Introduction

Peer review is the cornerstone of scholarly communication, acting as a rigorous quality control mechanism in academic and scientific publishing. It involves independent experts—known as “peers”—evaluating a manuscript’s validity, originality, and significance before it is published. This process ensures that research meets high standards of accuracy, reliability, and ethical integrity, fostering trust in the scientific record. In an era of rapid information dissemination, peer review remains essential for distinguishing credible knowledge from misinformation. This article explores its historical evolution, underscores its critical role in advancing science, and provides a practical tutorial for beginners on conducting a peer review.

The History of Peer Review

The concept of peer review has deep roots in the collaborative nature of scholarship, but its formalization as a systematic process in scientific publishing is relatively modern. Contrary to popular myth, it did not begin with the launch of the first scientific journal in 1665. Henry Oldenburg, the editor of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, sought advice from fellows on submissions, but this was informal consultation rather than structured refereeing. The term “peer review” itself was not coined until the 1970s.

Early traces of formal external evaluation emerged in the 18th century. The first documented instance occurred in 1731 with the Medical Essays and Observations published by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, marking the initial use of pre-publication review for medical articles. By 1752, the Royal Society of London established a “Committee on Papers” to vote on abstracts submitted to its Transactions, introducing a ballot-based system without discussion. In the 1760s, the French Académie Royale des Sciences appointed “rapporteurs” to produce written reports on submissions, a practice closer to modern refereeing.

The 19th century saw peer review gain traction within scholarly societies amid the explosion of scientific output. In 1831, William Whewell proposed that Royal Society papers be reviewed by two fellows, with signed reports published in the Proceedings—an idea inspired by French evaluation essays. However, adoption was uneven; commercial journals like Nature relied on editorial judgment alone until the 1970s, when rising submission volumes and specialization necessitated external referees.

World War II catalyzed standardization. Post-war growth in research funding and publications led to widespread formal peer review by the mid-20th century, extending beyond journals to grant allocations. The 1970s marked a tipping point: journals like Cell (launched 1974) made pre-publication review routine, and the term “peer review” entered common usage. Today, it underpins most major journals, though innovations like open and post-publication review challenge traditional models.

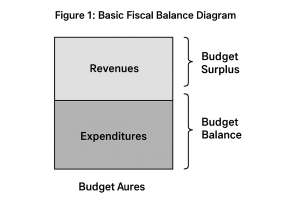

| Milestone | Year | Key Development |

|---|---|---|

| Informal consultation | 1665 | Philosophical Transactions seeks expert advice, but no formal process. |

| First peer-reviewed collection | 1731 | Medical Essays and Observations by Royal Society of Edinburgh. |

| Committee voting system | 1752 | Royal Society of London reviews abstracts via secret ballot. |

| Written reports proposed | 1831 | William Whewell’s suggestion for signed referee reports. |

| Standardization post-WWII | 1940s–1950s | Widespread adoption in journals and funding. |

| Term coined; routine use | 1970s | Nature implements systematic review; term “peer review” emerges. |

This timeline illustrates peer review’s shift from ad hoc advice to a formalized safeguard, driven by the need to manage burgeoning scientific output.

The Importance of Peer Review in Science

Peer review is indispensable for upholding the integrity of scientific knowledge. It serves multiple functions: validating research methods, identifying errors or biases, enhancing clarity and rigor, and ensuring novelty and relevance. By filtering out flawed or fraudulent work, it prevents invalid findings from influencing policy, practice, or future studies—evident in high-profile retractions like the 1998 Wakefield MMR vaccine paper or the 2011 arsenic-based life claims.

Key benefits include:

- Quality Assurance: Reviewers scrutinize methodology for replicability and robustness, catching overlooked flaws or gaps. This elevates manuscripts to the highest standards, with rejection rates often exceeding 50%.

- Credibility and Trust: Peer-reviewed articles signal reliability, essential for evidence-based fields like medicine and policy. Without it, misinformation could proliferate, as seen in non-reviewed preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Advancement of Knowledge: Constructive feedback helps authors refine ideas, fostering innovation. It also exposes reviewers to cutting-edge work, benefiting their own research.

- Ethical Safeguards: It detects plagiarism, conflicts of interest, and ethical lapses, maintaining science’s self-regulating ethos.

Despite criticisms—such as delays, biases, or failure to catch all errors—peer review’s net value is irrefutable. It builds student investment in writing, promotes critical thinking, and ensures diverse perspectives when inclusive practices are prioritized. In a world of open-access and AI-generated content, its role in combating disinformation is more vital than ever.

Peer Review Tutorial for Beginners

Conducting a peer review can feel daunting, especially for novices, but it’s a skill honed through practice and mentorship. As a beginner, view it as an opportunity to contribute to your field while sharpening your analytical abilities. Below is a step-by-step guide based on best practices from publishers like Wiley and Springer Nature.

Step 1: Accept the Invitation Wisely

- Review the abstract to assess fit with your expertise.

- Check for conflicts of interest (e.g., co-authorship, personal relationships).

- Confirm your availability—reviews typically take 1–2 weeks.

- If suitable, accept; otherwise, suggest alternatives.

Step 2: Read Thoroughly

- Skim first: Note overall impression, strengths, and red flags.

- Read deeply: Focus on abstract, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Use resources like PubMed or EQUATOR Network for methodological benchmarks.

Step 3: Evaluate Key Elements

Assess using these criteria:

| Section | What to Check | Common Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Abstract & Introduction | Clarity of aims; novelty; relevance to field | Vague objectives; overstated claims |

| Methods | Replicability; ethical compliance; statistical rigor | Missing details; weak controls |

| Results | Data accuracy; logical presentation | Misleading figures; unsubstantiated stats |

| Discussion | Interpretation; limitations; implications | Overgeneralization; ignored biases |

| Overall | Originality; ethics; language | Plagiarism; conflicts |

- Be objective: Base critiques on evidence, not personal taste.

- Flag suspicions (e.g., plagiarism) without accusing—let editors investigate.

Step 4: Structure Your Report

- Summary: Briefly restate the paper’s aims and findings (1–2 paragraphs).

- Major Comments: 3–5 points on strengths/weaknesses (e.g., “Methods lack power analysis”).

- Minor Comments: Line-by-line suggestions for clarity/grammar.

- Recommendation: Accept, minor/major revisions, or reject—with justification.

- Keep confidential: Avoid sharing manuscript details.

Aim for constructive tone: Balance praise and criticism to motivate authors. A good review is timely, detailed, and fair—qualities that build your reputation as a reviewer.

Tips for Success

- Start small: Review for open-access journals or with a mentor.

- Learn from examples: Study reports from F1000Research.

- Build skills: Join platforms like Publons for recognition and training.

Conclusion

Peer review’s journey from 18th-century committees to today’s global standard reflects science’s commitment to collective scrutiny. Its importance lies not just in gatekeeping but in collaborative improvement, ensuring research withstands the test of time. For beginners, embracing peer review is both a duty and a privilege—start today to strengthen the scholarly ecosystem. As science evolves with digital tools and open models, peer review will adapt, but its core mission endures: advancing reliable knowledge for society.

Be First to Comment