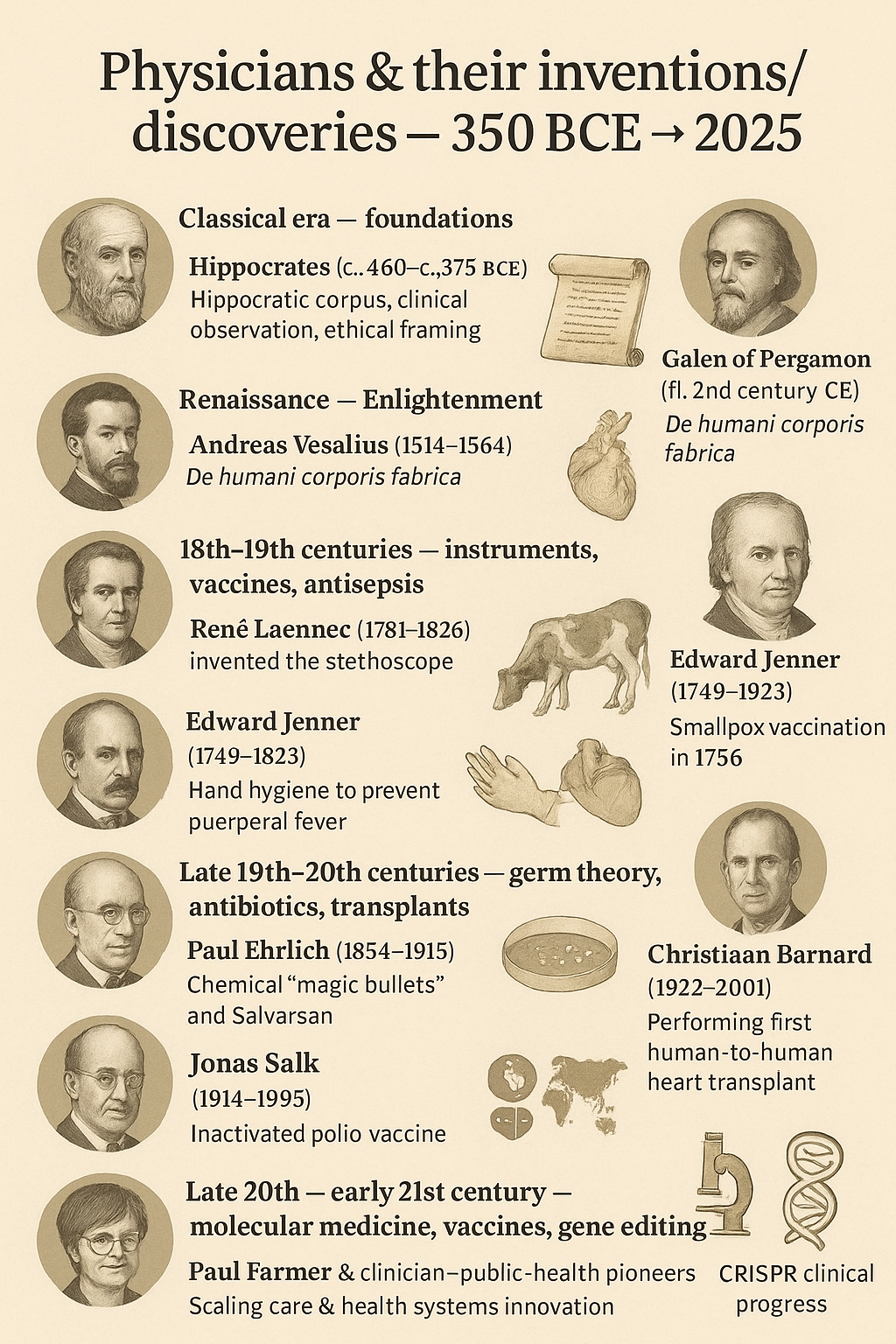

Throughout history, the relentless pursuit of understanding the human body and combating disease has driven countless physicians and scientists to innovate. From ancient civilizations laying the groundwork for medical ethics and surgical techniques to modern breakthroughs in genomics and advanced therapies, each era has witnessed transformative discoveries. This article delves into the remarkable journey of medical progress, highlighting pivotal figures and their inventions that have profoundly shaped healthcare from 350 BCE to the present day.

