and progress. However, as AI systems have grown more sophisticated, particularly with the rise of large language models and multimodal systems, the benchmark landscape has necessarily become more complex.

Modern benchmarks attempt to capture a broader spectrum of cognitive abilities. They evaluate not just pattern recognition or memorization, but reasoning, common sense understanding, mathematical problem-solving, code generation, and even creative capabilities. This shift reflects both the expanding capabilities of AI systems and a growing recognition that narrow task performance may not translate to general utility.

Major Benchmark Categories and Their Purposes

Contemporary AI benchmarks can be broadly categorized into several overlapping domains, each targeting different aspects of system performance.

Language Understanding and Reasoning Benchmarks form perhaps the largest category. MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) tests knowledge across 57 subjects ranging from mathematics and science to humanities and social sciences. It has become a standard reference point for evaluating general knowledge, though critics note it primarily measures memorization rather than genuine understanding. The benchmark consists of multiple-choice questions that span elementary through professional difficulty levels.

GPQA (Graduate-Level Google-Proof QA) represents an attempt to create more challenging evaluation criteria. Developed by domain experts with PhD-level knowledge, these questions are designed to be difficult even for specialists to answer without extensive research. The “Google-proof” designation indicates that answers cannot be easily found through simple web searches, theoretically testing deeper reasoning rather than retrieval capabilities.

Mathematical and Logical Reasoning receives dedicated attention through benchmarks like GSM8K, which contains grade-school level math word problems, and MATH, which includes competition-level mathematical problems spanning algebra, geometry, number theory, and calculus. These benchmarks are particularly valuable because mathematical reasoning requires precise logical steps and offers objectively verifiable answers, making them less susceptible to subjective interpretation than many language tasks.

Coding Benchmarks have gained prominence as AI systems are increasingly deployed in software development contexts. HumanEval, developed by OpenAI, presents function-level programming challenges where models must generate Python code to pass specific test cases. More recently, SWE-bench has emerged as a more realistic evaluation, requiring models to solve actual GitHub issues from real-world repositories. This benchmark better captures the complexity of practical software engineering, including understanding existing codebases, debugging, and making contextually appropriate changes.

Multimodal Benchmarks assess systems that process multiple input types. MMMU (Massive Multi-discipline Multimodal Understanding) combines images with text across various academic disciplines, requiring models to interpret diagrams, charts, photographs, and other visual information alongside textual questions. As AI systems become increasingly multimodal, these benchmarks have become critical for evaluating real-world applicability.

Agent and Tool-Use Benchmarks represent a newer category focused on evaluating AI systems’ ability to interact with external tools, APIs, and environments. These benchmarks assess whether models can break down complex tasks, select appropriate tools, and execute multi-step workflows. Examples include WebArena, which tests agents’ ability to complete tasks on websites, and various API-usage benchmarks that evaluate function-calling capabilities.

The Benchmark Arms Race and Its Consequences

The relationship between AI development and benchmarking has become cyclical and somewhat problematic. As new benchmarks emerge, they initially provide challenging evaluation criteria that differentiate system capabilities. However, AI developers naturally optimize for these benchmarks, and performance rapidly saturates. This creates what some researchers call “benchmark overfitting,” where systems become exceptionally good at specific evaluation criteria without necessarily improving in genuine general capability.

This pattern has played out repeatedly. ImageNet accuracy, once a primary metric for computer vision progress, reached superhuman levels years ago but stopped meaningfully differentiating advanced systems. Similarly, many language understanding benchmarks designed just a few years ago now show near-ceiling performance from multiple models, forcing the development of increasingly challenging alternatives.

The response has been a continuous escalation in benchmark difficulty. MMLU begat MMLU-Pro, which added more challenging questions and more answer options to reduce guessing success rates. Simple coding challenges gave way to complex repository-level tasks. Basic question-answering evolved into multi-step reasoning problems requiring extensive context.

This arms race creates several concerns. First, increasingly difficult benchmarks may test capabilities that have limited real-world relevance. A model that performs slightly better on PhD-level physics questions may not actually be more useful for most practical applications. Second, the focus on benchmark performance can distort development priorities, leading companies to optimize for metrics rather than genuine utility. Third, as benchmarks become more complex and specialized, they become harder to replicate and verify, potentially reducing transparency in the field.