Ancient Period (350 BCE – 4th Century CE)

Early Pioneers and Foundational Concepts

The foundations of medicine were laid in ancient civilizations, where early physicians began to move beyond supernatural explanations for illness, embracing observation and rational inquiry. This era saw the emergence of ethical medical practices, sophisticated surgical techniques, and the development of early pharmacological knowledge.

Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE, Greek), often revered as the “Father of Medicine,” revolutionized medical thought by emphasizing natural causes for diseases. His enduring legacy includes the establishment of ethical standards through the Hippocratic Oath, a pledge that continues to guide medical professionals today. The collective works attributed to him, known as the Hippocratic Corpus, provided a systematic approach to clinical observation and rational medicine, moving away from superstitious beliefs.

In ancient India, Sushruta (c. 7th Century BCE), considered one of the earliest surgeons, authored The Compendium of Suśruta. This seminal work meticulously detailed numerous surgical procedures, instruments, and concepts, including advanced techniques like rhinoplasty (plastic surgery of the nose) and lithotomy (surgical removal of stones). His contributions underscore the sophisticated surgical knowledge present in ancient Indian medicine.

Another principal contributor to Ayurveda was Charaka (c. 6th–2nd Century BCE, Indian). His Charaka Samhita presented a rational approach to understanding the causes and cures of diseases, emphasizing objective clinical examination methods. This text remains a cornerstone of Ayurvedic medicine, highlighting the importance of systematic diagnosis.

The Alexandrian school of anatomy produced significant figures like Herophilus (3rd Century BCE, Greek), who is often deemed the first anatomist. His pioneering dissections led to detailed studies of the nervous system, where he distinguished between sensory and motor nerves, and meticulously examined the brain. He also made significant contributions to the anatomy of the eye and established much of the medical terminology still in use. Alongside him, Erasistratus (3rd Century BCE, Greek) further advanced anatomical knowledge by studying the brain, differentiating between the cerebrum and cerebellum, and investigating the physiology of the brain, heart, eyes, and the vascular, nervous, respiratory, and reproductive systems.

In China, Bian Que (4th Century BCE) emerged as the earliest known Chinese physician, credited with pioneering acupuncture and pulse diagnosis. His methods laid the groundwork for traditional Chinese medicine, which continues to be practiced globally.

The Roman period saw contributions from Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BCE – c. 50 CE), who authored De Medicina, a comprehensive medical encyclopedia. This work covered a wide range of medical topics, including diet, pharmacy, and surgery, serving as an important reference for centuries.

Pedanius Dioscorides (1st Century CE, Greek) wrote De Materia Medica, a foundational pharmacopoeia that remained in use for over 1600 years. This extensive text detailed numerous herbal remedies and their uses, becoming an indispensable resource for pharmacists and physicians.

Perhaps the most accomplished medical researcher of antiquity was Galen (129–c. 216 CE, Greek/Roman). His clinical medicine was rooted in meticulous observation and extensive experience. His comprehensive medical philosophy, which integrated anatomical, physiological, and pharmacological knowledge, dominated Western medicine throughout the Middle Ages and until the beginning of the modern era.

Other notable figures include Antyllus (2nd Century CE, Greek), a prominent surgeon whose innovative treatment of aneurysms became standard practice until the 19th century. Soranus of Ephesus (1st–2nd Century CE, Greek) was a renowned gynecologist whose work significantly influenced obstetrics and gynecology, providing detailed insights into women’s health.

The institutionalization of healthcare also began in this period. Fabiola (4th Century CE, Roman) founded the first hospital in Latin Christendom in Rome, marking a significant step towards organized patient care. Following her example, Basil of Caesarea (4th Century CE, Roman) established the Basileias in Cappadocia, an institution with multiple buildings dedicated to patients, nurses, physicians, workshops, and schools, further advancing the concept of structured healthcare delivery.

Post-Classical Period (5th Century CE – 15th Century CE)

Bridging Ancient Knowledge and New Discoveries

The Post-Classical period, often referred to as the Middle Ages, witnessed the preservation and expansion of ancient medical knowledge, particularly in the Islamic world. While Europe experienced a decline in scientific inquiry after the fall of the Roman Empire, Islamic scholars translated, studied, and built upon Greek and Roman texts, leading to significant advancements.

Paul of Aegina (7th Century CE, Byzantine) authored the Medical Compendium in Seven Books, a significant work that summarized the medical knowledge of his time and served as a crucial link between ancient and medieval medicine.

In the Islamic Golden Age, Al-Razi (Rhazes) (9th-10th Century CE, Persian) was a prolific physician and alchemist. His contributions included pioneering work in pediatrics and making the first clear distinction between smallpox and measles in his influential work, al-Hawi. This differentiation was critical for public health and disease management.

Al-Majusi (10th Century CE, Persian) became famous for his Kitab al-Maliki, or Complete Book of the Medical Art, a comprehensive textbook that covered both medicine and psychology. This work demonstrated a holistic approach to health and disease.

Al-Zahrawi (10th-11th Century CE, Arab Andalusian) is widely regarded as the founder of early surgical and medical instruments. His monumental work, Kitab al-Tasrif, meticulously documented numerous surgical procedures and illustrated various surgical instruments. This text profoundly influenced European surgery for centuries, introducing many techniques that are still recognizable today.

One of the most influential figures of this era was Ibn Sina (Avicenna) (10th-11th Century CE, Persian), whose The Canon of Medicine became a medical encyclopedia of unparalleled importance. This work synthesized Greek and Arabic medical traditions and served as a standard textbook in European universities until the 18th century, shaping medical education and practice across continents.

A significant challenge to established Galenic views came from Ibn an-Nafis (13th Century CE, Arab), who accurately suggested that the right and left ventricles of the heart are separate and described the pulmonary and coronary circulation. His insights were centuries ahead of their time and paved the way for a more accurate understanding of cardiovascular physiology.

Ibn al-Baytar (12th-13th Century CE, Arab Andalusian) made extensive contributions to botany and pharmacy. He wrote comprehensively on medicinal plants and their uses, and also studied animal anatomy and veterinary medicine, expanding the scope of medical knowledge.

In Europe, Roger Bacon (13th Century CE, English), a polymath, contributed ideas on experimental science and proposed the use of convex lens spectacles for treating long-sightedness, an early recognition of optical correction.

Mondino de Luzzi (13th-14th Century CE, Italian) marked a turning point in anatomical study by carrying out the first systematic human dissections since Herophilus and Erasistratus, nearly 1500 years earlier. His work significantly advanced anatomical knowledge and laid the groundwork for Renaissance anatomists.

Guy de Chauliac (14th Century CE, French) was a prominent surgeon who not only documented the devastating impact of the Black Death but also advocated for an experimental approach to medicine. His surgical texts were highly influential and demonstrated a pragmatic approach to patient care during a challenging period.

Early Modern Period (16th Century CE – 18th Century CE)

Renaissance and the Dawn of Modern Science

The Early Modern Period was a time of profound intellectual and scientific transformation, characterized by the Renaissance, the Age of Exploration, and the Scientific Revolution. In medicine, this era saw a critical re-evaluation of ancient doctrines, the rise of empirical observation, and groundbreaking discoveries that challenged long-held beliefs.

Paracelsus (1493–1541), a controversial but influential figure, rejected traditional medical theories and pioneered the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine. He emphasized the relationship between medicine and surgery, advocating for a more holistic and experimental approach to healing. His radical ideas, though often met with resistance, laid some of the groundwork for modern pharmacology.

A pivotal moment in anatomical study came with Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564, Belgian). His monumental work, De Fabrica Corporis Humani (On the Fabric of the Human Body), published in 1543, meticulously corrected many Greek medical errors and revolutionized the study of human anatomy. Vesalius’s detailed illustrations and empirical observations earned him the title “founder of modern human anatomy,” fundamentally changing how the human body was understood.

Ambroise Paré (1510–1590), a French surgeon, made significant advancements in surgical wound treatment. He moved away from the brutal practice of cauterization with hot irons or boiling oil, instead advocating for ligatures to tie off blood vessels and more gentle wound care. His innovations dramatically improved patient outcomes and established him as a leading figure in surgical history.

In 1553, Miguel Servet described the circulation of blood through the lungs, a crucial step towards understanding the full circulatory system. This discovery, though initially suppressed, foreshadowed later, more comprehensive explanations.

The most definitive explanation of the circulatory system came from William Harvey (1578–1657, English). His seminal work, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (An Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Living Beings), published in 1628, accurately described how the heart pumps blood throughout the body in a closed system. This landmark work revolutionized physiology and laid the foundation for modern cardiovascular medicine.

Preventive medicine also saw early advancements. Giacomo Pylarini (1701) introduced smallpox inoculations to Europe, a practice that had been common in the East for centuries. This early form of immunization, though rudimentary, was a crucial step in controlling one of history’s most devastating diseases.