Contamination and Validity Concerns

One of the most significant challenges facing modern benchmarks is data contamination. Large language models are trained on massive portions of the internet, and benchmark questions inevitably appear in training data, either directly or in similar forms. This creates a fundamental problem: high benchmark scores may reflect memorization rather than genuine capability.

The issue is particularly acute for publicly available benchmarks. Once a benchmark dataset is published online, it becomes part of the crawlable web and likely gets incorporated into future training datasets. This has led to the development of “closed” or “private” benchmarks that are never released publicly, with evaluation happening through controlled API access. However, this approach sacrifices reproducibility and transparency, making it difficult for the research community to verify claims or build upon results.

Some recent efforts attempt to address contamination through constantly refreshing evaluation sets. LiveBench, for instance, introduces new questions monthly based on recent events and information that could not have been in training data. Similarly, some benchmarks now include contamination detection procedures, analyzing whether models show suspiciously high performance on specific subsets of questions.

The Problem of Evaluation Itself

Beyond contamination, the fundamental question of how to evaluate AI responses remains challenging, particularly for open-ended tasks. Multiple-choice questions provide clear right and wrong answers but may not capture the nuanced capabilities of modern systems. Conversely, open-ended generation tasks are closer to real-world usage but difficult to score objectively.

This has led to the controversial practice of using AI systems to evaluate other AI systems, sometimes called “LLM-as-a-judge.” Strong language models like GPT-4 or Claude evaluate responses from other models, providing scores or comparisons based on criteria like helpfulness, accuracy, and coherence. While this approach offers scalability and can capture nuanced quality differences, it introduces its own biases and limitations. Models may favor responses stylistically similar to their own outputs, and any flaws in the evaluating model propagate to the evaluation process itself.

Human evaluation remains the gold standard but is expensive, time-consuming, and itself subject to inconsistency across evaluators. Arena-style evaluations, where users vote on blind comparisons between model responses, have emerged as a complementary approach. Platforms like Chatbot Arena collect thousands of human preference judgments, providing aggregate rankings that may better reflect real-world user satisfaction than traditional benchmarks. However, these too have limitations, including potential voter bias, the difficulty of ensuring representative user samples, and the challenge of evaluating specialized capabilities that most users cannot accurately judge.

The Question of What We’re Actually Measuring

A deeper critique of modern benchmarks questions whether they measure what we claim they do. High performance on reading comprehension tests may reflect sophisticated pattern matching rather than genuine understanding. Strong results on reasoning benchmarks might demonstrate statistical learning of common reasoning patterns rather than true logical capability. Code generation success could rely on memorizing common programming patterns rather than understanding computational principles.

This philosophical concern connects to broader debates about the nature of intelligence and understanding. If a system produces correct answers through mechanisms fundamentally different from human cognition, does it truly “understand” or “reason”? Benchmarks generally take a pragmatic, behaviorist approach, measuring outputs rather than internal processes. While this approach has practical utility, it leaves open questions about whether benchmark performance actually translates to robust, generalizable capabilities.

The distinction becomes important when systems encounter distribution shifts or novel scenarios. A model might perform excellently on standard benchmarks while failing unpredictably on slight variations or real-world applications that deviate from benchmark patterns. This brittleness suggests that benchmark performance, while informative, provides an incomplete picture of system capabilities.

Emerging Approaches and Future Directions

Recognition of traditional benchmarks’ limitations has sparked innovation in evaluation methodologies. Dynamic benchmarks that continuously update with new content aim to prevent memorization and maintain challenge levels. Benchmarks designed to test robustness and out-of-distribution generalization examine how systems perform when faced with unfamiliar variations of tasks they’ve nominally mastered.

Process-based evaluation represents another emerging direction. Rather than solely judging final answers, these approaches assess the reasoning process models employ to reach conclusions. This might involve evaluating intermediate steps in mathematical problem-solving or assessing the logical coherence of multi-step reasoning chains. While challenging to implement at scale, process-based evaluation may better capture genuine capability.