Surgical techniques continued to evolve with figures like Claudius Aymand (1736), who performed the first successful appendectomy, demonstrating the feasibility of removing an inflamed appendix. This procedure, once highly dangerous, became a life-saving intervention.

Naval health received a significant boost from James Lind (1747), who discovered that citrus fruits prevent scurvy. His controlled experiments on sailors demonstrated the efficacy of dietary interventions, leading to the widespread use of citrus on long voyages and virtually eradicating scurvy among seafarers.

A monumental achievement in preventive medicine was the development of the smallpox vaccination method by Edward Jenner (1796). Observing that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox were immune to smallpox, Jenner successfully inoculated a young boy with cowpox, demonstrating protection against smallpox. This discovery marked the birth of vaccinology and paved the way for the eradication of smallpox.

In the realm of chemistry and its medical applications, Joseph Priestley (1774) discovered several important gases, including nitrous oxide, nitric oxide, ammonia, hydrogen chloride, and oxygen. His work laid the groundwork for later medical applications, particularly in anesthesia and respiratory therapy.

Finally, William Withering (1785) published “An Account of the Foxglove,” providing the first systematic description of digitalis in treating dropsy (congestive heart failure). His meticulous observations and clinical trials established the therapeutic use of this powerful cardiac glycoside, which remains an important medication today.

Late Modern Period (19th Century CE – 20th Century CE)

Industrial Revolution and Scientific Breakthroughs

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed an explosion of scientific and technological advancements, driven by the Industrial Revolution and a deeper understanding of biology, chemistry, and physics. This era transformed medicine from an empirical art into a scientific discipline, leading to unprecedented improvements in public health and patient care.

At the dawn of the 19th century, Humphry Davy (1800) announced the anesthetic properties of nitrous oxide, paving the way for pain-free surgery. This was followed by Friedrich Sertürner (1803–1841), who first isolated morphine, marking a significant advance in pharmacology and pain management.

A revolutionary tool for clinical diagnosis emerged with René Laennec (1816), who invented the stethoscope. This simple yet ingenious device allowed physicians to listen to internal body sounds, greatly enhancing their ability to diagnose heart and lung conditions.

In the field of transfusion medicine, James Blundell (1818) performed the first successful human-to-human blood transfusion, a critical step towards saving lives through blood replacement therapy.

Hygiene and infection control became paramount with Ignaz Semmelweis (1847), who drastically reduced puerperal fever by introducing handwashing in obstetrics. His work, though initially met with resistance, laid the foundation for modern aseptic techniques.

The medical profession also saw significant social changes. Elizabeth Blackwell (1849) broke barriers by becoming the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States, opening doors for future generations of female physicians.

Technological innovations continued with Charles Gabriel Pravaz and Alexander Wood (1853), who invented the modern hypodermic syringe, enabling precise and sterile delivery of medications.

Modern nursing practices were established by Florence Nightingale (1854), whose pioneering work during the Crimean War transformed patient care and sanitation, significantly reducing mortality rates.

Louis Pasteur (1860s-1880s) made monumental contributions to microbiology and immunology. He disproved spontaneous generation, developed pasteurization to prevent food spoilage, and created vaccines for anthrax and rabies. His work solidified the germ theory of disease, fundamentally changing our understanding of infection.

Building on Pasteur’s work, Joseph Lister (1867) introduced antiseptic surgery using carbolic acid. This practice dramatically reduced post-operative infections and transformed surgical outcomes, making complex operations safer.

Robert Koch (1870s-1880s) further advanced the germ theory by identifying the anthrax and tuberculosis bacteria. His postulates provided a rigorous framework for proving the causal link between microorganisms and disease.

A new era of medical diagnostics began with Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1895), who discovered X-rays. This non-invasive imaging technique allowed physicians to visualize internal body structures, revolutionizing diagnosis and treatment planning.

In pharmacology, Felix Hoffmann (1897) synthesized aspirin, which became one of the most widely used drugs for pain relief and inflammation. The discovery of radioactivity by Marie Curie and Pierre Curie (1898), who isolated radium and polonium, paved the way for radiation therapy in cancer treatment.

The early 20th century brought further breakthroughs. Karl Landsteiner (1901) discovered blood groups, enabling safe blood transfusions and preventing life-threatening reactions. Frederick Banting and Charles Best (1921) isolated insulin, a life-saving treatment for diabetes that transformed a fatal disease into a manageable condition.

A pivotal moment in infectious disease control was Alexander Fleming’s (1928) discovery of penicillin, the first widely effective antibiotic. This accidental discovery ushered in the age of antibiotics, dramatically reducing mortality from bacterial infections. Gerhard Domagk (1935) further expanded the arsenal against infections with the discovery of sulfonamide drugs, another class of antibiotics.

The mid-20th century saw major advances in vaccinology and genetics. Jonas Salk (1952) developed the first effective polio vaccine, virtually eradicating a disease that had crippled millions worldwide. James Watson and Francis Crick (1953) described the double-helix structure of DNA, a monumental discovery that unlocked the secrets of heredity and laid the foundation for modern molecular biology and genetic engineering.

Organ transplantation became a reality with Joseph Murray (1954), who performed the first successful kidney transplant. This was followed by Christiaan Barnard (1967), who performed the first successful human heart transplant, pushing the boundaries of surgical possibility.

Medical imaging continued to evolve with Godfrey Hounsfield (1971), who developed the Computed Tomography (CT) scan, providing detailed cross-sectional images of the body. Reproductive medicine saw a breakthrough with Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe (1978), who pioneered in-vitro fertilization, leading to the birth of the first test-tube baby.

The fight against infectious diseases faced a new challenge with Luc Montagnier and Robert Gallo (1983), who identified HIV as the cause of AIDS. In molecular biology, Kary Mullis (1985) invented the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), a fundamental technique for amplifying DNA, which became indispensable for genetic research and diagnostics.

Contemporary Period (2000 – 2025)

Genomic Revolution and Advanced Therapies

The 21st century has been marked by an acceleration of medical innovation, driven by advancements in genomics, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence. This period has seen the completion of the Human Genome Project, the development of sophisticated gene-editing tools, and the emergence of highly personalized and targeted therapies.

One of the most significant achievements at the turn of the millennium was the Human Genome Project (2000-2003), which successfully completed the mapping of the entire human genome. This monumental undertaking provided a foundational resource for understanding human biology, identifying disease-causing genes, and developing new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

In the realm of mechanical circulatory support, the First Artificial Heart (AbioCor) (2001) was implanted, marking progress in providing life-sustaining assistance for patients with severe heart failure.

Regenerative medicine took a significant leap forward with Shinya Yamanaka and James Thomson (2006), who independently developed Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs). This breakthrough allowed adult cells to be reprogrammed into an embryonic-like state, offering new avenues for disease modeling, drug discovery, and cell-based therapies without the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells.

Craig Venter (2010) and his team achieved a remarkable feat by creating the first synthetic cell. This demonstrated the ability to design and build biological systems from scratch, opening possibilities for engineering organisms with specific functions, such as producing biofuels or new medicines.

Perhaps one of the most transformative technologies of this era is the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology, developed by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier (2012). This revolutionary tool allows for unprecedented precision in modifying DNA, offering immense potential for correcting genetic defects, treating inherited diseases, and developing new forms of gene therapy.

Advancements in prosthetics and bioelectronics were highlighted by the First Bionic Eye (2013) implantation, which restored partial vision to blind individuals. This technology represents a significant step towards integrating biological systems with artificial devices to overcome sensory impairments.

Immunotherapy, particularly CAR T-cell therapy (2017), gained approval for certain cancers, representing a breakthrough in harnessing the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. This personalized treatment has shown remarkable success in patients with specific hematological malignancies.

The COVID-19 pandemic (2019) spurred an unprecedented global effort in vaccine development, leading to the rapid creation of mRNA vaccines (2020). These vaccines, developed by scientists like Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, showcased a novel and highly effective platform for infectious disease prevention, demonstrating rapid response capabilities to global health crises.

Further demonstrating the therapeutic potential of gene editing, the First CRISPR-edited human (2021) was treated for a genetic disorder, marking a critical milestone in translating gene-editing research into clinical applications.

Finally, the First pig heart transplant into a human (2022) represented a significant step in xenotransplantation. This groundbreaking procedure offers potential solutions for the critical shortage of human organs for transplantation, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in organ replacement therapy.

Conclusion

From the ethical foundations laid by Hippocrates to the genomic revolutions of the 21st century, the journey of medicine is a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance. Physicians and scientists, driven by curiosity and compassion, have continually pushed the boundaries of knowledge, transforming our understanding of health and disease. The inventions and discoveries highlighted in this article represent monumental leaps forward, each building upon the last, to create the sophisticated medical landscape we know today. As we look towards the future, the pace of innovation continues to accelerate, promising even more remarkable advancements in the ongoing quest to improve human health and well-being.

Be First to Comment