Real-world task benchmarks attempt to bridge the gap between controlled evaluations and practical utility. Rather than simplified, isolated tasks, these benchmarks present scenarios drawn from actual use cases, complete with the ambiguity, complexity, and context that characterize real applications. SWE-bench’s use of actual GitHub issues exemplifies this approach, as do benchmarks based on customer service interactions, document processing workflows, or scientific research tasks.

Safety and alignment benchmarks have also gained prominence. These evaluate not just capability but whether systems behave in accordance with human values and intentions. They test for harmful outputs, bias, truthfulness, and resistance to adversarial manipulation. As AI systems are deployed in sensitive applications, these evaluations become as important as traditional performance metrics.

The Industrial Perspective

From an industrial standpoint, benchmarks serve multiple purposes beyond pure scientific evaluation. They provide marketing-friendly metrics for comparing products, guide resource allocation in development organizations, and help customers make informed decisions about which systems to deploy. However, this creates tension between benchmarks’ scientific and commercial functions.

Companies face pressure to achieve state-of-the-art benchmark results, which can drive rapid progress but also encourages gaming metrics. Minor improvements on popular benchmarks receive disproportionate attention, while innovations that don’t readily translate to benchmark gains may be undervalued. Some organizations have been accused of selectively reporting benchmark results, highlighting favorable metrics while downplaying others.

The concentration of benchmark performance among a few leading organizations raises additional concerns. If only a handful of well-resourced companies can compete on frontier benchmarks, this may reduce the diversity of approaches and perspectives in AI development. Conversely, open benchmarks democratize evaluation, allowing smaller research groups and organizations to meaningfully contribute to progress assessment.

Recommendations for Interpretation

Given these complexities, how should benchmark results be interpreted? Several principles emerge from critical analysis of the field.

First, no single benchmark provides a complete picture. Strong performance on one evaluation may not generalize to others, and comprehensive assessment requires examining multiple diverse benchmarks. Organizations should be wary of over-emphasizing any particular metric.

Second, benchmark results should be contextualized by understanding what specific benchmarks do and don’t measure. A model excelling at multiple-choice academic questions may still struggle with practical tasks requiring nuanced judgment or domain adaptation. Users should align benchmark performance with their specific use case requirements.

Third, the margin of error and statistical significance matter. Small differences in benchmark scores often fall within noise and should not be over-interpreted. Similarly, aggregate benchmark scores can mask important variations in performance across subtasks or domains.

Fourth, qualitative evaluation remains essential. Interacting with systems directly, examining failure cases, and testing robustness through adversarial examples provides insights that quantitative benchmarks alone cannot capture. The growing popularity of arena-style evaluations reflects recognition that aggregate human judgment captures dimensions traditional benchmarks miss.

Finally, benchmark performance should be considered alongside other factors like efficiency, cost, latency, safety characteristics, and ease of use. A system with slightly lower benchmark scores but better reliability, lower operational costs, or superior safety properties might be preferable for many applications.

Conclusion

Modern AI industrial benchmarks represent an imperfect but essential tool for measuring and driving progress in artificial intelligence. They have undeniably catalyzed rapid advancement, providing clear targets for optimization and enabling meaningful comparisons between systems. However, they also suffer from significant limitations, including contamination concerns, gaming incentives, the challenges of evaluating open-ended capabilities, and philosophical questions about what they actually measure.

The field continues to evolve, with researchers developing more sophisticated evaluation methodologies and grappling with fundamental questions about how to assess increasingly capable AI systems. The tension between standardized, reproducible metrics and real-world utility remains unresolved, as does the question of whether any benchmark suite can truly capture general intelligence or practical usefulness.

For now, benchmarks serve best as one input among many in assessing AI systems. They provide valuable quantitative signals but require careful interpretation, contextual understanding, and complementary evaluation approaches. As AI capabilities continue to advance, the benchmark landscape will undoubtedly continue adapting, though the fundamental challenges of evaluation will likely persist. The goal remains developing evaluation methodologies that are rigorous, meaningful, difficult to game, and genuinely predictive of real-world value. A goal that continues to drive innovation in AI assessment methodology.

Be First to Comment